The era of cellphone videos has forced white America to finally acknowledge the obvious enough patterns of racial inequity in policing. But in other parts of society we cling, still, to the idea that racial inequity is the result of “a few bad apples” rather than a core feature of the system itself.

Among the most consequential instances of this willful blindness has been our approach to fair housing. In response to centuries of unjust housing and land use policies (public and private) that target Black people and others specifically based on their race, our fair housing laws enshrine an “all lives matter” approach which actively prohibits us from explicitly referring to race even in programs intended to undo the harm caused by this history.

A new generation of local housing policymakers is attempting to directly confront this history but fair housing law leads to convoluted policies that offer further racial equity only indirectly through income or geographic targeting. This attempt to address racial injustice by proxy has become one of the defining failures of housing policy today. Colorblindness is fundamentally at odds with what is strategically and emotionally necessary for us to move forward as a people.

Bearing Witness to a Crime

In 1966, the apartheid regime in South Africa forcibly displaced more than 20,000 people of color from their homes in central Cape Town’s District 6. The area, a dense and racially mixed working-class community with thriving businesses and homes, had been designated a “white area” under the Group Areas Act. Under the law, only white people were allowed to own or rent property in desirably located areas like District 6. Stores and homes were bulldozed to make way for new housing for whites only. People were forcibly relocated at gunpoint (sometimes taking only suitcases) to racially segregated townships on the cape flats, miles from public services and community institutions. Previously District 6 had been home to strong mixed-race community institutions including soccer clubs, musical groups, and churches. But the apartheid system required racial sorting, so these institutions were destroyed along with the buildings of District 6. Social capital built over decades was erased in months.

For Americans, it is easy to see this shameful moment as a violent crime.

What has been harder for Americans to acknowledge is that at the same time, American cities were doing something shockingly similar.

In just one typical case, San Francisco systematically destroyed its strongest African-American communities in what looks, in hindsight, an awful lot like a premeditated crime.

Urban renewal in San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood alone displaced at least 10,000 African-American people and a large share of the city’s Black-owned businesses. At one point the city was demolishing 40 buildings a month in the area. Unlike their South African counterparts, American planners expressed regret about the impact of these actions on African-American communities and offered reassurance that displaced people and businesses would have an opportunity to return to the rebuilt neighborhood.

Looking back, it might be tempting to see the failure to make good on relocation promises as an example of dropping the ball on a detail of implementation in an otherwise well-intentioned policy, but when you look at urban renewal in the context of the times, it seems clear that the wholesale displacement of much of the city’s African American population was quite intentional and that returning people to rebuilt neighborhoods was never a serious goal. In 1966, the city commissioned a plan that expressed dismay over the recent growth in the city’s African American population and proposed setting a target for reducing the Black population. Another report the same year called for the city to “move closer to standard white Anglo-Saxon Protestant characteristics.” Citing the racial composition of neighborhoods as a “blighting” factor, San Francisco targeted Black communities for demolition at a time when one study found that fully two-thirds of rental units in the city were being advertised as for “whites only.” No one at the time could have been surprised that the policy caused Black families to leave the city permanently.

Razed houses in Charleston, South Carolina’s Triangle neighborhood, as part of urban renewal efforts in 1973. Photo by Harry Schaefer, National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fewer than 4 percent of displaced businesses ever returned to the Western Addition. The Black population in the Western Addition and the city as a whole never recovered. San Francisco’s Black population fell from 13 percent in 1970 to less than 5 percent of the city today.

Nearly every city in America has a similar story. Like South African apartheid, American apartheid-era urban planning efforts devastated entire communities, leaving a legacy of inequity that is ever-present today, playing an outsized role in policy choices about how we grow our cities. Black families were displaced, businesses closed, land was taken away. Wealth stripped from Black communities made its way into white pockets. It is difficult to look at the totality of these actions and see anything other than a systematic, racially motivated assault on Black Americans.

South Africa has a name (“apartheid”) for the system itself which promoted segregation and inequity; in America we hide the crime by treating it as a series of isolated mistakes. By pretending that past harm was the result of some kind of one-time technical error rather than an ongoing system of violent crimes targeted at one racial group, we make it much harder to move forward.

