On most days you’ll find Eloisa selling empanadas and fresh fruit such as coconut and lychee from her food cart.

She works near the corner of 14th and Irving streets in Washington, D.C., a bustling area in the diverse Columbia Heights neighborhood where you’ll find a thriving community of street vendors selling a variety of goods—homemade foods, clothing, flowers, and even art. The area gets heavy foot traffic thanks in part to the nearby DC USA mall and the Columbia Heights Metro station, one of the city’s busiest.

But informal street vending in the area began long before the station opened in 1999. Street vending has long been, and will continue to be, a vital source of survival for low-income families who live in the city. And it’s helped folks preserve their cultural traditions. Columbia Heights is a longtime home to immigrant households from across South and Central America, and a large population of Black residents.

Eloisa, who moved to the States from Venezuela in the late 1980s, has been a food vendor in Columbia Heights for four years. Vending has helped her find purpose and opportunity, she says, and she enjoys working in one of D.C.’s liveliest spaces.

A street vendor in front of DC USA Columbia Heights Shopping Mall along 14th at Irving Street, NW, Washington, D.C., January 2022. Photo by Flickr user Elvert Barnes, CC BY-SA 2.0

But being part of the informal economy has led to a lot of stress and worry for street vendors, who live in constant fear of criminalization. Many of the 50 or so vendors who typically sell around Columbia Heights operate without a city license, which vendors say is difficult and expensive to obtain. Police have often used sweeps to force vendors to leave the area, arrest them (vending without a license is punishable with up to 90 days in prison), or enact a post-and-forfeit procedure, which gives vendors 15 days to pay a fine at a police station. Vendors must often make an impossible choice between earning survival income or facing an arrest or fine for vending without a license, while also maintaining physical safety.

But informal vendors are not taking their displacement lightly. They’ve begun working together as part of Vendors United DC, or Vendedores Unidos, a group of more than 50 Black, Latinx, and Indigenous vendors who are organizing to fight police harassment and improve working conditions.

“Before Vendedores Unidos, the police were very rude, very nasty,” Eloisa says. “We’re not selling drugs, we’re selling food to people passing by, but they don’t see that.”

Santiaga is one of the vendor worker-owners of the Vendors United Food Co-op. She keeps alive an indigenous food tradition passed along to her by her parents from Guatemala. Photo courtesy of Megan Felix Macaraeg, Beloved Community Incubator

Another organization—Beloved Community Incubator—is working in collaboration with residents in multiple D.C. neighborhoods to create self-organized support structures to resist the criminalization of informal street commerce. The organization’s goals are twofold: to create a pathway toward the decriminalization and legalization of food sales, and the transformation of street vending from an economic activity of last resort to a career that allows people to thrive. Building vendor power, a trend that’s also seen recent tangible victories in New York and California, is a critical tool for reimagining how urban economies can serve the most marginalized, while eliminating the uncertainty and violence that these communities face.

“Where there are vendors, there are hubs of the community and hotspots of conflict, not just interpersonal conflict, but also with the convergence of new, whiter, wealthier residents, and longstanding Black and brown residents that have used that street corner for non-monetized uses for generations,” says Yannik Omictin, an organizer with Beloved Community Incubator.

The influx of more affluent and more white residents over the last two decades has led to increased police presence in the area, Omictin says. And that has had a disproportionate impact on Black and brown vendors. Data from the D.C. Sentencing Commission on vending offenses from January 2018 through September 2022 reveal that 95.4 percent of vendor arrests during that timeframe were of sellers of color, according to Beloved Community Incubator.

Barriers to Legal Vending

Vendors say the onerous steps required to obtain a D.C. vending license have made that pathway almost impossible to attain. At 83 pages long, and published only in English, the rules and regulations to obtain a vending license creates barriers to legal vending: all vendors are required to get a permit for a specific site or for mobile selling, complete Department of Health certification, and shell out more than $2,000 to obtain a license. Vendors pursuing a license who have previously been convicted for selling without a license are barred from access and are offered no restorative pathway to the legal approach unless they can commit an estimated $2,000 in startup fees, which goes up to $7,000 if they want to sell downtown. The complicated processes are reflected in the decline in permits granted by the D.C. Department of Consumer & Regulatory Affairs, which fell from 370 permits in 2014 to just 17 in 2019, according to a report by Vendedores Unidos and Beloved Community Incubator.

The barriers to becoming a legal vendor leave sellers exposed to steady, low-level harassment that can unexpectedly become swift, violent crackdowns by police. A galvanizing moment among D.C. vendors occurred in November 2019 when police accosted 15-year-old Genesis Lemus and her 10-year-old brother, who were selling plantain chips and atole de elote, a drink made from corn, while their mother Ana ran errands. After threatening to send the children to the Department of Children and Family Services, the police placed Genesis in handcuffs and threw her to the ground, with a police officer injuring Genesis’s knee during the arrest. This moment, one of countless harsh encounters with city police, prompted an upsurge in anger among residents and vendors, pushing sellers to organize, which eventually led to the creation of Vendors United. (As Genesis went to testify at a Metropolitan Police Department oversight hearing in February 2022 about her experience, she learned that the police were harassing her mother in that moment.)

