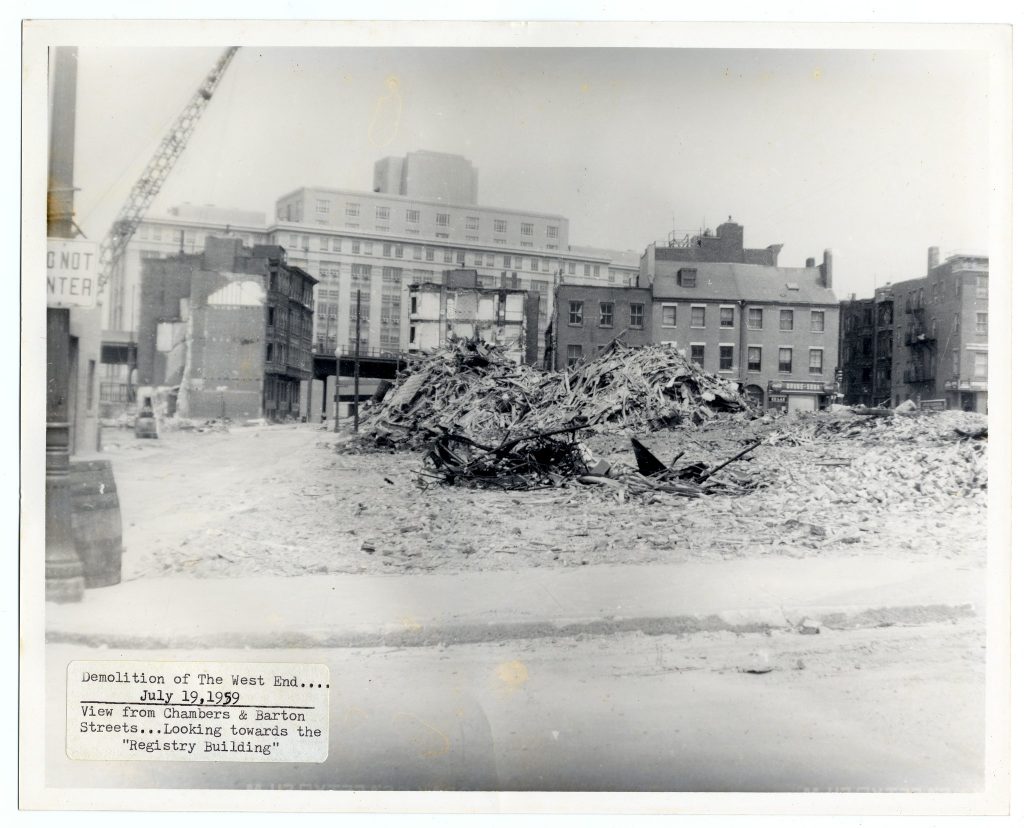

Piles of rubble from building demolition, as seen from Chambers and Barton streets in Boston, in July 1959. Photo by Boston City Archives via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

In 1914, John D. Rockefeller—America’s richest business tycoon—had a public relations problem. On April 20 of that year, Rockefeller’s private security guards, along with the state militia, attacked striking workers at a Rockefeller-owned mining camp in Ludlow, Colorado, killing 66 people including two women and eleven children who suffocated in a pit beneath their tent when a fire ignited by the fighting sucked all the oxygen from their shelter. The public blamed Rockefeller for their deaths in what became known as the Ludlow Massacre, while newspapers around the country excoriated him as a greedy robber baron. To cleanse his reputation, Rockefeller hired Ivy Lee, one of the first practitioners in the emerging field of public relations. Lee suggested that Rockefeller burnish his image through charity. Over several decades, Rockefeller made sizable grants to a variety of educational, religious, and scientific organizations.

Many other business moguls followed Rockefeller’s example. They created family or corporate foundations to divert public attention away from their business practices. Automobile tycoon Henry Ford, a blatant anti-Semite and racist who bitterly fought his workers’ efforts to unionize, was among the most successful at rehabilitating his image. Today, the Ford Foundation is a bastion of liberalism.

Among the notorious names who sought to rehabilitate their image is Boston real estate developer Jerome Lyle Rappaport.

And at least for him, it appears to have worked.

After Rappaport died on Dec. 6, 2021, at the age of 94, the Boston Globe’s obituary described him as a “philanthropist” and “civic leader.” The Harvard press office released a statement from President Lawrence Bacow, who said that “Jerry worked tirelessly to improve the world by better connecting ideas and people” and praised his “dedication to public service and public policy.” Diane Ring, dean of the Boston College Law School, proclaimed that Rappaport was “a visionary leader.” Boston’s new Mayor Michelle Wu praised Rappaport’s “commitment to public service.”