In city halls across the country, a new generation of elected leaders is actively looking for ways to confront and repair the harms of apartheid-era housing policy. But their efforts are stymied by a surprising barrier: fair housing laws. Federal laws designed to prevent communities from unfairly discriminating on the basis of race are being applied to prevent cities from using race as a factor in the implementation of programs designed to remedy those past harms.

The Problem with ‘Reverse Discrimination’

In the early 1950s, white leaders in Dallas developed a strategy for addressing what they referred to as “the Negro Problem.” The city built 3,500 units of public housing on a single site in West Dallas and proceeded to lease it almost exclusively to Black families. A court later concluded that the project’s “primary purpose was to prevent Black families from moving into white areas of this city.”

In a series of lawsuits in the 1980s, courts found that the intentional segregation of African Americans into west Dallas violated the U.S. Constitution’s promise of equal protection for Black citizens. But when a federal district judge ordered the city to remedy this harm by building public housing in predominantly white neighborhoods, the Fifth Circuit Court overturned the lower court’s order on the grounds that because it used neighborhood racial composition to identify the new sites, it purposely discriminated against white residents on the basis of their race. As a result, the city was forced to cancel plans to build public housing in white neighborhoods and the city’s public housing stock remains highly segregated to this day. While the Second Circuit Court upheld race-conscious remedies in a very similar case in Yonkers, the U.S. Supreme Court’s refusal to hear either case has left public agencies in a situation where they cannot safely pursue race-conscious remedies even to undo the harm of their own prior actions.

Confronting Injustice by Proxy

This colorblindness of fair housing law has become second nature to many housing professionals. Policymakers who want to use housing programs to further racial equity are told that we should instead rely on income or geographic targeting in ways that will indirectly advance racial equity.

