Shelterforce’s investigative reporter Shelby R. King wrote two pieces about YIMBY (Yes in My Back Yard) groups in 2022, including one that focused on shared interests between YIMBY supporters and housing justice organizers.

The article raised a question: could tenant organizers work together with YIMBY groups, despite the latter’s tendency to overlook tenants’ push for key rights like rent control?

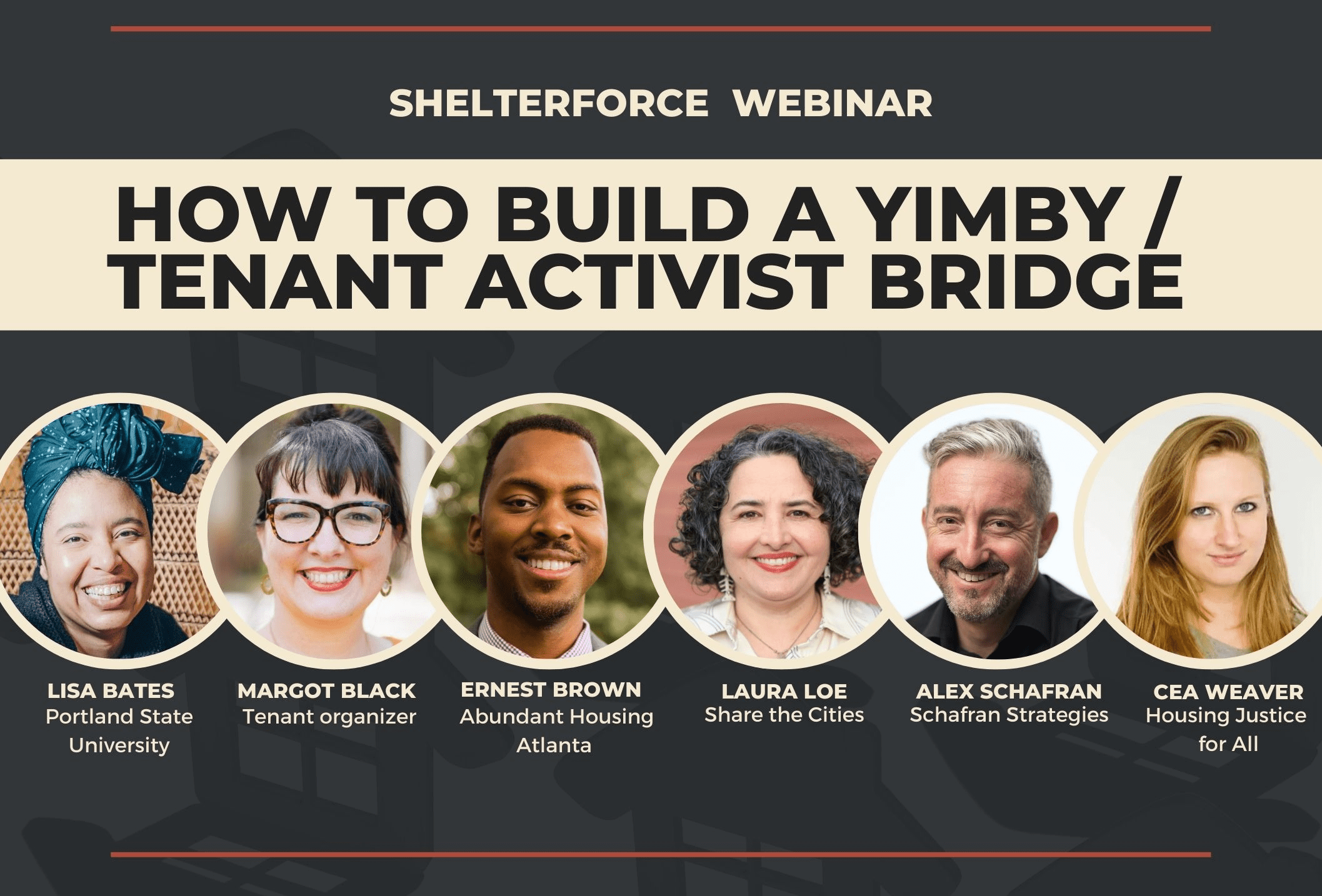

King recently moderated a webinar, How to Build a YIMBY/Tenant Activist Bridge, about this search for common ground. The following speakers attended:

- Lisa Bates, professor at Portland State University in the Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning and in Black Studies

- Margot Black, tenants rights organizer, activist, advocate, and founder of Portland Tenants United

- Ernest Brown, executive director of Abundant Housing Atlanta

- Laura Loe, founder of Share the Cities

- Alex Schafran, housing consultant for Schafran Strategies

- Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator for Housing Justice for All

The following is a lightly edited account of the webinar. Watch the full webinar above.

Shelby R. King: I wrote a series of stories recently that discussed the relationship between YIMBYs and tenant organizers. We got a whole lot of feedback and a whole lot of interest, and we really want to have this conversation to focus on moving forward and on the possibilities for cooperation, and hopefully collaboration, between YIMBYs and tenant activists. But we also think it’s really important that we acknowledge that part of the reason we’re having this discussion, and that this discussion is necessary, is because there have been some hurtful and some harmful interactions between groups, between people from both sides of the groups, and we want to make sure that we acknowledge that and that those interactions are not dismissed. They have caused real harm and we need to sit with that, but then also hopefully try and move forward.

I would like to offer you guys the time to introduce yourselves, and then provide a couple examples that to you illustrate the current state of the relationship between tenant organizers or housing justice folks and YIMBYs.

Cea Weaver

Cea Weaver: I am the coordinator of Housing Justice for All, which is a statewide coalition of about 80 grassroots tenant organizations and organizations that represent homeless New Yorkers in New York State. We have worked across the state of New York to build a people power movement that is capable of challenging the role that the real estate industry plays in our state capital, Albany, New York.

Our primary focus for many years has been on strengthening and expanding our state’s rent control system. So, we were tremendously successful in 2019 in strengthening that system, and rent control is a top priority of the organization. Our second priority for our organization, though, is more housing for low income and homeless New Yorkers.

So we’ve had some success on that front, including passing a statewide bill and winning money to convert vacant and distressed hotels into permanent housing. But we’ve had maybe less success on the front of building truly affordable housing for New Yorkers, though as an organization that does represent people who are currently unhoused, the question of creating housing opportunities for people who currently don’t have them is at the forefront of our minds in Housing Justice for All. I’m happy to be on this panel but I don’t like to use the word YIMBY.

