This article is part of the Under the Lens series

An investigation by a United States House of Representatives subcommittee has revealed that despite the COVID-19 eviction moratorium, corporate landlords still evicted tenants and did so at three times the rates previously recorded in public data. Additionally, even though rents were already rising, tenants of corporate landlords frequently faced even higher rent hikes. These findings follow a record-setting quarter when investors bought over 90,000 U.S. homes. By 2021 at least five companies owned over 30,000 single-family homes across the country, while American Homes 4 Rent, Invitation Homes, and Progress Residential each owned over 50,000.

Most coverage of corporate landlords has scrutinized their behavior toward tenants. Rightly so. A 2016 study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that corporate landlords in the Atlanta area evicted tenants at rates far higher than typical mom and pop landlords did. Stories going back to 2019 from The Atlantic and The New York Times have reported on how corporate landlords wait out tenant maintenance requests or divert them into unending rabbit holes of bureaucracy. One 2022 paper from the University of California uncovered how a major profit strategy for corporate landlords has been to saddle tenants with a litany of atypical charges and fees in addition to rent hikes.

[RELATED: Homes or Cash Cows? An Under the Lens series]

Though these stories might suggest that such predatory activity toward renters represents a novel phenomenon, unsavory and large-scale investor landlordship is by no means a new development in Black neighborhoods. As Christine Jang-Trettien, a housing scholar and author of a forthcoming book on speculative investment in Black Baltimore neighborhoods, points out, landlords have bought homes at mass scale in undervalued Black neighborhoods for at least decades now, and a good deal of them have exploited tenants for just as long.

What has made this wave of activity novel has been corporate landlords’ willingness to encroach on what might have formerly been middle-class and mostly homeowning neighborhoods—many of them predominantly Black, but not all of them—and their transparent backing by major investment funds. Institutional investment into single-family homes came to the fore through mass purchases of homes foreclosed upon during the Great Recession, a crisis that disproportionately impacted Black homeowners and neighborhoods. And now, as Congressional subcommittee data shows, corporate landlords are purchasing homes in neighborhoods where the percentage of Black residents is over three times their level of representation in the U.S., where home prices are cheaper than in average neighborhoods, where average rents are conversely higher than in average neighborhoods, and where levels of homeownership are actually higher than in most neighborhoods across the country.

Put bluntly, corporate landlords are turning a profit off segregation. They are buying homes historically devalued because of their location in Black neighborhoods, gobbling them up with little competition due to racial discrepancies in home lending and appraisals and wealth-based inequalities fueled by the massive racial homeownership gap. Their business model is both enabled by segregation and will continue to exploit housing market inequalities without segregation’s redress. As the inventory of starter and entry-level homes available for purchase in the U.S. continues to contract, corporate landlords have aggressively cornered what remains of this disappearing but vitally affordable segment of the housing market. This comes at the greatest cost to Black rental households looking to potentially transition to homeownership so that they can build housing-based wealth for future generations, but affects all households looking to transition to affordable homeownership, too.

Merriam-Webster defines “redress” as “to set right or remedy.” The Redress Movement, where we serve as researchers, focuses on highlighting how the ongoing legacy of segregation impacts communities of color at the local level in order to remedy it. Below, we profile how corporate investors have profited from segregation in two initial cities where our organization has worked—Charlotte, North Carolina; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin—to illustrate the need for redress. We hope these case studies will inspire redress for the effects of corporate landlordship and the legacy of segregation that empowers it nationwide.

Bo McMillan explores: Charlotte’s Residential Investors Buy Up Corridors of Opportunity

Charlotte is now perhaps second only to the city of Atlanta when it comes to the amount of institutional investment into single-family rental homes. According to a recent Washington Post story, 25 percent of its total home purchases in 2021 were by investors. Another recent investigative series jointly published by the Charlotte Observer and Raleigh-based News & Observer found that corporate landlords now own roughly 25,000 homes in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg area. They control 1 of every 20 single-family homes in the county.

For proof that these institutional investors are targeting previously undervalued Black neighborhoods, one need look no further than how their patterns of investment align with Charlotte’s Corridors of Opportunity. These six designated “corridors” represent a key initiative the city has taken on to correct for how a history of segregation led to systemic underinvestment in Black neighborhoods, especially in the North and West sides. According to the city’s own website, the corridors “[serve] as links that connect people to the resources and businesses they need to live and thrive,” and are supposed to leverage public investment along with private dollars to foster communities “where families can grow strong and build legacies for the future.” Whether the people of color in those communities today will get to remain in them to build those legacies, however, is unclear due to marked increases in investor home purchases.