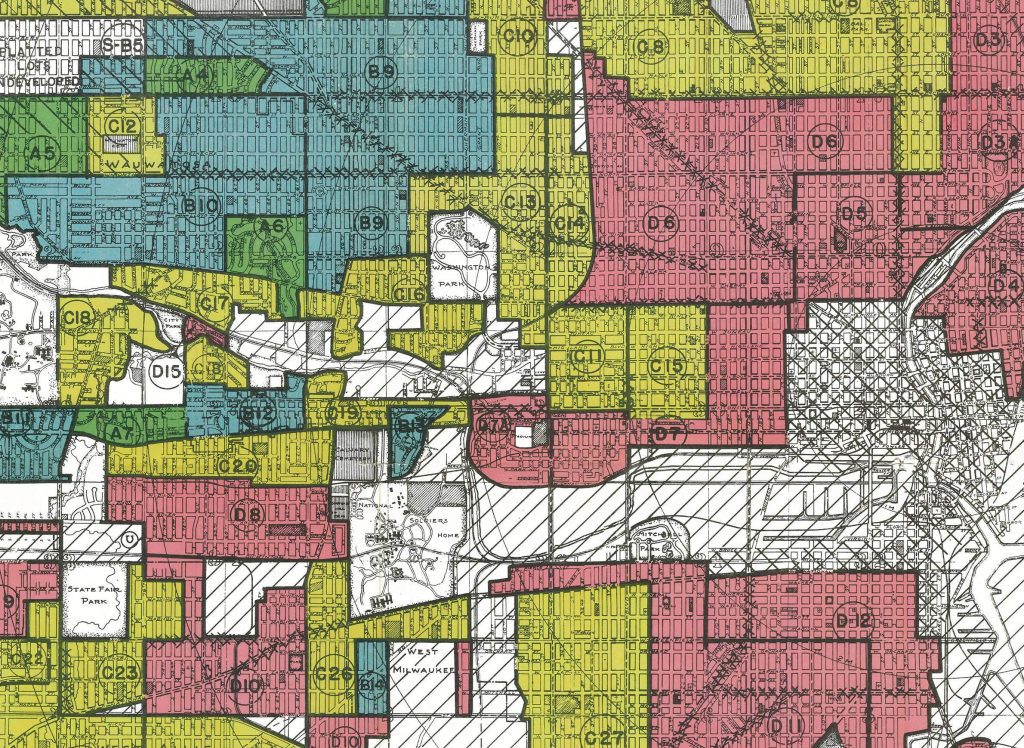

In 2019, presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren held up federal redlining maps as a clear cause of the lasting racial wealth gap but then proposed a federal investment program to promote homeownership, not for disadvantaged racial groups but instead for residents of areas that had been redlined in the past. The problem, some critics quickly objected, is that many of these redlined communities are, today, struggling against gentrification, and Warren’s program would finance not just longtime residents but also anyone new moving into these neighborhoods, in some cases fueling displacement of the very families it was intended to (indirectly) benefit.

CityLab pointed out that Warren’s ambitious proposal “neglects to mention race but seeks to address an historical racial injustice by proxy.”

When it comes to federal housing policy, Home Owners’ Loan Corp. redlining maps are the closest thing we have to damning cellphone footage. Above, a map of Cleveland. Photo by National Archives, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Like Trump’s Opportunity Zone program and Bill Clinton’s Empowerment Zones before that, Warren’s proposal pretended that it is neighborhoods that have been the victims of discrimination when, in any honest account, we must acknowledge that it is people (and specifically Black people and other people of color) who were discriminated against—not neighborhoods. Witness how quickly capital flows once race and income demographics start to change. Census tracts themselves have no need for government protection.

The Limits of Colorblindness

As a Black girl growing up in public housing in San Francisco’s Western Addition neighborhood, London Breed saw first-hand the results of urban renewal. So when Breed became president of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in 2015 (she is the city’s mayor today) she wanted to find ways to reverse this history and stabilize the city’s Black communities. The city adopted a series of measures intended to prevent the displacement of African Americans and other people of color. The measures included a Neighborhood Resident Preference, a program that reserves 40 percent of the units in new affordable housing for residents of the surrounding neighborhood. Without explicitly mentioning race, the policy clearly benefits Black and Latinx households because, not coincidentally, they make up a larger share of the residents in the denser areas where the city builds most new housing.

But even this proxy effort was too much. In 2016, the Obama administration blocked the city from implementing this preference in the name of “fair housing.” Because the preference has the impact of disproportionately benefiting some racial groups, it was found to violate the Fair Housing Act. Similar local preferences have long been used by white communities as a tool of racial exclusion, so it is understandable that the federal government would be cautious. But in this case, all parties agree that the policy would benefit Black households and it was blocked because of its potential to harm white applicants.

In an act of bureaucratic courage, San Francisco has implemented this local preference in spite of HUD’s prohibition (only applying it to projects not funded with federal money). The city’s initial results show the limited potential of addressing racial injustice by proxy. The neighborhood preference significantly improves the chances of a Black applicant winning San Francisco’s affordable housing lottery and being given a chance to lease a new affordable unit.

But it also painfully illustrates the futility of this kind of proxy strategy. So strong are the headwinds arrayed against Black economic mobility that after winning the lottery, Black applicants fail to qualify for units at a much higher rate than Asian and white lottery winners. The net result is that, even with the boost provided by the neighborhood preference, Black applicants are less likely than white applicants to end up living in a San Francisco affordable housing unit. By enforcing race neutrality in the lottery process while the overall economic conditions that determine eligibility remain far from race neutral, fair housing law ends up keeping Black applicants at a lasting disadvantage.

Race consciousness that is merely implied is not race consciousness at all. Often housing professionals trying their best to address the legacy of racial discrimination without actually mentioning race are surprised by the level of pushback from communities of color. By taking on race without talking about race, we deny people (and ourselves) the transformative power that comes with a clean and honest accounting of past injustice. And, inevitably, that limits the impact of the work we undertake today.

Restorative Justice

What would it look like if we were to address the legacy of racial injustice directly rather than “by proxy”? What if we admitted publicly what we were trying to do instead of trying to hide it?

One model for this is a growing movement in the world of criminal justice known as “restorative justice.” Restorative justice is an approach to addressing crime that typically brings victims and offenders together to identify harms that have been caused and outline steps that could be taken to help “put things right.” Restorative justice is used in a number of very different contexts where the specific practices look quite different, but they share an underlying focus on the victim’s needs rather than on punishing the offender. These processes generally involve circles or conferences where victims, offenders, and other community members come together to discuss the harm that has occurred.