In New York City where I am based most of the time, a lot of people don’t even have backyards anyway. And I think the sort of isms—YIMBYism, NIMBYism, whatever—have become so triggering for so many people and have captured too much attention, when really what we’re trying to talk about here is what kind of housing are we building and where, and who is going to have power over what that housing is going to look like. I think power is really central to the type of conversation that we’re having.

When we are building more housing, is that entrenching and cementing the too-much power that many of my members feel the real estate industry has over their lives? Or when we’re building more housing, is that creating housing opportunity for people who are shut out of the housing market? Is it creating a pathway to collective control over land and housing as a resource and a source of power?

So, when I’m thinking about the current state of play between people who want to build more housing and people who are organizers in the tenant movement, I’m really thinking about what are people’s different definitions of power? And what do people think that the best path forward is in order to address a problem that I agree with the YIMBY movement on, which is that there are way too many people in New York state who don’t have homes, and who don’t have affordable homes, and are not stably housed.

Can you explain your thoughts on how the relationship between YIMBYs and tenant organizers got where it is?

Ernest Brown

Ernest Brown: I’m currently here based in Atlanta, Georgia, which is where I’m from, but I spent five years in the Bay Area, which is where I got active in the founding of the Bay Area YIMBY movement.

I’m on the board of YIMBY Action, the 501(c)(4) that’s been very active over the last several years in advocacy around local and statewide housing issues in California, and increasingly has become a national organization over the last few years. I also just joined the board of Yes In My Backyard or YIMBY, an affiliated 501(c)(3) that does a lot of impact litigation and other research work around the housing issue but does not engage in politics, given the (c)(3)–(c)(4) lines so I can speak as an institutional actor, in both of those lenses if helpful.

But to this question, I’ll give both an Oakland and an Atlanta example here. I’ll do the Atlanta one first because I think it’s really interesting in this conversation, the dynamic of a blue city and a red state, which is true a lot of your Sun Belt metros, so your Texases, your Floridas, your North Carolinas, where a lot of people are moving to and the power structure, such as it is, that we were just talking about is really one of not caring a lot about tenants.

Georgia prohibits any form of rental regulation or anything that seems like it might be rental regulation. I heard that the state of Tennessee preempted the city of Nashville from regulating Airbnbs. There’s been similar types of state efforts to preempt anything that might seem like progressive local legislation on housing issues.

So the power dynamics of both YIMBYs, who are trying to change power to unlock more housing, and tenant actors, who are trying to change legislation to unlock more regulations on rentals, are actually quite aligned and facing a not-accommodative state apparatus. And trying to figure out how can cities be creative with the powers they do have to unlock opportunities for both renters and aspiring homeowners in the communities that are seeing a lot of population growth. Essentially every one of your fast-growing metros is in that Sun Belt area. So the problems of abundance and sharing enough are very present here in Atlanta and elsewhere in the Southeast.

But I will give a couple of California examples. I think a more recent one is the California Social Housing Bill, which has been a bill that the YIMBY chapters I know are supporting actively in California. And I can speak to my time when I was in Oakland; we actually invited the Oakland tenants union to come meet at a space we had and to get at what were the resources we had, as abundant housing activists, to try to share and make more fruitful those relationships at a local level. So I’ve seen some positive movement there, but I think it’s become more structured over time . . . at least the movement I’m affiliated with, it’s become more institutionalized over time.

Laura Loe

Laura Loe: I founded Share the Cities first as an organizing collective, then I was Patreon-funded and then two nonprofits to address kind of a holistic vision for both King County in Washington and connecting with mostly YIMBY organizations across the U.S. and beyond. I went to the first YIMBYtown. I spoke at the second YIMBYtown on what I considered to be a critique of the YIMBY movement. My talk is on YouTube, it was about intersectional urbanism and what that meant to me. , it was about intersectional urbanism and what that meant to me.

I was born in Bogota, Colombia. I’ve done a lot of different past organizing experience around immigrant rights issues in Chicago and housing and food justice work when I first moved to Seattle. I’m a renter. I moved here in 2009 and Share the Cities is basically a group that can mobilize for other people.

We get tapped by tons and tons and tons—at this point, hundreds of organizations every week, it seems like—to mobilize our folks, who show up. They show up to testify, they show up to mutual aid, they show up to stop sweeps, they show up to do electoral work. An organization can kind of borrow our people power for their movement building. A lot of the folks in Share the Cities have a lot of privilege. And so a lot of the work I do is around making sure that folks show up to organizing spaces and do less harm. I really see what I do as civic matchmaking, but I have been very instrumental since the beginning of being involved in the YIMBY stuff, including YIMBYtown in Portland most recently.

It’s very complicated. I have a very complicated relationship at this point. I say that YIMBY for us is a verb. It’s part of many of the things that we’re doing, like public broadband advocacy and other work. It’s just part of making a city better. And that YIMBY is a land use reform shortcut. It’s a term. But on the internet, on Twitter, I’ve been very involved in the housing discourse on Twitter, which is why I think I ended up here today.

You ended up here today partially because of the cooperation aspect and what you just said about the way that Share the Cities has focused on really building that bridge.

Margot, you are the last official responder to this question. Can you talk a little about the state of the situation in Portland?

Margot Black

Margot Black: I founded Portland Tenants United, which aspired to be a citywide tenants union, essentially using the labor organizing model to leverage our collective power to pay rent or withhold paying rent to effect changes in policy, or through building-based organizing to renegotiate our leases or otherwise change the material conditions that we’re living under and challenge power. [We] have enjoyed a lot of pretty exciting successes since starting that organization, including the 2018 statewide passage of statewide rent control. I’m going to put it in quotes because it’s a little too high to really be called rent control, 7 percent plus inflation, but a rent stabilization policy.

And we also were kind of the main architects of passing a relocation ordinance in the city of Portland that pays renters who are displaced through rent increases that they can’t afford or no-cause evictions a substantial amount of money to offset the very real costs of moving. And I bring up that work and the founding in 2015 to highlight that that really happened at the same time as what would become Portland’s YIMBY movement. And when I came into this work—I am a renter then and still, and certainly probably forever, and a mother, and a single mother. There was a lot of stress in that time about rents going up and who was to blame and a lot of different ideas about how to create a more livable city

I came into this as a math professor. And so I had the STEM background that I applied to this problem. And so I personally was able to see that with more people moving to the city, we do need more bodies, but we have to make sure that the people who were here first can still live here and still enjoy the city that they helped build, that they raised their babies in. They want to make sure that their babies can move back here and help take care of them. And that’s really my North Star, that everybody deserves housing that is both secure and dignified. And that the vision is that anybody can find housing that is affordable, quality, dignified, that they can stay in—afford and stay in—in perpetuity in the community that they need and want to be in. And that’s what really guides my work. And I realize I didn’t even talk about the YIMBY stuff.