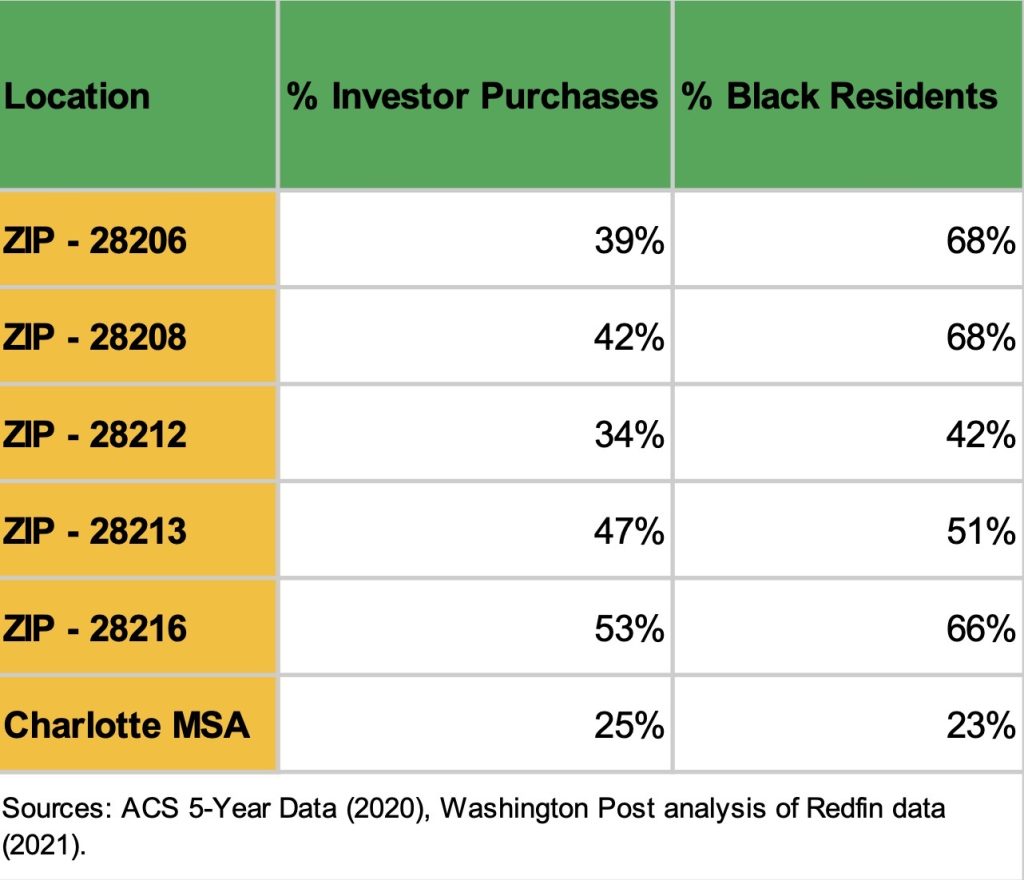

Data shows that the five ZIP codes that correlate to Charlotte’s six Corridors of Opportunity stand out for disproportionately high populations of Black residents and median Black household incomes that are lower than the Black median household income of the Charlotte metropolitan area—$47,090, which already lags behind the median white household income in Charlotte by over $28,000. They also stand out for their concentrations of investor purchases. Investor purchases in ZIP codes corresponding to Corridors of Opportunity exceeded the overall rate of investor purchases in the Charlotte area by at least 9 percentage points in 2021. In the 28216 ZIP code, investors purchased more than half of all homes sold that year.

Of course, The Washington Post data cited above can be only used as a rough proxy to estimate corporate investor activity in these ZIP codes—it does not distinguish between individual investors and corporate investors—but news stories confirm these landlords’ outsized presence in predominantly Black areas such as Hidden Valley (28213) and Peachtree Road (28216). Outside of the Corridors of Opportunity, corporate investors have also drawn the ire of Black residents in other parts of Mecklenburg County such as Potter’s Glen, a historically Black community located in the town of Huntersville and centered around a former Rosenwald School.