At first, Vendors United coalesced as an informal union, a tool to resolve conflict between vendors, as well as to create collective structures to respond to police incursions. Given how burdensome it is for vendors to comply with city regulations, creating a sense of solidarity was a critical first step to making deeper changes. BCI technical assistance director Geoff Gilbert says that the city needs to meet vendors where they’re at by minimizing the steps required for legal compliance, in ways that respects their working conditions.

“It’s not coming from a place of not wanting to be in compliance with the street vending laws, but vendors are not able to comply with the laws right now because there’s basically no support from the city,” Gilbert says. “The laws are written in a way that’s not informed by the lives of street vendors at all, when it could be focusing on the workplace safety conditions of street vendors.”

As the informal union was gaining steam, vendors’ lives were drastically transformed by the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. As informal workers, many of them undocumented, few had access to federal unemployment resources that saved other workers from calamity. With street activity also curtailed, a customer base large enough to sustain sellers dwindled rapidly.

One vendor who experienced significant hardship during the pandemic was Rasul El-Amin, who is Black and Indigenous. El-Amin sells self-designed clothes, oils, and other goods. While he received small support from various nonprofit organizations and mutual aid groups that raised funds for contingent workers, he was still selling homemade masks in the early pandemic, all while living in a shelter. D.C.’s City Council allocated $61 million to support a campaign by the Excluded Workers Coalition, a fraction of the $200 million they requested, and El-Amin says he feels that vendors were forgotten while emergency resources were distributed during that early COVID period. Recognizing the great need the community faced, Beloved Community Incubator and Vendors United collaborated on multiple fronts. First, nearly $100,000 was raised for vendors who were locked out of formal relief channels in the pandemic’s opening months. Beloved Community Incubator and other organizations also raised money to pay food vendors for the free meals they provided at weekly mutual aid events. In time, this created multiple hubs of vendor activity around the city, strengthening community ties in the process.

Finally, in February 2022, Vendors United and Beloved Community Incubator launched a collaborative effort called Vendors United Food Cooperative, a worker cooperative owned by 16 Caribbean and Central and South American food vendors. This was the first attempt to formalize a new model for food sellers to have access to more consistent, up-front money.

“When we organize with the vendors, we say co-op, we say ‘solidarity economy,’” Gilbert says. “But for people to be able to feel what that means and give meaningful consent to whether they want to do that and take on the responsibility of becoming an owner of something, we felt the best way to do that was to do an experiment.”

The co-op began offering a weekly one-meal subscription service for local residents at $20 per meal for eight weeks. Buy-in from residents exceeded the co-op’s goal—about 150 residents bought subscriptions, and meals were picked up at a local park, which organizers hoped would protect vendors from police harassment, although a nearby neighbor still called the police. The initiative allowed vendors to have more upfront funds available to them. The cooperative continues today, offering training to vendors to strengthen their long-term success.

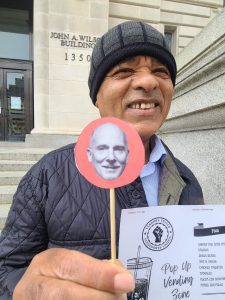

Street vendor Kahssay Ghebrebrhan holds up a picture of D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson at a protest at the municipal office building. Photo courtesy Megan Felix Macaraeg, Beloved Community Incubator

As it builds economic sustainability through these collaborative efforts, Beloved Community Incubator is also pushing two legislative reforms in the D.C. City Council. The first—the Street Vending Decriminalization Amendment Act—would remove criminal penalties from unlicensed vending, reducing the consequences to a small (but still undecided) fine, with a greater emphasis on education for vendors. Going further, the Sidewalk Vending Zones Amendment Act would create zones around the city, including 1 in Columbia Heights (which will contain more than 50 sites) where licensed street vendors could make sales. The measure would also waive any unpaid civil citations, retroactively up to five years, for anyone who receives a license. This is a critical tool for bringing sellers into compliance, says Gilbert. Individual vendor licenses would be available, and the measure would also create a sidewalk manager license for street vendor cooperatives. (BCI plans to to support vendors to create their own organization to apply for the license.)

In November, D.C.’s City Council hosted a public hearing on the Street Vending Decriminalization Amendment Act and the Sidewalk Vending Zones Amendment Act, and vendors were allowed to share testimony. Although D.C.’s City Council adopted the language of the decriminalization act into the Revised Criminal Code act of 2021, the language won’t be in effect until October 2025 without further action from legislators. With more than 100 people present at the public hearing, vendors told legislators “Ni Un Año Más,” or “Not Another Year,” before they see the legal reforms they need.