I’m going to ask the question next of Lisa, who is also in Portland. When we spoke last week, you talked specifically about how Portland has been able to avoid some of the conflicts that we hear about often in the Bay Area or in New York City. And you talked a lot about how housing justice folks and YIMBY folks were able to come together in Portland. I would love if you would talk to us some about avoiding some of the conflict and some of the cooperation options that you’ve seen.

Lisa Bates

Lisa Bates: Of course in Portland, we’re very “nice,” read passive aggressive. So the conflict, as hot as it gets, is still pretty lukewarm. But really I would go back way further than just this kind of recent YIMBYism. Time travel isn’t available to everyone on the call, but Oregon has a 40-year-plus history of a state land use planning system that one of its goals requires that all jurisdictions plan for needed housing at a diversity of types, locations, and meeting the financial capabilities of all Oregonians. That doesn’t solve the problem, but it has avoided some of the worst, most hardened NIMBY exclusionary land use policies and practices. We also have urban growth boundaries.

So in the Portland metro area in particular, land use, environment, climate advocacy folks have always also been connected to the question of housing. Really because the urban growth boundary, the densification of the city, the transit planning is probably most threatened by a fake affordable housing argument. It really is not about people who care about housing affordability. It’s driven by home builders who want to build green fields from here to eternity because it’s easy for them to do so. And so there’s always been a connection—long before YIMBY—of folks in that movement, in the land use planning who are very connected, not only to housing availability, but through groups like Housing Land Advocates (HLA), very strongly to enforcing the real meaning of Goal 10, that it’s a diversity of housing for all income groups and fair housing. So they’ve always also been talking about race and racial exclusion, which obviously happens everywhere in the country, but there’s some special history in Oregon around racialized exclusion.

So HLA and also organizations like 1000 Friends of Oregon have been fighting for regional fair share housing. They fought for a long time to get rid of the state preemptions on inclusionary zoning and 1000 Friends of Oregon incubated both the organization that ultimately has become the ADPDX, the Anti-Displacement Portland Coalition, and Portland: Neighbors Welcome, which is probably the most organized abundant housing supply group. organized abundant housing supply group.

I actually don’t think they say “YIMBY” very often, maybe because of some of the tensions around that label that other folks have mentioned. But being incubated in that same space there was a dialogue from the beginning such that I think Portland: Neighbors Welcome, you’ll see them focusing their attention on historically exclusionary areas of the city and the Metro area more so than historically disinvested areas.

You will see them showing up for anti-displacement provisions in the residential infill rezoning and upzoning in the city. They have showed up for tenant protections. They have shown up on tenant screening, on just cause evictions. And they have also led on investigating some of the racialized dimensions of housing exclusion in the city. They will put forward concept plans for turning the golf course in the rich neighborhood into a housing development.

They’ve just really focused their spatial advocacy around a different place. And I think that contextually, because Portland’s kind of an old-school growth machine city, there are some guys, you could name their names, who control the land and do the development and own stuff and go in the back rooms with the cigars. It’s actually really easy here to see “the market” not working. It’s really easy to see how the market does not supply abundant housing routinely.

That’s actually Econ 101. When prices go down, we stop bringing things to the market because there’s some tangencies and marginal costs and marginal revenues there. And so I think it’s been easier to see some of the common problem and understand that the supply of housing, the abundance of housing, the diversity of housing is interlinked with racialized exclusion, is interlinked with disinvestment over time, and cannot be resolved by pooh-poohing the idea of displacement. It has to be a conversation that happens all at once. And I think this longer history, but then this deeper history, is really important, but this immediate moment and space in which climate, land use, environment, housing, and equity have formed on the same crucible is really part of that ongoing collaboration.

Laura, Margot, Cea, Ernest, and folks who are on the ground, does any of that ring a bell for something that you see that is going on for cooperation in your area, or is what Lisa is saying bringing up any opportunities that you see that could be new in your area?

Laura Loe: There’s so many in everybody’s stories here that echo my personal story, as well as our city stories. Both the growth boundary in Washington state, the Growth Management Act, really informs our conversation at a state level and kind of helps everyone, even if we don’t agree on— There’s this idea of concentrating growth to protect wild lands. That’s a shared value in Washington state that reminds me of what goes on in Portland and that helps for unity.

And then the fact that Washington state has such abysmal, such horrific tenant laws, so in favor of landlords and property owners; some of the worst-, least-protected tenants in the U.S. are in Washington state. And that really does create a place where even some market-leaning folks are like, yeah, these renters are really vulnerable, we need some sort of stabilization. And so things are so bad that we’re not fighting as much in the nuanced areas in those two places. And then also I was a math teacher, so there was a lot I related to there.

Margot Black: I just wanted to underline what Lisa had said about the YIMBY groups in Portland that in particular testified in favor of tenant protections, both locally and at the state level, including our rent stabilization policy. I think that that has been a very, very important component of the YIMBY and tenants rights groups having a partnership … mutual support of causes.

And to address what somebody has brought up in the chat about whether or not tenant groups and YIMBYs, for lack of a better word, could, say, agree to disagree on rent control and agree on everything else. Absolutely not. As long as we can also agree to disagree on supply. That’s really core to a tenants rights activist’s toolkit for housing security and anti-displacement. It’s not the only one. And certainly the conversations are very nuanced, but what has been so successful about Portland’s tenants rights movements and the YIMBYs is that they haven’t disagreed on that. It hasn’t always been an easy conversation. And I will say that the YIMBYs do, if pushed, they’ll often break for the developers or break for the Econ 101 teachers who think that rent control will lead to the end of the world.

But in general, that was a really, really important part of building trust and showing, when you can get a group who you believe is led, either secretly or not, by greedy developers, to come in and testify in favor of what at the time was considered a very radical policy, it’s a really, really big deal. And if those two groups can’t agree on that, I don’t see how we can ask for abundant housing and all get on board with that while we also agree that we are going to savagely push people out of their homes and communities as soon as somebody else can pay a higher price. We don’t apply perfect market principles to home ownership, and I don’t know why we would apply it to renters. And I think that we need to ground our housing work in making sure that people can stay in their communities and enjoy the benefits of housing stability because that’s when we free up the energy to work on all the other stuff and build our communities back.

