As community development financial institutions work to become anti-racist, it is vital for us to identify and understand the three levels of racism that distort our work. Interpersonal, institutional, and systemic (or structural) racism reinforce behaviors, procedures, policies, conditions, and outcomes that have long harmed our communities.

In 2022, the Biden Administration’s Interagency Task Force on Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity (PAVE) released an action plan. In recent years, a national discussion has spotlighted the role that real estate appraisals play in the racial wealth gap and as barriers to community development projects. Both developments offer CDFIs and other community development stakeholders opportunities for anti-racist interventions to interrupt the myriad harmful outcomes that appraisals have on people of color.

In 2020, a year before PAVE was created, an ABC News segment spotlighted appraisal bias through the experience of Abena and Alex Horton. The couple received a very low home appraisal when Abena Horton, a Black woman, greeted the appraiser alone and the home’s pictures and decor reflected the couple’s multiracial makeup. The couple ordered a second appraisal. This time, Alex, a white man, greeted the appraiser alone. All evidence that he had a Black family was removed from the home. The second appraisal was 40 percent higher.

[Related Article: Getting Beyond Appraisal Bias]

Interpersonal racism, the way personal racial prejudices affect other individuals, is where much of our nation’s discussion about racism is focused. Abena and Alex’s story is not just about one bad actor, however, but is emblematic of how gatekeepers and their institutions perpetuate systemic racism.

Though some appraisers work on their own, others are employed by companies, whose policies, procedures, and practices constitute and perpetuate institutional racism. Whether intentional or not, these practices work to the benefit of white people and harm people of color. With that in mind, what do we know about diversity and inclusion in the appraisal industry?

We know from data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that in 2022, only 4.2 percent of appraisers were Black, 2.7 percent were Asian, and 7.8 percent were Hispanic or Latino. The industry’s professional association, the Appraisal Institute, began a program in 2018 to recruit people of color into the industry. The institute is also providing voluntary unconscious-bias training for its members. In 2021, a number of states, including Minnesota and California, passed legislation requiring appraisers to receive anti-bias and cultural competency training.

We should be alarmed that these measures are coming so late to an industry that is vital to wealth building. And they raise questions about an industry that is primarily self-regulated. We must dig deeper into each company’s policies: Does the company have anti-discrimination training policies? Does it have a review process for the appraisals that its employees conduct to identify outliers? Are outliers tracked based on race to understand patterns? What does the company do when it finds bias or consistent outliers? Institutions set expectations for and regulate their employees and thus have a responsibility to root out bias. Having no practices to systematically identify and limit biased appraisals, let alone a rigorous program to do so, is a manifestation of institutional racism.

Other institutions are highly dependent on appraisals to determine “fair” market value. Financial institutions use appraisals to determine the size of their loans. Banking regulators and GSEs require banks to use appraisals so that they can rate the banks’ safety and soundness and rate mortgage portfolios by perceived credit risk. This determines banks’ interest rates. Do financial institutions have appraisal company standards requiring their appraiser vendors to have anti-bias training and practices to identify value anomalies? Do regulators and GSEs require banks to have such appraiser policies or even inquire about them? If not, each of these institutions is complicit in institutional racism.

Rinse and repeat this cycle thousands of times. When institutions interact in ways that create discriminatory outcomes, we are witnessing systemic racism.