One of the key insights of the restorative justice movement is the notion that restorative actions are helpful both for victims and offenders. Even in the case of crimes such as murder where no restoration is possible, victims are often able to articulate steps that offenders can take to make their healing process more effective.

It would be easy to dismiss the movement as some kind of new age liberal wishful thinking. But what is perhaps most striking about the recent interest in restorative justice is the degree to which it is driven by hard data. Study after study confirms that restorative approaches to justice are not just a little better but vastly better than incarceration when it comes to reducing someone’s chances of re-offending.

Can we apply these lessons to larger-scale societal harms like urban renewal, redlining, and housing discrimination? Obviously, this is not a perfect analogy—restorative justice focuses critically on the role of individual offenders. But, if redlining and urban renewal were crimes, the offenders were not only individuals or even specific government agencies, but society as a whole.

For people whose families and communities were directly harmed by this historical process, it was a crime just the same. People carry with them a legacy of trauma that bears a striking similarity to the experience of victims of other violent crimes.

What is asked of us as a society is a “putting right.”

What Would Restorative Justice Look Like at a Larger Scale?

In Cape Town, after the fall of apartheid and the end of white rule, the city faced a difficult choice. Following the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994, South Africa launched a truly unprecedented Truth and Reconciliation Commission, charged with documenting and redressing the crimes of apartheid. Cities like Cape Town had to wrestle with how to apply this approach locally. They could ignore past harms like the destruction of District 6 and try to quietly move on. Or they could try to take immediate action to fix the damage with the risk they would get the details wrong.

Cape Town’s District Six Museum documents the memories of families impacted by forced removal including a massive oral history archive and a collection of tens of thousands of family photos. Photo by John M via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Instead, Cape Town chose a more intentional route. The city started with a process of listening to those who were directly impacted. It launched a Commission on Restitution of Land Rights which first set about documenting the experience of thousands of displaced District 6 residents. The commission captured the personal stories of thousands of families. Former residents created a District Six Beneficiary Trust to coordinate the claims of people who had lost property. A Settlement Agreement between the city and the beneficiary trust outlines a framework for equitable redevelopment of the area including new housing for displaced families as well as others. While the process remains highly contentious and is still far from complete decades later, it provides a glimpse into what restorative housing policies could look like in American cities.

What Is Stopping Us?

What keeps American cities from undertaking similar reconciliation processes? One worry I hear is that if we engage people who have experienced traumatic harm as a result of public action, we will create an expectation that society will take action to repair that harm. And since many doubt that our cities are prepared to put these wrongs to right, we fear that engaging impacted communities would be unfair. This is a mistake. Our denial of the continuing relevance of these crimes is no favor to the families who were violently dislocated. Instead, by downplaying the crime, we magnify the power of these events to shape our cities today and into the future. The way forward is to call these crimes by their true name and fully face the harm that they caused—even before we know how to put things right.

People don’t believe that we have the public will to really take restorative action at the scale that would be appropriate. But, of course we don’t. How could we? So long as we resist a true accounting of what happened, we couldn’t hope to undertake repairing the damage. The urge to jump over the listening process right to the part where we fix the problem is understandable—but unhelpful.

Restorative justice is related to reparations, but they are not the same thing. While discussions of reparations sometimes focus on providing compensation for economic losses, restorative justice focuses on restoring relationships.

Margaret Urban Walker writes that in contrast to processes that focus on compensation alone, restorative justice “emphasizes material and practical amends that address victims’ losses and needs, but restitution and compensation in a restorative framework play instrumental and symbolic roles in repairing relationships, including the role of adding weight to expressive interpersonal gestures such as apology . . . The direct concern of restorative justice is the moral quality of future relations between those who have done, allowed, or benefited from wrong and those harmed, deprived, or insulted by it. In some cases, compensation or restitution will be indispensable to signify full recognition, respect, and concern to victims. In other contexts, material reparation might be unnecessary, and in no cases is it, by itself, sufficient for signaling appropriate moral regard.”