Ernest Brown: This notion of the growth machine has also been really fascinating to see with new eyes upon getting back to Atlanta. And it’s very much that similar dynamic of, there’s a handful of almost exclusively old white guys—although they’ve diversified it a little bit—in Atlanta, who are driving the major development projects in Atlanta. And they tend to be quite problematic, both from like what we’re talking about here, but also a basic tax policy standpoint that tend to often get heavily subsidized from government. A recent book, Red Hot City, by a professor at Georgia State, [is] sort of a chronicle of how we’re just giving away hundreds of millions of dollars every year in very needed public tax revenue to support stadiums and other kinds of mega developments.

But one exciting thing I really liked about coming back to Atlanta is because it’s not such a highly procedural process to build any amount of housing, there’s still an industry of people who build duplexes and town homes and other kinds of small homes with missing middle housing. And that’s actually been a really useful agreement point that, well, that’s not what’s ruining the notion of a neighborhood and that’s not what is causing massive displacement that’s happening in parts of Atlanta. It’s really this other thing that’s happening. And so how do we reorient the development trajectory of Atlanta to be less massive scale blockbusting, sort of urban renewal 2.0, into this more neighborhood-scale development that can actually be led by members of our neighborhood? Because that actually has a much more diverse developer, financier class behind that model development. So that’s been a helpful alignment point here in Atlanta.

Cea Weaver: So in New York state right now, our governor is pushing for the statewide plan to encourage cities and municipalities and towns, particularly along our regional rail system out of New York City—so we’re talking the city, the suburbs, and the cities immediately surrounding New York City—to increase their residential density. And Kathy Hochul’s zoning plan encourages municipalities to upzone. These are already extremely high-cost neighborhoods, right? So it’s not a plan that is particularly leading to more low-income housing or affordable housing. And it’s not a plan that is leading with tenant protections or housing affordability whatsoever. is leading with tenant protections or housing affordability whatsoever.

And it’s presenting this opportunity for the nascent YIMBY movement in New York state to lobby on behalf of this plan, to sort of take on . . . some of the most exclusionary places in the country. We’re talking Nassau County, Westchester County, where places have been suing to block multifamily housing development for decades and decades and decades. So it’s interesting to see what’s going to happen there.

These are conservative places that typically don’t vote for Democratic leadership in Albany. So it’s going to be interesting to see what happens as this nascent YIMBY movement tries to bring some of those things across the finish line at the state level. At the same time, we are pushing very hard for tenant protections and rental assistance to be a part of this conversation. And we are threading a line that basically says, we’re not trying to stop this zoning plan, but we think it’s not going to work for anyone at all to produce any housing, especially for the people who need it most, unless it has rental assistance and tenant protections included. So we’ll see what happens and where this goes. And if there’s opportunity for collaboration here at all, I think it’s sort of early to say.

I spoke recently with Shanti Singh, who is the legislative coordinator for Tenants Together in California. And she said that during the last round of negotiations for the social housing bill, there were some really positive conversations around getting some of the asks that tenants rights folks had into that bill. I know that the social housing bill didn’t move forward last time, but I realize it’s probably not dead in the water. I’m sure we haven’t heard the last of it. Where do you see opportunities moving forward, if it isn’t reintroduced, or if there are other affordable housing bills in California, where are you seeing some opportunities for collaboration there? , or if there are other affordable housing bills in California, where are you seeing some opportunities for collaboration there?

Alex Schafran: Since we are starting with the question of who gets credit, just want to first shout out you all, Shelby and Miriam and all the team Shelterforce for having the courage to write about this topic, to put this on. I know some people are thinking maybe there’s going to be some shouting when we come on here today. I just really appreciate it. It’s super important, the coverage that you’re giving of these conversations, and folks trying to make peace here and find ways to work together really actually helps move that forward. You’re having a really productive impact on the housing conversation, I think. And I think that’s really important, and I hope other journalists are paying attention to what that means. And I think that’s one thing everybody on this panel shares, is an interest in just this conversation that we’ve been having has to produce better housing, especially for lower-income folks. And so I just appreciate that productivity. Also happy to be mentioned in the same breath as Shanti Singh.

Shout out to Shanti. That’s a person who’s been sweating blood for decades for these things. And so I try to be helpful where I can, but I don’t deserve nearly the same credit.

Speaking from the California space . . . I’m a former academic and longtime observer of these things and writer about these things. I guess I still am a writer. Now I’m a consultant, so I’m actively working in coalition building. And I’m now a member of Ernest’s old organization, East Bay for Everyone. I’m also a member of East Bay Housing Organizations, which is sort of a center of the housing justice movement here in the East Bay. I identify as a houser hardcore and I’m an “all housing, all the time” person. And I’ve been thinking about this and trying to figure out ways in which there can be peace.

You mentioned one which gives me a lot of hope, which is the push around social housing. We had an amazing run last California legislative session. This year, it’s going to be interesting. I don’t want to sort of sully the waters. Tune in in six months and we can talk about California Social Housing 2023. One of the things they just talked about was this was a bill that was led by the YIMBY organizations, or some of them. Again, East Bay for Everyone, Derek Sagehorn—shout out as a really key intellectual and political force and energy force behind this.

We never got to the point where we were able to get the bill authors and sponsors—again, I was not part of it—never got to the point where we could get the equity groups on. There’s a lot of backroom conversations. But I don’t view the sort of not getting there as a sign that we’re not going to get there. It was just so many conversations that just had never been had before. We’re talking about a crazy huge plan for social housing in California that would have been unthinkable five years ago. The fact that these conversations are even happening is a wonderful sign. It died not because of this in any way, hardcore serious old school legislative politics, some of which had nothing to do with housing, were what ultimately saw this piece die. And again, as we move forward, I’m confident that we’ll be able to get there.

It’s hard and sometimes activists on the YIMBY side or in the tenants rights side think that they’re the only people in the room, or act as if. But again, in this case, for instance, a lot of the affordable housing developers also didn’t get there. And some of them who’ve had a really hard time becoming tenant advocates; slowly but surely, they’re moving. My own organization, East Bay Housing Organization, that I am proudly part of, took a very, very long time in its history to become pro tenant. And that’s something that I know is sad—a little shout out to the recently departed Gloria Bruce who, again, sweat blood for years to be able to get her organization on the right side.

So there’s so many people in housing. It’s wonderful to hear people talk about the growth machine, which is a great book about the complexities of urban politics and how it relates to growth. And I think we’re starting to see both tenants rights and YIMBY activists take a more complex and nuanced and complete perspective on this massive system we have that either does or does not build the housing that we desperately need. Again, social housing is one of them. I could use the rest of the hour talking about other areas of collaboration, but we’ll start with that.

Speaking of social housing and protections, Laura, you’ve got the Seattle social housing bill working its way through. Can you talk about any tenant protections that are written into that, how collaboration happened, if it did, and what sort of steps you took to facilitate that? steps you took to facilitate that?