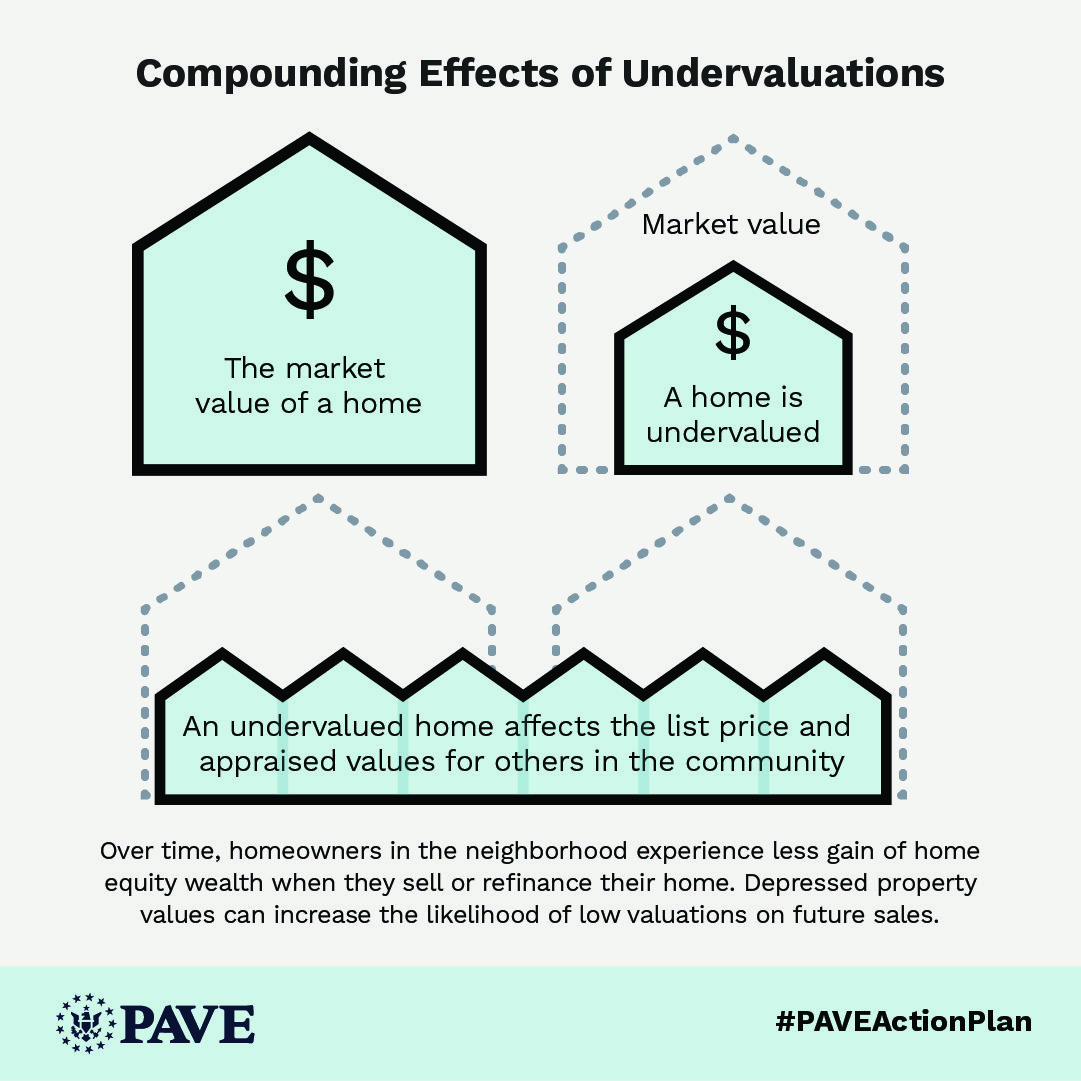

An appraisal that undervalues a home like the Hortons’ becomes a “comp,” or comparable sales price, used in other appraisals as part of the process to set the value of another house in the community. This is systemic racism at its most insidious, as multiple low appraisals devalue communities over time, following a seemingly legitimate process. The outcome is illegitimate, devastates communities of color, and helps perpetuate the racial wealth gap.

Even if all future appraisals could be guaranteed to be free of individual bias, they would still be very much affected by decades of devaluation from legally sanctioned redlining policies. I described those challenges in detail in a previous Shelterforce article.

Community developers confront this reality when working in formerly redlined communities. When they try to help families obtain mortgages for newly constructed housing, the appraised value of the home is often lower than what it cost to build it. The gap must then be paid by the family upfront or covered through government programs. Similarly, community developers are told that rehabilitating distressed or abandoned homes in these neighborhoods would be “over-improving” them because families would be unable to get a mortgage high enough to account for the improvement costs. The family would have to buy the property without the improvements instead, then pay to rehab the house.

