This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Photo by Flickr user J Biochemist, CC BY-NC 2.0

As we continue to grapple with the high cost of housing for renters and would-be homebuyers, knowledge of who owns properties can be a valuable tool for developing strategies to promote affordability. Much attention has been paid to the role of institutional investors in the single family housing market and the impact of COVID-19 on so-called mom and pop landlords—shorthand for non-corporate owners—and their interest in and ability to continue their businesses. Common to both storylines: an implicit recognition that who owns a property can dictate what happens to it.

Ownership scale and physical proximity of the owner’s address to his or her portfolio are important indicators of opportunities to engage on property- and local-level concerns. For those reaching out to owners to partner on preserving affordability of rental properties, for example, working with a cohort of owners or managers controlling a dozen properties each will have far more impact than working with a group of owners responsible for only one or two properties. A community concerned about a property with repeat code violations might want to know about other properties under the same owner to keep close tabs on those homes as well. And a jurisdiction’s response to violations may differ between a non-local, large-scale owner using neglect as a business strategy and an individual owner with a second property nearby that has fallen into disrepair because of cash flow problems or lack of business acumen.

Publicly accessible records of ownership are the key to being able to develop effective policies and programs. But it’s not easy. Nobody checks a box anywhere indicating a particular type of ownership, and many investors actively try to hide their activities.

Why Land Ownership Records Are Public

One of the earliest public records of land ownership is the Domesday Book, which cataloged landholding in England in 1086. While it was designed to provide William the Conqueror with an assessment of the country’s wealth in order to levy taxes, it also served to provide landowners with unimpeachable proof of their claims to their land. As land was sold, passed down, leased, subdivided, aggregated, encumbered, and otherwise transacted over time, clear chain of title open for all to see—that is, in the public record—was in the interests of individual owners and society at large. Publicly recording all of these things meant that competing claims to land could be resolved by reviewing the history, and fraud would be minimized.

The practice of public recordation in the United States is as old as the Plymouth Colony, which had its first recorded deed in 1627. Massachusetts’s 1640 law to prevent fraudulent conveyances is considered the archetype for all state recording acts. In addition to “avoyding all fraudulent conveyances,” the law’s express purpose was “that every man may know what estate or interest other men may have in any houses, lands, or other hereditaments they are able to deale in.” A complete and open picture of land ownership is a key principle behind the public recordation of real estate transactions in this country.

Who Owns the Landowners

This is an argument in favor of greater transparency around the beneficial ownership of corporations found in the land records. A beneficial owner is anyone who either exercises substantial control over a company or who owns or controls at least 25 percent of the ownership interests.

In states where secretaries of states’ corporations data is available, common ownership of individual LLCs can be traced, but this often requires some sleuthing. Moreover, when these LLCs change hands, no record of the change in ownership ever makes its way into the public land record.

This can be a problem when corporations own land. In researching ownership concentrations in Cleveland, I came upon several individuals who formed LLCs to buy up foreclosures and then sell them, but instead of selling the properties, they sold the LLCs and stayed on as the agent for the LLCs. This workaround meant those sales were never recorded and won’t show up when anyone looks up the ownership of those properties. This not only deprives the public of knowledge of who owns them, it deprives them of the revenues from the recordation fees (which have risen considerably since the sixpence charged in 1640). I would never have uncovered this particular business practice if I had not been looking at corporate ownership data in conjunction with sales data. These changes in ownership were entirely hidden from community stakeholders monitoring neighborhood trends based on property sales, a common early warning indicator of possible gentrification.

Commercial property owners in Ohio have also used this tactic to avoid both conveyance fees and paying their full share of property taxes, as discovered by an investigation by Eye on Ohio.

To restore transparency to the land records, states could legislate that beneficial ownership of land must be recorded alongside any deed not in a natural person’s name and that any subsequent change in beneficial ownership must be recorded for the change to be valid.

This can be done. At the federal level, the Corporate Transparency Act (PL 116-283) already mandates reporting beneficial ownership information to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network as an anti–money laundering activity. Unfortunately, the law stipulates that this information will be held in a “secure, nonpublic database.” A version should be public.

Usable Data

The movement toward open data is now making records long locked away in inaccessible paper ledgers, truly public (at least in many places). But some jurisdictions continue to charge high fees for accessing digitized records, creating a significant barrier to communal knowledge. This furthers an imbalance between regular individuals and parties who can pay the costs for direct access or even, increasingly frequently, buy data from vendors that have merged property records with other personally identifying information.

Open data is not enough to get to full democratization of data. Open data makes land records, permits, code enforcement actions, and other property-related administrative information accessible to the public, but the agencies furnishing the information and the data engineers tasked with publishing it rarely (if ever) provide the necessary tools to turn that data into knowledge. Without proper—and accessible—tools, data-driven stakeholder engagement and data-informed policymaking will remain elusive.