Apryl Lewis, a housing justice organizer for Action NC, has seen firsthand how corporate investors have negatively impacted Black homeownership in Charlotte during their recent buying spree. She’s also seen firsthand their locally documented issues with tenants, such as neglected maintenance requests and high tenant fees. Prior to the pandemic, Lewis said, Action NC partnered with Self-Help Credit Union and local real estate firms to help low-to-moderate-income tenants and tenants of color in Charlotte build credit, develop financial literacy, and transition into affordable homeownership. Since the pandemic, however, the number of these programs they can fill with clients and run has dropped by at least half.

Even when they do offer classes, Lewis said, “those same programs now are basically obsolete [at the point of home buying] because corporate landlords can come in and they don’t have to wait for funding.” Low-to-moderate income households, and especially households of color, tend not to have the liquid capital available to compete with the types of high-cash offers corporate landlords often use to acquire homes. While Black homebuyers might suffer the most from corporate landlords’ purchasing patterns, anyone looking for an affordable first home or to transition from renting to homeownership will find themselves at a similar disadvantage when trying to outcompete corporate investors. Corporate landlords, unlike most homebuyers, do not solely rely on mortgage financing, giving them an additional advantage over owner-occupants when buying these homes.

Lewis also sees the exorbitant fees charged by corporate landlords and their specific targeting of an already shrinking affordable housing stock as impediments to Black homeownership and wealth-building in the Charlotte area. For homeowning Black Charlotteans who are considering selling their homes to investors at a profit, Lewis cautions them to think carefully about the steps that would follow that decision: It has become incredibly difficult to find affordable homes within a distant radius beyond the city center, and it is unclear where such households would be able to relocate. Part of that knowledge comes from her own experience. When Lewis finally felt comfortable and capable enough to buy a home in recent years, she was unable to find any affordable options in Charlotte and turned to renting instead. “I have more people wanting to stay in Mecklenburg County, and they are fighting to stay in Mecklenburg County,” she says.

—Bo McMillan

Reggie Jackson explores: Milwaukee—Corporate Landlords with a Lowercase ‘C’

My wife and I live within the seventh Aldermanic District in Milwaukee. Of all the aldermanic districts within the city, ours has the largest number of homes owned by out-of-state landlords. The five largest of these firms own 367 houses within our aldermanic district. They also own nearly 20 homes within five blocks of our home.

LLCs based outside of Wisconsin have been on a buying spree in Milwaukee. As Marquette University researcher John D. Johnson has noted, many of them are corporations that are only capitalized in the low millions of dollars (think single-digit to just over $10 million) and are not publicly listed and/or backed by major investment funds, compared to the large single-family rental home companies backed by institutional investors and under the lens of Congress, like Invitation Homes and American Homes 4 Rent. These include SFR3, a California-based company owned by Jonathan Kibera and Thomas Fallows, former classmates and members of the Harvard rowing team who purchased their initial 56 properties in Milwaukee on Halloween Day 2017 for $4.55 million. The largest of corporate investors in Milwaukee single-family homes is VineBrook Homes, based in Dayton, Ohio, which now owns over 800 houses in Milwaukee.

The growth of corporate-owned single-family homes and duplexes has closely aligned with a decline in homeownership in Milwaukee. From 2005 to 2019, the number of owner-occupied properties dropped from 107,000 to 93,000. Meanwhile, LLC ownership of homes quadrupled from 1,300 properties to more than 5,800. In the aldermanic district where I live, the owner-occupancy rate dropped from 74 percent to only 54 percent over that same time period.

The extent of the growth of corporate landlords in Milwaukee has been especially acute since the end of 2020. In December 2020, SFR3 owned 95 properties. They now own 258 properties. VineBrook Homes owned just 250 properties entering 2021. They have acquired 583 properties over the past 21 months.