Taking Action

Interrupting decades of policies and practices that have caused brutal inequity will take time and requires intentionality. Just as the levels of racism build upon each other, the deconstruction of these structures must be done in stages. Community development professionals and institutions, such as CDFIs and community development corporations, along with our colleagues in the philanthropic sector and local, state, and federal governments, can all be powerful voices in this endeavor. As leaders, we must start with our own institutions and ensure that our staff understand, and actively work against, the institutional and systemic forces that create the racial wealth gap. That starts with challenging every artificially low appraisal and includes advocating to banks and to the government, as described below.

The PAVE Task Force should be applauded for its Action Plan, which outlines governmental actions that are intended to interrupt racism across all three levels. The plan mostly places the burden of reform and prevention of racist devaluations on the appraisal and finance industry and on government institutions. As anti-racist advocates, we—CDFIs, development corporations, and our colleagues—need to strongly support these government actions. There are critical steps we can take now.

PAVE Task Force Action Plan: What We Can Do

Interpersonal Racism

“Require appraisal anti-bias, fair housing, and fair lending training for all appraisers who conduct appraisals for federal programs and work with the appraisal industry to require such trainings for all appraisers.”

We should be asking all appraisal companies if they require anti-bias training for their employees for all mortgages and advocate with our financial partners and investors, like Chase and USBank, that they do the same.

Institutional Racism

“Building a well-trained, accessible, and diverse appraiser workforce” through “lower barriers to entry in the appraiser profession,” and “provide funding opportunities for testing, education, and outreach pertaining to appraisal bias and discrimination.”

The federal government is seeking to provide grants to states initiating training programs, and has already given a grant to this program in Mississippi. We should seek diverse appraisal companies and advocate with our financial partners and investors that they do the same.

“Define metrics that can help to identify and measure patterns of mis-valuation in the property valuation process.”

We should ask appraisal companies whether they have internal control systems to identify and correct misevaluations and advocate with our financial partners and investors that they do the same. For example, whenever a valuation is made that is a certain percent lower or higher than is typical for the neighborhood, particularly for residents of color, there could be a system in place to notify the company.

Systemic Racism

“Develop a legislative proposal that modernizes the governance structure of the appraisal industry” and “strengthen coordination among supervisory and enforcement agencies to identify discrimination in appraisals and other valuation processes.”

There has been pushback from the appraisal and real estate industry on this recommendation, centered on resistance to governmental authority and a belief that the industry can best regulate itself. Of course, the fact that few appraisers are people of color and that the FHFA has already conducted research showing significant appraisal bias belies the notion of self-regulation. We should all be advocating for this collaboration.

“Address potential bias in the use of technology-based valuation tools through rulemaking related to Automated Valuation Models (AVMs).”

It is vitally important that we do not bake structural racism into the powerful technological tools already affecting the finance industry. This is where government regulation should be focused and where we have little influence other than to fully support the PAVE recommendations and accountability.

“Expand regulatory agency examination procedures of mortgage lenders to include identification of patterns of appraisal bias.”

Accountability to closely monitor and eradicate racial bias patterns is vitally important to transition the industry and restore “fair” market value.

The Action Plan also includes several recommendations empowering consumers to file complaints about discriminatory appraisals by making the process to do so easier and more transparent. It is in this area that the federal government has taken significant action to educate consumers on their rights for review and correction. Though important, these types of efforts differ from the previous actions in shifting the burden (knowledge, time, and resources) of undoing the racist acts to the victims and do very little to stop bad “comps” from reverberating throughout the system. Even so, the Justice Department has confirmed that appraisers can be held liable when appraisal discrimination occurs. Such liability may push lenders to more actively require appraisal companies to employ systemic controls.

The PAVE Task Force also made three exploratory recommendations regarding how to interpret and use appraisals that are relevant to our work as community developers:

- Expanded use of alternatives to traditional appraisals as a means of reducing the prevalence and impact of appraisal bias.

- Use of value estimate ranges instead of an exact amount as a means of reducing the impact of racial or ethnic bias in appraisals.

- The potential use of alternatives and modifications to the sales comparison approach that may yield more accurate and equitable home valuation.