The problem with redressing past racial violence “by proxy” is that it fails at the emotionally necessary task of atonement. A race-blind neighborhood preference, even when it has an indirect effect of helping Black applicants, simply does not function emotionally as an act of racial healing. And without concrete actions explicitly tied to aiding Black applicants, all the public proclamations of regret for past discrimination ring hollow.

What Can We Do?

Much as I would like to see a national truth and reconciliation process, it seems unlikely that the federal government could provide the right initial arena for this kind of healing discussion. Instead, the federal government could explicitly allow and encourage local and state level experiments that directly and explicitly target the legacy of racial discrimination in housing. A federal Restorative Housing Act could, for example, explicitly authorize non-colorblind remediation efforts when they are undertaken by governments within the context of a restorative housing process that has successfully engaged impacted communities to document the harms of specific racially discriminatory housing policies and practices.

A restorative housing process would first identify specific documented historic actions that appear reasonably likely to have resulted in specific documented inequitable outcomes. These historic actions might include discriminatory policies enacted by or on behalf of a city, state, or the federal government agency but should also include racially discriminatory private actions that government failed to act to protect communities from. In other words, these processes should address the harms caused by government action as well as by government inaction.

Making such a formal statement does not require prior commitment to any particular solution. Our leaders should anticipate that making this kind of statement will generate pressure to take immediate action, but they should be prepared to let this pressure build while we engage a broader set of the population in a conversation about this legacy and how we might respond.

Instead of imposing a single national resolution which will inevitably seem inadequate in many communities even as it seems draconian in others, the federal role, initially, could be to get out of the way and allow local governments to engage in these discussions and experiment with racially explicit remedies in the places that are ready for them.

The right way to design programs that take the legacy of racial discrimination into account is not obvious. But, today, federal law prevents us from learning how to do this important thing. By strictly limiting race-conscious housing policies, federal fair housing rules stand in the way of this necessary reckoning.

This article is on the mark, but its not necessary to wait for new legislation from a dysfunctional Congress. The Fair Housing Act already provides authorization for race conscious restorative practices—the duty to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing. The problem is two fold: 1) Local, state & federal agencies (especially HUD itself) have wholesale ignored this part of the Act, or at best related, treated it as merely one policy option among many competing policies, rather than a mandate. 2) Conservative courts have generally provided recalcitrant governments and private entities with cover by raising the bar so high for race conscious remedies and then using the Constitution’s Equal Protection clause to strike them down where they have been attempted.

A dysfunctional Congress and reactionary courts with tortured constitutional interpretations will remain a problem. But activists can use AFFH to force governments and private housing providers out of their recalcitrance. A vigorous AFFH process, that couples restorative practices with ruthless historical documentation, could provide the factual record and legal justification for race conscious remedies that are tailored to the specific local history and current circumstances. There is no excuse for using the Fair Housing Act as an excuse.

Barbara, Thank you for the beautiful and moving response. I really hope you are right. Several people have pointed out to me privately that, with the current Supreme Court, the chances are low for any meaningful changes being upheld.

It would be great if we could use AFFH to enact strong enough race-conscious housing policies (and I certainly am not qualified to have my own opinion about how far we can take that). But, I agree with you that we absolutely don’t need to wait for a better Court (or Congress). I love the phrase “ruthless historical documentation.” I think my main suggestion is that we need to put less energy into finding cleaver (but overly subtle) vehicles for skirting the federal law issues and relatively more energy into facilitating clear and explicit public processes for owning up to this history – even in the face of real uncertainty about how we will be able to take strong actions to repair those past harms.

Instead of restorative housing policy to correct for historic racial divides, let’s graduate to its broader lens: restorative economic policies adopted to accomplish the same goals, but on a grander, impactful scale. We need to look at the ideological content from the “urban planning” model, as well as its extension, the “economic development” tool, to accomplish these ends.

Housing discrimination is concrete, economic policy adoption is subtle. I would replace the “urban planning” model with a socioeconomic framework, whereby economic well-being is central to any idea of civic success. But, this approach has never been attempted.