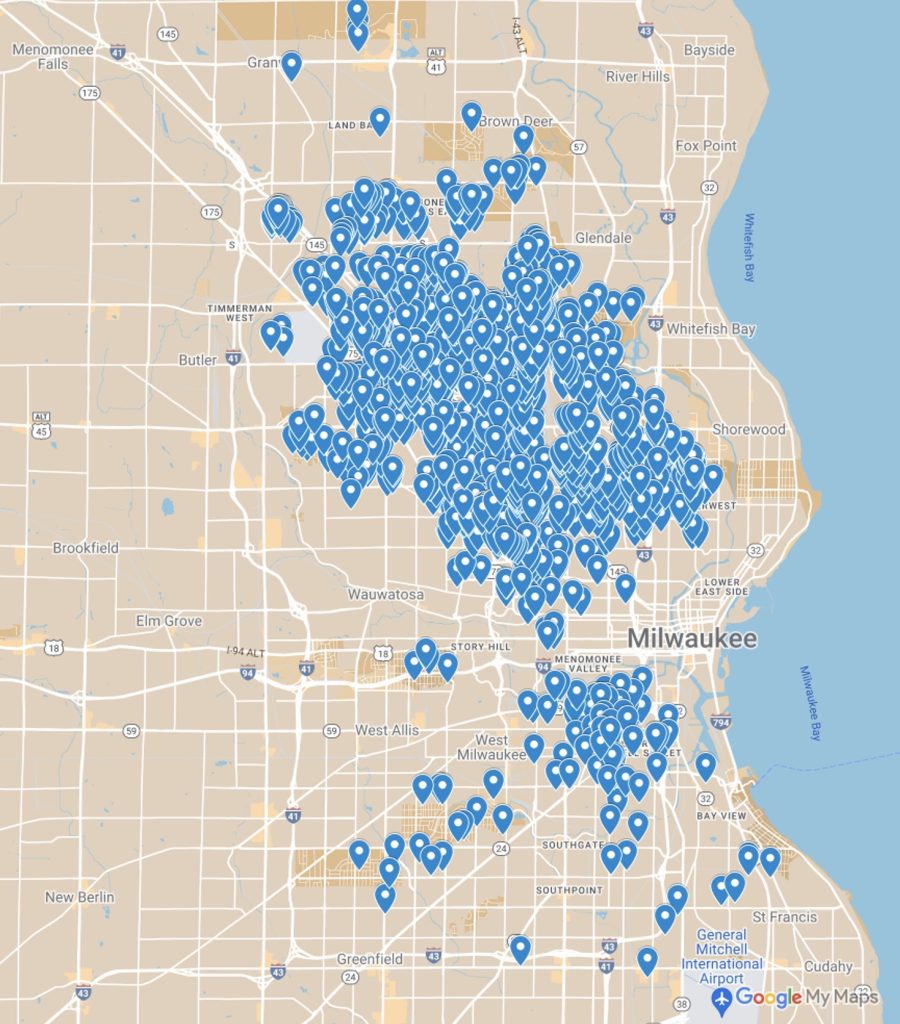

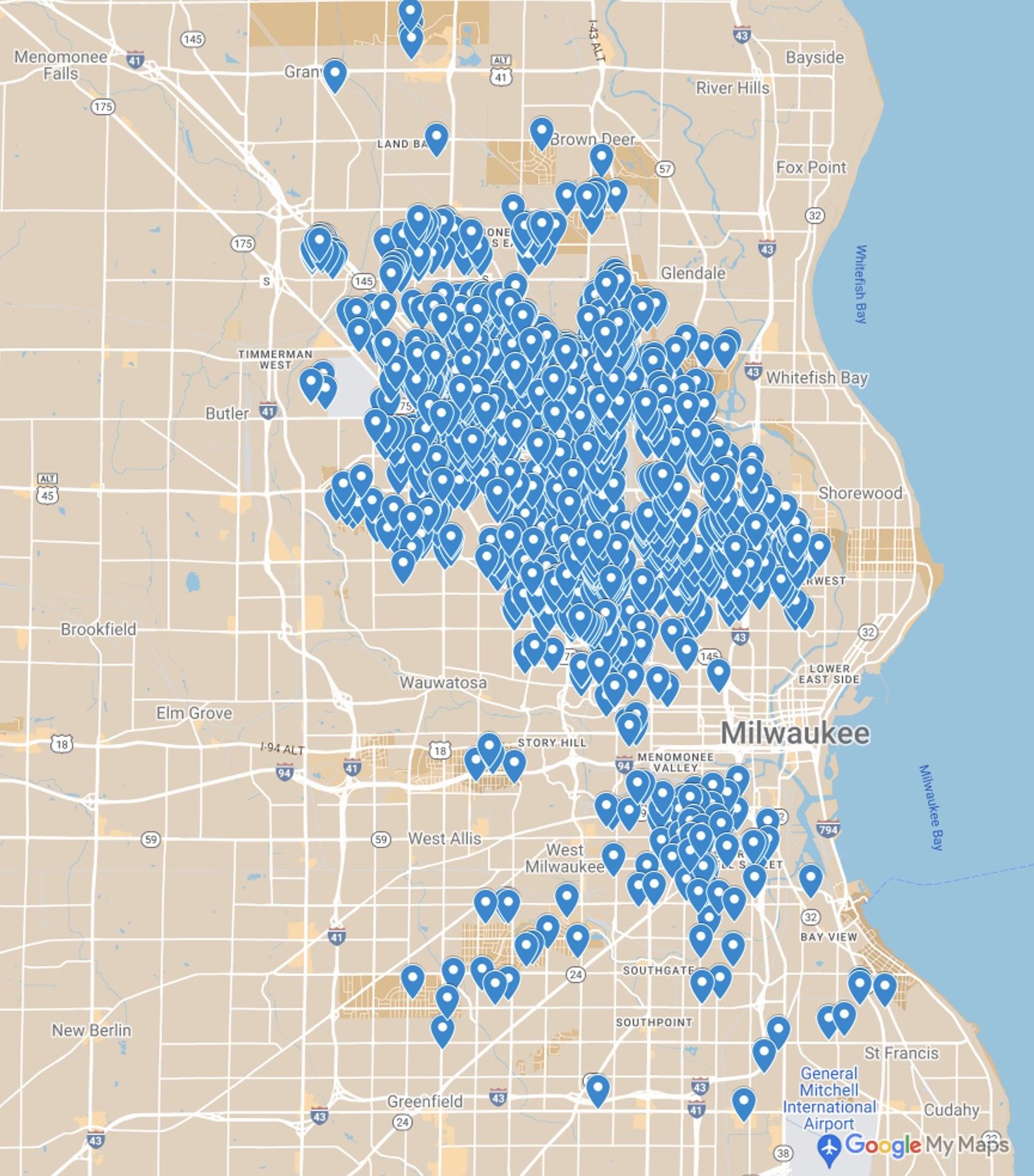

Map of VineBrook Homes’ properties in Milwaukee. Note the preponderance of homes are on the mostly Black north and northwest sides of the city, while few properties exist in the white portions of Milwaukee to the southwest and southeast. Map made by Reggie Jackson using Google Maps

By April 2021 out-of-state landlords owned 14 percent of all rental homes in Milwaukee. They have been drawn to the city for its lower-than-average housing costs. For this reason, the properties they have been purchasing are primarily clustered on the north and west sides of the city, in predominantly Black neighborhoods. These lower- to middle-income neighborhoods now have 3 of every 4 homes owned by corporate landlords. These include companies like Torrance, California-based Highgrove Holdings Management Inc., which brags on its website that its Milwaukee properties “provide tremendous cash flow of 12 percent to 18 percent returns annually.” Those returns come at the cost of Milwaukee’s Black households, who face the largest homeownership gap in all of the nation’s 50 largest metropolitan areas except Minneapolis. The median cost to rent in Milwaukee is $1,657 while the median mortgage is just $1,184.

Many Black residents who now rent in Milwaukee and who struggle to compete with the cash offers made by corporate entities are therefore spending more to live in rental homes than to build equity in their own houses. The impeded Black wealth-building and homeownership bodes poorly for a city that has the fourth-worst rates of upward mobility for Black youth of the nation’s largest 50 metros. It also has the lowest median Black household income of all.

Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson responded to the growth of corporate landlords in the city by saying, “Sometimes they buy these homes sight unseen. Stick a body in there, jack up the rent and use it as cash cow. They’re disconnected absentee landlords . . . they really don’t care about the fabric of our neighborhoods.” His statement has some basis in fact. In a 2021 story for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, John D. Johnson and reporter Mike Gousha found that out-of-state landlords have higher eviction rates and incur more building code violations than local landlords. Concentrations of these investors in Black neighborhoods may also ultimately lower property values for Black homeowners living near or in those neighborhoods in Milwaukee. Though a recent paper in the Journal of Real Estate Economics found that home purchases by institutional investors drove up local home values more than rises in nearby neighborhoods, another recent article from Housing Studies on investor purchases of foreclosed homes in Detroit suggested this might not hold true in softer markets like Milwaukee compared to hot markets like Charlotte.

One organization in Milwaukee has taken aggressive steps to slow down the impact of out-of-state landlords. ACTS Housing is launching an acquisition fund to compete with investor landlords in the city. They plan to create a fund with $11 million eventually that will allow them to purchase homes and sell them at affordable prices to city residents. They hope to purchase 100 homes in 2023 to begin the process.