Laura Loe: I don’t think in Seattle, the shared enemies between what I’m going to call from now on urbanists who are basically our YIMBYs, and the left, which could be called FIMBY. . . I’d say that our shared enemies aren’t just big developers or big property management companies that do predatory investment and are predatory on renters. But another shared enemy we have is NIMBY homeowners who, in community councils and chambers of commerce, want homeless sweeps and cops, when we know that neither of those help get people into housing.

So in Seattle, there’s a broad agreement among the most active, loudest urbanists and the folks on the left that maybe were involved in the uprising, occupation of CHOP CHAZ [Capitol Hill Occupation Protest/Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone], that then faced a backlash from the conservative downtown chamber interest in Seattle that put forward their own ballot initiative, that we all worked together to get to fail. Which is really exciting that it did fail—over a legal challenge, but we were going to make sure it also failed if it went to the ballot. And then out of that no came the yes. I was not directly involved.

But back to my role as a civic matchmaker and making sure that the folks that have more maybe educational privilege or wealth privilege or different privileges could show up in solidarity with most impacted communities. Someone reached out to me after that failed and said, you know, I really want to do a progressive tax thing. Is that something Share the Cities can do? And I was like, let’s find out what the folks that have been on the ground the most fighting this push for more carceral solutions for homelessness and all of this nonsense…let’s see what they’re going to come up with.

And so out of that grew a really deep partnership between a lot of the social justice urbanists and folks at Real Change, who then worked with their Real Change vendors—[Real Change] is a street newspaper—and other partners, really wonderful Black leaders in Seattle and many other folks, to come up with the social housing initiative I-135. We are today—it’s really exciting, I hope all of you will follow along—we are seven days out from the election. The election is next Tuesday, we’ll find out whether Seattle has a social housing developer in the tenant protections in it.

It goes back to I think it was Margot or Cea’s point about power. This is really a conversation about power and the power imbalances in our electoral systems and then just our day-to-day systems. But this really tries to get at that power imbalance with a tenant-led board, union built, and then any new buildings, not the buildings that would get acquired by the developer, which is another path that they could take, but any new buildings would also be passive house green standard. So this brought climate justice on board, unions on board, you’ve got mainstream Dem orgs all on board, you’ve got teachers associations, you’ve got—pretty much everybody supports this.

I would say that the very, very, very small, quiet, soft little “no” that’s come out is around the fact that this goes up to 120 percent area median income, which in Seattle, for a family of four is around $144,000. So there are some voices that are like, “Oh, this takes the focus off of under 50 percent AMI or under 80 percent AMI.” But other than that, we’ve pretty much had unanimous support. There’s been a few people asking questions. But what I would say in terms of that grassroots—getting rid of that kind of YIMBY, FIMBY Twitter housing war piece that goes on—I would say, this gave us all something to grow in the same direction, to fight against the same interest. Everybody knows that once this gets built, there’ll be a fight around where to site it. And that 75 percent of the land in Seattle is off limits to new multifamily housing. So there’s just no disagreement among folks on the left in Seattle.

Someone who’s a big unifier on this, I want to give a shout out to, is Shaun Scott in Seattle DSA, who . . . when he was running for city council, really emphasized exclusionary zoning. You’re not going to build new social housing in the wealthiest community like Laurelhurst in Seattle without rezones, and you’re not going to be able to place the social housing near some of the most beautiful parks in Seattle without rezones. And so that that rezoning piece is just a tool to make sure there is that geographic equity.

I could go on for a really long time. But the folks at Real Change work with vendors. The majority tenant board I would say is the most powerful thing. And there’s nothing—I can’t say this enough to all of the developers in Seattle, all the nonprofit housing folks and the PDAs that already exist in Seattle—there’s nothing stopping them right now from putting a majority tenant board together. There’s nothing stopping them, and this should inspire them, regardless of what happens next Tuesday.

So that makes me curious. Cea and Margot, as tenant organizers, in listening to the talk about the social housing bill and some of the projections that are in there—what sort of provisions would you need to see for your group or you personally to come out in active support of a social housing bill?

Cea Weaver: Let me just talk about how we’re talking about social housing in New York; maybe that will answer the question. Social housing for us is housing that is democratically controlled by residents, it’s eco-modified and permanently affordable and protected from the private market, and it’s public. And we’re sort of using it both as an umbrella—an umbrella term maybe is the wrong phrase, but we really rely on the community service society’s definition of social housing, which really treats it like more of a spectrum, like “this is social housing, and this isn’t.” Housing can be more or less social; public housing is social housing in some ways, because it is fully decommodified, fully public. It’s also really over-policed and residents don’t feel like they have strong decision making over what’s happening in public housing.

So there are ways in which public housing is really social and ways in which it isn’t. And so we kind of are using it as a way to evaluate certain types of housing that currently exist and analyze certain types of housing on sort of a matrix or a spectrum. And that’s been a really useful tool. Because we don’t really want to be in a fight about … something that barely even exists in the U.S.

And then the second thing I will say is that we are drafting our approach to social housing legislation in New York. We’re trying to figure it out. It’s a state authority that is capable of expropriating existing housing. A huge thing that is coming up for us in the social housing conversation here is that so many of our members live in substandard housing, owned by slumlords. And we really feel as though a really good faith thing that the social housing YIMBY-style organizers can do is support a housing plan that leads with providing tools for residents of existing rental housing to take control of their homes and to transfer those homes into the public sector.

So we’re leading at that sort of expropriation angle. The second thing is that housing is poor quality too. And sometimes people want to live in brand new housing, right? And so our social housing authority, we are envisioning that it is going to be able to build new housing, particularly in some of the slower-growing parts of New York state where the market just isn’t going to be able to do it. So we’re talking to tenants in Utica, we’re talking to tenants in Rochester, and in these places where maybe there’s less housing demand or YIMBY organizing wouldn’t necessarily go, right? Because the demand isn’t there. The economies are slow, but people live in substandard housing that they don’t want to live in. They want new housing too.

Our social housing authority must be able to address that with deep rental subsidies and the ability to build in those places. Additionally, it has to be able to address building housing in high-cost neighborhoods where the market is producing housing that people can’t afford. So we are really talking about social housing as something that is, because it’s run by the state, flexible enough to meet really different types of markets, which a zoning-only social housing plan can’t really do. Something that’s capable of building state capacity and something that can lead with helping people get better homes right now.

And then the last thing that I will just say about social housing is we are not starry-eyed about what we think we can get the New York state government to do. And we are sort of situating this in a long-term power-building strategy to take control of our state government through people. And so, I am here in my 501(c)(3) capacity, but we are closely aligned with organizations like the DSA and the Working Families Party that are explicitly taking on housing as a core electoral issue and running candidates who want to build state capacity for housing. And the social housing authority also would have the power to override local zoning, but that’s not what we need to lead with, because zoning isn’t the core of the issue here.