Fannie Mae recently announced that traditional appraisals will no longer be its default standard and it will allow alternatives for property valuations. This change has significant implications for community developers and may allow alternative valuation mortgages to have access to the secondary market. CDFIs have always had the ability to originate mortgages with alternative valuation models. In my earlier Shelterforce article, I discuss how my own CDFI, IFF, has never used appraisals to determine community facility loan sizes since its inception 35 years ago. Instead, IFF primarily uses the income approach to determine value. The challenge, of course, is scale. CDFIs have limited balance sheets to originate and hold nonconforming mortgages, and therefore we affect only a tiny part of the market. If the secondary market becomes open for such alternative valuation mortgages, CDFIs will have more ability to make such mortgages. More importantly, CDFIs can demonstrate to the mainstream financial world that these alternative models can combat redlining’s legacy of racist valuation in our communities.

The most promising recommendation is the opportunity to use ranges to set value. CDFIs can add a “restorative justice” credit of some percentage to the value of properties for all loans in under-resourced and formerly redlined communities. Some CDFIs already apply a standard 110 or 125 percent of appraised value to their loan sizes to account for racist devaluation. Often appraisals include value ranges in the notes of the appraisal report, and CDFIs could require appraisers to do so. CDFIs could then lend at the high end of ranges as a standard operating practice. If CDFIs can originate such mortgages for Fannie Mae, there is tremendous opportunity to begin to restore value to our communities. State and local governments could also add restorative justice corrections to grants and soft debt to make up for devaluation.

There is so much work to be done. We cannot only wait for government action; we must also act now. We need to examine our own policies and practices and use our positions on boards, advisory committees, and the power of our deposits at local, state, and national banks to advocate for an examination of their appraisal policies and practices. How would the system change if powerful investors like Chase Bank, Bank of America, and USBank insisted that their appraisal vendors have policies and practices that intentionally provide and require anti-bias training and create institutional systems to proactively identify and correct mis-valuations? Would we see more fair market valuations? After George Floyd’s murder, these institutions expressed solidarity in strong equity statements. Imagine if their policies and practices around appraisals aligned with those statements. A great start was Chase Bank’s $3 million donation to the Appraiser Diversity Initiative to help diversify the industry.

Becoming an anti-racist community development organization requires intentional and deep analysis that goes beyond interpersonal racism and prejudice. CDFIs and community developers are rightly focused on removing the racial wealth gap, but to do so, our work must focus on institutional and systemic racist outcomes of appraisal mis-valuations that perpetuate the deep inequity in our nation’s predominant way of building wealth—homeownership.

This article is greatly indebted to Race Forward’s Different Levels of Racism Framework and the education I received from Crossroads’ Chicago Regional Organizing for Antiracism (Chicago ROAR) program.

Great article! NYMC launched a program in 2021 designed to combat bias in the appraisal industry by training individuals and securing jobs through their lending partners for BIPOC individuals who are interested in entering the field. https://nymc.org/get-involved/appraiser-program.html

The statement that “An appraisal that undervalues a home like the Hortons’ becomes a “comp,” or comparable sales price, used in other appraisals as part of the process to set the value of another house in the community” is misleading. Many of the bias complaints have concerned refinance transactions. The appraised value of a refinanced house NEVER becomes a comparable. Only sales are comparables. In addition, in the case of a sale, the appraiser almost never even meets the buyer. Quite often, the appraiser might not even meet the seller, as most folks are at work during the day, when the appraiser goes to the house. It is very common for a realtor to give the appraiser access to the house. Sometimes, the appraiser does not even meet the realtor. Many appraisers have lockbox keys & the realtor simply provides the lockbox code by phone, email or text. Quite often, the appraiser goes into an empty house & does not even meet anybody involved in the transaction. In addition, the writer describes the appraisal profession as self regulating, which is entirely inaccurate. Appraisers are required to have an appraisal license, issued by the state where they do business. An appraisal license is very difficult to acquire & very easy to lose. State appraisal boards discipline appraisers all the time. An appraiser is required to adhere to ethical practices (defined in USPAP – Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice) & to be technically competent (familiar with professional standards)& to be geographically competent (familiar with the market area). State appraisal boards can & do take disciplinary actions against an appraiser for violations of any of those standards. The disciplinary actions can include requirements for additional appraisal education, fines, license suspensions & license revocations. Unless I’m missing something, this state regulation is hardly self regulating. By the way, I am an Hispanic woman & I have been an appraiser for 46 years.