ACTS Housing President and CEO Michael Gosman told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel that “[i]f we’re going to offer great homeownership opportunities for families, we have to make sure there is inventory available to them that meets their needs.” In order to guarantee that inventory, groups like ACTS Housing and local governments will have to outcompete and preempt corporate landlords who are also targeting that same housing stock.

—Reggie Jackson

What Can Be Done?

As stated earlier, the most impactful solution to curbing corporate landlordship would be to redress the segregation that has enabled them to exploit inequalities in the housing market. Beyond this, according to our research and interviews with local stakeholders, there seem to be five basic actions that could be pursued by groups interested in curbing corporate landlord activity and expanding Black homeownership and wealth-building. These are:

- Increase tenant rights and rental regulations in local areas. As Lewis and others have said, corporate landlords make significant profits off the long list of atypical fees and charges they levy on tenants. According to one paper, tenant chargebacks alone made up almost 16 percent of American Homes 4 Rent’s core revenue. Both American Homes 4 Rent and Invitation Homes have also named increased tenant rights as risks to their businesses in publicly available annual reports. Outside of getting local governments to expand tenant rights and regulations, tenants can also organize unions that, if spread across companies’ footprints, would be many thousands of tenants strong.

- Acquire and preserve naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) stock. Corporate landlords are targeting affordable, entry- and starter-level homes in most of the housing markets where they are active. “Naturally occurring” or unsubsidized affordable housing makes up the single largest share of the country’s affordable housing stock. (An important note here—many “naturally occurring” affordable homes are merely homes devalued due to segregation.) Given that NOAH is fast disappearing in the current housing market, local governments and nonprofits should take aggressive steps to acquire NOAH where it exists to preserve both affordable rental housing and to maintain some of the most accessible on-ramps to homeownership for Black renters. Recently some larger corporate landlords have announced cutbacks to their own home-buying programs. Governments and nonprofits should take advantage of this indefinite window to do their own purchasing of existing affordable housing, perhaps by using untapped American Rescue Plan Act funds to bolster acquisition programs.

- Maintain Black homeownership through foreclosure diversion. Whether by tax foreclosure or by bank foreclosure, foreclosed-upon properties provide a cheap source of new acquisitions for corporate landlords. Given that Black households face disproportionately high rates of foreclosure, foreclosure diversion programs are one key way to ensure Black homeownership rates do not fall while at the same time averting those homes potential snapping-up by corporate landlords. For homes that local governments do foreclose upon, ensuring that they do not fall into corporate landlords’ hands is crucial. The White House recently announced plans for federal agencies to extend by 30 days the waiting periods during which defaulted homes are made available only to nonprofits and owner-occupants. Local governments could also take similar measures to more responsibly dispose of homes seized through tax foreclosure.

- Build more entry-level and affordable housing for rent as well as for purchase. A long-standing housing supply shortage has driven up housing costs across the U.S. and made entry- and starter-level homes especially scarce. Corporate landlords look to that scarcity as a means of guaranteed profit, especially since this scarcity does not appear to be abating any time soon. In the midst of current uncertainty among home builders that has led to construction slowdowns, some groups are beginning to look to local governments to go about their own construction programs to create housing for a variety of income ranges. Called “social housing” by its proponents, such programs use their own revenues to self-sustain costs and continue construction instead of using unreliable grants to fill financing gaps. Pilot “social housing” programs are already underway in places like Montgomery County, Maryland, and Colorado.

- Incorporate data on corporate landlordship into Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing efforts. In 2021, the Biden administration issued orders for the Department of Housing and Urban Development to begin collecting data and implementing the portion of the Fair Housing Act that calls for the dismantling of housing segregation in addition to the end of housing discrimination. Since local government entities responsive to HUD will ultimately collect that data and enforce any affirmatively furthering fair housing actions, this process can be both a method to inform community members about the scope of community landlords in their area and a force to correct inequities they generate.

Terrific analysis. I’m sure you are aware, but the Lincoln Insitute of Land Policy has developed a geospatial mapping tool that identifies neighborhoods most vulnerable to corporate investment in single family homes. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/article/2023-07-who-owns-america-mapping-technology-property-ownership-center-for-geospatial-solutions

Rent control is needed to mitigate the profits of this cruel system. Incentive programs for housing restoration, landlord mitigation and other possible benefits should only go to locally owned homes/landlords to dampen the speculative frenzy of this greedy dynamic.