One of the biggest barriers to democratizing the data is the fact that it is messy. Administrative records are replete with spelling errors and inconsistencies that make identifying portfolios of properties challenging. Standard spreadsheets like Excel or Google Sheets require exact matches to count items as being the same, but properties may be recorded first name followed by last name or vice versa, with or without a comma or middle initial, and that assumes no transcription errors. And then there are the multiple LLC names that all lead back to one owner.

The challenge and opportunity is to transform open data from seemingly endless rows, columns, and tables of names, addresses, dates, and so much more into meaningful information, and do it in a replicable, accessible way.

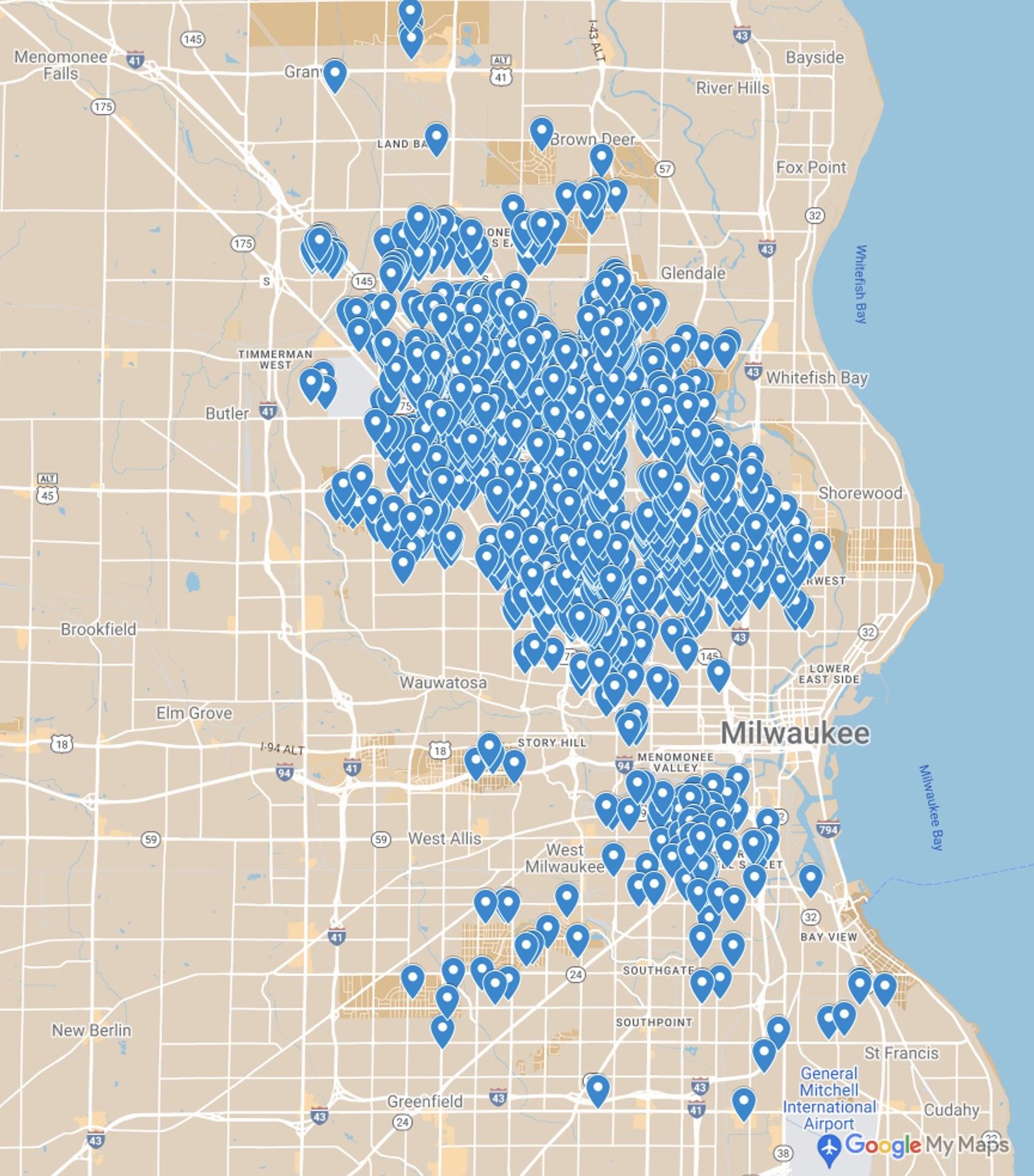

My research collaborators and I have been using open source software, beginning with Open Refine, which can cluster properties in messy data, identifying patterns and building a more accurate picture of who owns what. Looking at addresses and naming conventions, we can often find larger owners even when they’ve formed a different LLC to actually own each property. Getting this kind of information allows us to then identify the scale of ownership and different types of ownership, and that can empower stakeholders to make informed decisions for the communities where they live and work.

We hope our methods can increase democratization of data, and that policymakers follow suit to make the changes needed so everyone can again easily identify who owns the housing in their communities.

|

|

Comments