Margot, did that resonate with you as far as what it would take to support a social housing bill? And can you weigh in on your thoughts there and then maybe some of what you have going on in Portland, some of the issues that you’re working on getting legislation or new regulations passed to increase tenant protections?

Margot Black: Yeah, really I have hardly anything to add to what Cea said because she was so thorough and I’m just ready to move to New York and study her and get involved with everything you’re doing.

But I agree kind of the outset on just getting it defined. I’m a tiny bit out of the game on the advocacy circuit. And so the social housing phenom of the last couple of years is new to me. I just think about public housing, which is kind of sort of the same but different, but really just decommodified housing, first and foremost. And as Cea mentioned, democratically run. I mean, whoever’s living in that housing needs to have power and agency over their housing and in their community. And so I support all supply initiatives that move toward a goal of essentially nationalizing our housing supply would be the goal. But anything in between where we are now and there, I think for tenants rights movement to support, you really do want to see tenant protections built in. I would say as a renter who was radicalized by my own lived experience of no-cause evictions and unaffordable rent increases, and then working with folks in the trenches who are dealing with what I dealt with, but a thousand times worse because of additional barriers and lower incomes and whatnot.

Tenants who do have any capacity to do any kind of organizing while being crushed by the gears of capitalism, have a really hard time getting super excited about long term supply initiatives. Like we’re just not going to door-knock for affordable housing bonds and for inclusionary zoning and for supply initiatives that are going to come down the road in 10 years, not because we don’t believe in them, not because that isn’t what we need and want, but because the situations we’re dealing with are so acute right now that what is going to get folks to call their legislators or knock on doors or go out into the streets are things like rent control and ending no-cause evictions or application fees and screening and application barriers. And things that are really affecting our ability to just get by day to day and know where we’re going to live from one month to the next.

And so it’s just it’s just been my experience that it’s hard to activate renters on supply-driven stuff en masse.

That is a good segue to touch on what I’ve seen [in] a few chat questions. Where are the shared goals? What can we get tenant organizers to door-knock for? And what do tenant organizers need to see YIMBYs show up to door-knock for? A question that has come up for me a lot is in a power dynamic—what can we agree on? What can we support each other in? And then who makes the first move?

Ernest Brown: I want to just try the question in reverse a little bit, because we have heard it framed the other way. Is there any expectation that YIMBY should expect to see some sort of commitment from tenant organizers before they would be willing to enter into coalition? It’s just the other way around. I can see the heads nodding. And I just want to name that that’s an expectation.

Margot Black: Well, I wouldn’t say that. I mean, I’ve been asked to testify as a tenants rights organizer, we’ve been asked to support movements, but it’s usually been an exchange.

Ernest Brown: I mean, was my question clear?

Margot Black: I think so. Do YIMBYs need tenants to door-knock for us? Or is it the other way around? And who comes first?

Ernest Brown: Right. But I guess I was hearing a little bit of a question in what Shelby was saying of what the tenant organizers need to see from YIMBYs to believe that they are about this coalition. And I was trying to just reverse the question, but swap the nouns, what the YIMBYs need to see from tenant organizers to believe that they’re about this coalition? Or is that a fair question? That’s sort of what I was asking. And I was interpreting the nodding in a different direction like YIMBYs don’t get to ask that question. They should just be ready for the coalition, and they should be grateful to receive it.

Ernest, I don’t think anything is an unallowed question. But I do think that that question comes up if YIMBYs are in a position of power and we have talked about oftentimes newer, especially YIMBY groups tend to be upwardly mobile, often white. They have seats at the city council table, they get listened to more often. And so with that sort of automatic power, does there come a place where it falls to YIMBYs to show up first because they have that sort of power? And I think another thing that has come up in this research is, are tenant activists willing to accept that help when YIMBYs show up, and they show up sincerely? And what needs to happen to show tenant organizers that YIMBYs are sincere?

I would love to hear what tenant organizers need to see from YIMBYs to accept the help that I hear over and over from folks that I interviewed for these stories, folks who are in abundant housing groups, say very much to me, we want to help, we want to help. I would love to hear what help needs to be illustrated.

Ernest Brown: And I think that the point of me framing that question was to try to get at this notion of, it’s a little difficult to ask for coalition, but kind of demand that the other partner always be the junior partners of the coalition, but also they’re the powerful ones. It’s a difficult notion of coalition building as it’s sort of like the price YIMBYs must pay to enter the coalition is to accept all of the tenant organizers’ values, positions, and prioritizations. And therefore they get to be in a coalition in which maybe they will see their priorities advance, maybe, but only after they’ve achieved the other ones. That’s what I’ve seen historically be one of the compounding factors to sort of building it as a coalition versus getting YIMBYs to sign on to the tenant organizer program. Does that make sense?

In the case in Atlanta, neither of us are getting what we want. And so there’s a very clear sense of, we will be stronger together, and maybe some of the things we want will come to pass. But I think [of] some, particularly West Coast, cities, where tenant organizers have a long history of winning things, and earning rent control in San Francisco, earning it in Oakland. And so then in that situation, to treat the YIMBYs as the one with the power, when the individual YIMBYs, the YIMBY groups that I was a part of and founded were not the rich developers who designed the current land use regime; they were the ones who were trying to change the land use regime. So they didn’t perceive themselves as powerful even if their broader social class may put them in some sense, a relatively stronger sense, but the tenants union had staff. The early YIMBY movements had no staff. So just when you were thinking about who has the power here and who is being asked to give or accept, just those dynamics I think were a little more complicated.

I definitely agree. The dynamics in the whole situation are complicated, which is why we are having our conversation.

Cea Weaver: Yeah. I think that power is a bizarre concept and difficult. I do want to just push back slightly on the framing of what’s happening in California and tenant organizations have staff and won rent control, so they have power and YIMBYs don’t have staff and the land use regime is what they’re trying to change. I think it’s just more complicated than that. When I think about power, and I know you know it’s more complicated than that. Just for the sake of oversimplifying for this conversation. YIMBYism to me, I mean, people have been asking me this question a lot, what do you make of all the new YIMBY groups in New York, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Like it’s this new thing that our governor is pushing housing, and there’s YIMBY groups now, and blah, blah, blah, blah. I don’t think it’s actually a new thing. It’s really about supply and demand, it’s a fundamental sort of philosophy behind our whole economic system and property ownership and building more housing as a way to sort of solve the housing crisis is fundamental to the entire approach to how we’re solving the housing crisis.