A Shift Across the Country

D.C.’s potential legal reforms mirror similar developments in other jurisdictions, while pointing to the challenges associated with simply reforming laws around vending. One major victory for street vendors occurred with the September 2022 passage of SB 972 in California, which legalizes access to local health permits, which were previously only available to brick-and-mortar food vendors. The campaign to support street food sale began in Los Angeles in 2009 and has moved through various stages of the approval process since then. Los Angeles County first decriminalized the sale of street food in 2017, and then legalized its sale at the beginning of 2019, but did not formally issue permits until January 2020. (It’s also worth noting that a lawsuit was filed against the city of Los Angeles in December challenging the city’s “no-vending zones.” Read the lawsuit.) As this shifting regulatory environment shows, challenges remain for the street vending movement across various jurisdictions, as organizers are compelled to determine the best pathway to support sellers while remaining mindful of the health and safety needs of communities being served, especially those buying cooked meals.

Reporting from Next City demonstrates just how critical food vending has been in Los Angeles, and suggests its wider significance as a survival mechanism for countless people, as well as a vital mechanism for creating more inclusive, community-centered economies. With more than 50,000 vendors in Los Angeles generating more than $500 million in annual revenue, street vending has a clear economic impact wherever it is found. Even more importantly, food vendors keep things local: with 70 percent of supplies purchased from local stores, according to research by UCLA urban planning graduate students.

At the same time, effectively implementing policies to support food vendors is not as easy as simply legalizing sales, with the same regulatory headaches that D.C. vendors face present in Los Angeles as well. Despite issuing its first vending permits in 2020, Los Angeles had issued only 165 permits by August 2021, according to a report from Public Counsel, which provides pro bono legal services across the country. An estimated 10,000 eligible vendors have not been permitted, some because they weren’t approved, and some because city outreach to current vendors has been inadequate. The report found that the price to go the legal route would be $10,000 in startup costs and $5,000 in annual fees, completely eating up the $15,000 average income food vendors earn in a year. The result, the report argues, is a de facto ban on legal vending, while further entrenching disparities now that legal vending is theoretically available for sellers to access, something that the campaigners for SB 972 worked to address in their approach to policymaking.

“It was so important for our campaign to invert the traditional model that we see, where policies are made in the halls of power and then applied to local communities with a lot of harm,” says Doug Smith, director of policy and coalition building for Public Counsel. “Vendors worked to invert this model by developing the solutions to the problem from their perspectives and their expertise, and then bringing that policy framework to the legislature with a movement of organized workers.”

Looking to the Past to Help the Future

The critical role of informal vending runs deep in Washington, D.C.’s history as a vital tool for marginalized people to fight for their freedom. That was true for Alethia Browning Tanner and Sophia Browning Bell, two Black women who purchased freedom for themselves and 25 family members and friends by selling produce downtown in the early 1800s.

And the history of vending in the city shows that efforts like Vendors United are not new. For instance, in the mid-1980s, after a sharp crackdown on vendors through heightened regulations, more than 200 sellers worked with Local 82 of the Service Employees International Union, making D.C. the first city to see street vendors pursue unionization. While the vendors had some success resisting government restrictions through this effort, legal vending nevertheless plummeted, from 5,300 licenses in 1984 to just 1,594 licenses after the reforms. Legal vending has only grown more challenging ever since.

Across this longer history, key themes have remained critical. As Kwasi Abdul Jalil, a vendor involved in the unionization effort in the 80s, described it, “We are businesspeople but we are also laborers.”

To create space for street vendors to thrive in D.C., and in other cities across the country, requires a wholesale revolution of the economy that better recognizes people’s right to live and work in their communities, free from harassment. Vendors are fighting not for survival wages and ineffective legal reforms, but to thrive through the hard work they put in each day.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated:

- How much D.C.’s City Council allocated toward a campaign by the Excluded Workers Coalition. It was $61 million.

- During the weekly one-meal subscription service, vendors did not cook food in a licensed partner site as originally reported. They cooked in their own homes.

- The Sidewalk Vending Zones Amendment Act would create 1 zone where licensed retailers can sell their goods, not 6 as originally reported.

- The Sidewalk Vending Zones Amendment Act specifically references cooperatives of street vendors that can apply for the sidewalk manager license. The plan is for Beloved Community Indicator to support vendors to create their own organization to apply for the license, not for BCI to apply for the license as originally reported.

Also, a point of clarification—the cost to obtain a license is more than $2,000, far beyond the minimum of $300 as originally reported.

Shelterforce apologizes for the errors.

Comments