And tenants are trying to do something different. They’re trying to say, actually we’re permanent renters. Actually we need stability in our homes, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I see where people who want more housing and want more rental housing can think about how to build together. I also can see how it’s frustrating. I do think though that that sort of analysis, tenants have political access and therefore power and YIMBYs don’t, isn’t accurate to how power shows up in these conversations. I think in terms of building a coalition, I don’t think that solidarity means that, okay, YIMBYs carry our agenda and we carry YIMBYs agenda. That’s not going to work.

I would maybe just take a huge step back and be like, what are the shared values here? Can we work on something new together? Maybe that’s a social housing bill. I don’t know. I think that sort of framing that I’m going to fight for zoning changes if Open New York or YIMBY groups supports good cause eviction. That’s really not where we’re trying to go and it’s not solidaristic. And so I don’t know, I’d like to maybe start thinking about where we align and maybe we can work on one thing together that is on both of our agendas as opposed to, we’re carrying each other’s work.

And so going off of that, what are some of the shared goals?

Lisa Bates: I have a different question about this premise, which is why are these two completely separate people? Why is this dichotomized in that there’s one kind of person and another kind of person and they never the twain shall meet?

As we were talking about the webinar prep I revealed that I do not participate in Twitter. It makes my life nice in a lot of ways. And one of the key ways is that it’s possible for me on an individual basis to get in a room and have a conversation with people around housing that is not primarily shaped by an online conversation. And I genuinely worry that there is a conflation between a very real and serious analysis about power and politics and the way that stuff shows up in a really unproductive online space. Because we have to have a really serious conversation about power and the real politics, material politics of what’s going on. And we do not have to have that in the terms that people fight about with each other on Twitter. When I see the spaces that come together in Portland around anti-displacement and broadly defined YIMBY, some characteristics are that the people who are interested in that collaborative space who primarily come to it on the supply side are not all white, all upper middle-class background, all high income, all wanting a gentrification aesthetic.

It’s a broader set of people who are able to speak to desires and hopes and dreams about living in cities and being in space with other people in a way that looks a lot more like many of the people who are renters and tenants who I do think care a lot actually about development and how development happens because most of the people that I work with are very concerned with spatialized displacement and the history of urban renewal and the practices of “revitalization planning.”

But the conversation has to start from people recognizing that we do not live in an Econ 101 world. So if you are a YIMBY and you don’t want to be a jerk, you cannot show up and just yell at people that more supply is good for everyone and no one ever gets hurt, because that’s not true. It’s empirically not true. And if you insist that you know exactly what will happen on any one particular development or development on the large scale and that there will never be any consequences, but great things for everyone, you say you don’t know a lot of Econ, but also you don’t know a lot of reality and you don’t know how to talk to other people.

I would say, in general, I’ve seen that dynamic happen more than the other way around. And I think that’s why the framing ends up being, what does YIMBY have to let go of, because I do see those being the stompy feet that come into the spaces. But again, I think that making our movements not be exclusive to only a certain kind of demographic and a certain kind of vibe and communication style is a big start in how we develop a real coalitional politics that also can acknowledge that sometimes all the interests are not shared.

Alex Schafran: I would like to agree with Lisa. And [add] just a few things that I think are really important. Back to Ernest’s question of what are the reasonable expectations that both different groups of people, again, many of whom are like me, either members of both organizations or who are both renters. (I’m not a renter, but I am a member of both organizations and a huge believer in tenants rights. I’m also a believer in all forms of housing tenure, including home ownership and community control and resident control.) So I think there is a reasonable [expectation] that you can accept the brutality of the history of these issues in the United States, and particularly the ways that it has devastated people of color, low-income people, whole neighborhoods. This is just history, and it is true. And so if you’re rolling in with kind of an ideological perspective that denies so much of this history and that doesn’t accept, again, some of the reasons why some of these zoning rules which should be changed were put in place in the first place, isn’t just pure NIMBYism by upper middle class folks, it’s because of damage that was caused by the real estate industry doing things in a different era.

So I think some basic acceptance is important. I do think it’s important to acknowledge Margot’s point earlier, that yes, there may be renters in both groups and I’m a member of both groups, but the income and the power, some of which is racial-related, is different often in different groups.

Can you expect somebody to be advocating for the things that are just necessary for your basic survival first? Support me in my basic survival so that I can be present and be here to work with you on these long-term visions. And I think yes, that’s an explanation that folks have. And so again, one of the things that gives me hope about what I see with some of better of the YIMBY groups in California is that they’re not trying to exchange support and rent protections as a quid pro quo for something else. It’s like this is fundamental. I was happy to see Ernest, Laura, and YIMBY action groups issuing a statement on the Biden rental protection plan saying that’s great, but it needs to be stronger, and linking to a National Low Income Housing Coalition brief on how it could be better. That didn’t feel quid pro quo. That felt like, yes, we’re saying that we’re here.

And the other day, I was in a meeting with a bunch of regional advocates on rent regulation. And there were YIMBYs in the room. And I heard somebody who was definitely not a YIMBY, and who’s long been a housing justice warrior, somebody very skeptical of the real estate industry and of YIMBYs, talking about how he appreciated he’s really seeing in this housing element process we have in California, where each jurisdiction has to make a housing plan, really seeing folks show up from the YIMBY movement to really help build better housing policy at the local level and ensure that not just zoning reform is in there and new units, but also tenant protections in other forms..

So I think that kind of just showing up, that can’t be quid pro quo. I would add as a final point [that] what I think is happening a little bit in California is that you are starting to see some grassroots interaction with folks. And one thing that I would love to see dropped is this idea that YIMBYs are not also a grassroots group in many cases. Sure, they may have donors and there’s various people and people may be in the real estate industry, but there’s a lot of folks out there grinding hard, regular folks, just like in the tenants rights movement. And that’s something that’s really important. And that’s a myth that needs to sort of go away and die. Both are very grassroots. And because both are actually very grassroots, neither are powerful. We talked about the growth machines. If you dig into how power actually works in the real estate industry and the housing industry in California, neither group has enough power to realize its big visions.

That is something that I think both groups at times are struggling, right? There are certain folks within the YIMBY voice who say, “Hey, we’re winning. We don’t need to build coalition with these equity folks. We’re winning, we’re winning, we’re winning.” When in fact, I don’t think that they’re quite winning yet. On the equity side, somebody recently asked me, do we need a bigger tent? And the answer was no, we need to leave the tent. Equity at times can seal itself within a tent space based on people who see everything like them and are risking at times isolating themselves from power. It’s not a way of building power, it’s a way of isolating yourself from power. And I think there is a slight mentality shift that needs to happen.

And again, I’m hoping that in some ways if both YIMBY and equity and housing justice folks can be more OK making peace with the fact that none of us are particularly powerful. Like I’m parts of all kinds of non-powerful groups. And if we want power, if we want influence, we’re going to have to do some really scary stuff and that’s where it starts to get really hard. And we’re all going to have to kind of step out of our comfort zone. But I do think you can ask for that basic acknowledgment of the history of the injustice, of how bad the situation is and of the power imbalances within our organizations as a place to begin.

Laura Loe: In terms of the reciprocity and the transactional organizing piece. A market bro flew me down to meet Sonja Trauss in 2016 and this person wanted me to be the next Sonja Trauss and start a Seattle YIMBY group and all of this stuff. And I flew down and met Sonja and spent quite a long time talking with her at the time. I just felt like there was a different path forward for me because of already the work that I was involved with, housing justice work and Tent City Collective and the tenants union and other things that I was doing. I was like, I just don’t think that I can start a YIMBY group. I don’t really feel like YIMBY is a noun for me. I don’t really want it to be a noun for other people. And I really, like I’ve said, especially recently, I always say YIMBY for me is a verb and I’ll show up to YIMBY against design review. I’ll show up to YIMBY against historic districts. I’ll show up to YIMBY and get other people to YIMBY while they’re doing other things. But I really reject it as a noun and identity.

And I talked to a lot of folks ahead of this meeting about what do they think of the YIMBY, what is YIMBY in Seattle? And all the people that kind of said to me, they were confused when they first moved to Seattle and they had done land use reform organizing and pro-housing organizing in other cities. And they showed up and they’re like, where’s the YIMBY group? Where are the YIMBYs? How do I find them? And then they realized that there’s actually hundreds and hundreds of grass roots and grass tops. And there’s some developer shill ones and there’s some struggling-just-to-pay-for-food-for-a-meeting ones. And we actually have so many YIMBY groups, and it’s just embedded in their full platform of different things they’re working on. And I think that’s a strength in Seattle and Washington state.

I heard a lot of abundant housing and YIMBY groups talk about expanding their platforms over the last several years. And I wrote about the added nuance to YIMBY platforms.

Is there a space for cooperation on some goals without requiring everyone to sign on to hot button topics like supporting rent control? Lisa mentioned that there’s space for coalition without having to agree on every single thing. And so speaking to the hot button issues, Margot, you said no, we can’t support YIMBY groups if YIMBYs can’t support rent control. Would somebody like to weigh in on the possibility of forming a coalition on the points that do make sense for both sides and just kind of letting the things that we don’t have shared goals on stay on the wayside? Is that a possibility and how? Cea, if you could, is rent control just such an important issue that without that support, you couldn’t support any YIMBY things? I’d love to hear from someone on the possibility of getting some of what we want, but not all.

Cea Weaver: This quid pro quo way of talking about it isn’t that useful from my perspective because rent control is our top priority and we’re going to work on rent control because that’s what our base of members needs and wants. And we want to build a coalition around rent control, we’re not going to walk away from that demand in order to build with YIMBYs. That being said, I think that there’s tons of people who maybe identify as YIMBYs who would benefit from rent control and who want it and we welcome them into our movement. Whenever anyone endorses our rent control work, we are thrilled. And when, and if, we’re in a different position in rent control, we win it or it’s not our top priority, then we can talk about building a coalition or working on something sort of explicitly with the YIMBY organization.

But I think the framing isn’t that useful because I’m not asking YIMBYs to stop working on what they’re working on. I don’t think they’re asking me to stop working on what HJ4A is working on. So to me, I’m not trying to negotiate on the terms of what our demands are. I think that maybe there’s going to be a land use fight where we could work together because the housing is truly affordable, or some other sort of terrain is going to emerge where we need to fight together. But I don’t see walking away from rent control as a demand in order to build a coalition as what we’re about right now, if that makes sense. And I don’t know if that fully answers the question, but yeah, rent control is necessary from our perspective, and it’s always going to be necessary. And real estate and rental assistance is also necessary, and we’re aligned with the real estate industry in thinking that rental assistance is necessary. I would think about it that way.

Ernest Brown: Two things. One, I think the element of time that someone mentioned earlier is really important. All the land use changes that are quite important to the YIMBY movement, those are 10-plus year shifts we’re trying to create. None of those are going to save somebody’s house from getting torn down tomorrow unless you implement demolition controls and things like that. And we often talk in Atlanta about, we’re not going to ask someone who’s facing imminent eviction to come to this land use planning meeting that’s about a small-area plan that will be implemented in the next year’s five-year comprehensive planning process. That’s not the ask here, right? So I just want to state that.

Coming back to this question of well, what can we work on then? Again, we have the “gift” in the South of, rent control was just not realistically on the scale as long as Republicans have a vice grip on the state legislature and have gerrymandered themselves into a decade of control of our legislature regardless of who wins how many votes in an election. It’s not an active sort of thing to potentially split the coalitions. But what is, is how much money do we have so that the city can go around and buy up dilapidated apartment buildings, rent stabilize them or, because they own them, they can rent stabilize them and also make renovations. That’s been a very big issue here in Atlanta. We’re seeing a lot of speculative investment in lower quality housing stock in the historically Black parts of the city. And the money to go get that is a tax policy measure. And that’s a thing we’ve been able to work hand in glove with our local tenants rights activists at Housing Justice League about how do we unlock hundreds of millions of dollars of local money that can be used to advance the aims, to our right to counsel or a more proactive acquisition strategy.

And that in no way contravenes any YIMBY notions of abundance to know some people believe rent control has some issues, in some way by not having that to become the be-all and end-all of are we for, are we against; we’re actually able to find a lot more positives on ways to work together on other parts of the issue.

Margot Black: As a renter, the whole first several years of my organizing, when you talked about the rent being too high, you’d hear from the landlords and everybody else that we just need more supply. And that gets very frustrating as a renter to hear that that is the solution and that rent control isn’t. And I think that is where at least I get so sensitive when I hear, can we agree to disagree on that? Because those are my landlords who are telling me that I just need to wait for more supply to come online, and then my rent will somehow magically go down even though it’s only gone up. That’s where that sensitivity comes from, I think … if all you’ve been told is that supply is the answer when you’re experiencing something so different, it’s really hard to trust the YIMBYs who aren’t pro rent control.

Thank you.

My name dorenda I live in the shelter and I was wondering how I can get an apartment from housing connect. I have applied for apartment and never get picked. I thought that shelter people have 5% preferred. How can my housing specialist help me with that?