Those descriptions would be a hard pill to swallow for the thousands of residents of Boston’s former West End, who were bulldozed out of their homes in the late 1950s to make way for Rappaport’s Charles River Park apartment complex, or the tens of thousands of Boston renters who have been displaced by gentrification and rising rents, which Rappaport encouraged by using his political influence to weaken the city’s tenant protection laws.

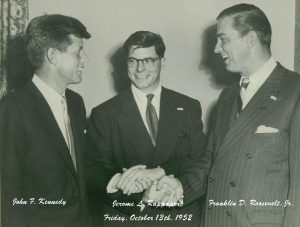

Congressman John F. Kennedy, left, and Congressman Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr., right, of New York pose with Rappaport during a Democratic Party fundraiser at the home of Boston newspaper publisher Harry Harwich in 1952. Photo by Rappaport Foundation via Wikicommons, CC BY-NC 2.0

Rappaport was never elected to public office, but he was one of Boston’s most influential power brokers. He was a political insider who used his connections to enrich himself at the expense of the city’s working-class residents, including the 7,000 people who were forced out of the West End.

For several generations, students and practitioners have examined the West End as a case study in misguided urban planning. It is not simply a story of bureaucratic wrongdoing. It is a story about how power is wielded and abused.

Rappaport’s Rise

By the end of World War II, Boston had become an economic wasteland. Boston’s business elite had decades earlier written off the city. Only one private office building was constructed in the city between 1929 and 1960. The banks and insurance companies refused to invest in new buildings, housing, or modernizing industrial plants. The economic backbone of the region—the textile, leather and shoe industries—had packed their bags and headed toward Dixie or overseas to be near lower-wage workers and lower taxes.

Boston’s corporate elite hated Mayor James Michael Curley. It was not only that they were Republicans and he was a Democrat. Much of their hostility was a mixture of upper-class snobbery and opposition to his New Deal-style government programs for the poor and working class, such as the construction of Boston City Hospital.

The flamboyant Curley had developed an intensely loyal following among the city’s working class. He padded the city’s budget to provide jobs for his campaign workers and voters, and taxed banks and businesses to pay for public works projects that employed working people, many of them Irish immigrants and their children.

In the late 1940s, Boston’s business leaders regrouped and decided there were profits to be made after all—if they could build a new city of corporate office towers and luxury apartments. Their plans were made possible when Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949, a new federal program that the nation’s real estate industry had lobbied for. It was called “urban renewal.”

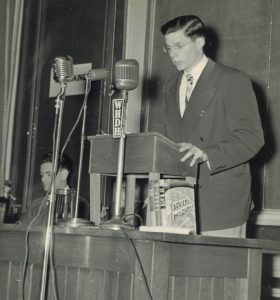

That year, Rappaport, who grew up in New York, was an ambitious 21-year-old recent Harvard Law School graduate. At Harvard, he began a speaker series that invited famous politicians, academics, and business leaders to speak on campus, later using those connections to catapult his own career.

Jerome Rappaport addresses the Harvard Law School Forum, 1946. Photo by Rappaport Foundation via Wikicommons. CC BY-NC 2.0

According to a story in the Boston Globe at the time, Rappaport told college students, “Boston is a dead city, living in its past. If you want to be successful in any business, get out of Boston.”

But Rappaport did not take his own advice. Instead, in 1949 he joined forces with Henry Shattuck, a well-connected Republican corporate lawyer, to defeat Curley by supporting John Hynes, the city clerk, in the mayoral election. Rappaport created a “Youth for Hynes” committee, composed primarily of upwardly mobile students from local universities such as Boston College, Boston University, and Northeastern University. They focused their campaign on overturning Curley’s corruption and the need for Boston to overcome its image as an economic backwater that provided few career prospects for young college graduates, finding support in the business community and among middle-class voters.

Hynes won and served as mayor for 10 years, from 1950 to 1960. The political forces behind Hynes’ campaign also supported a revision to the city’s charter that changed the 24-member City Council, elected by wards, into a 9-member body elected at large. That weakened the voice of Boston’s working-class neighborhoods and gave business groups—who could fund citywide, at-large elections—a stronger voice.

Once in office, Hynes hired Rappaport as one of his top aides. Rappaport was profiled and praised in articles in Readers Digest, Redbook, and other publications as the young reformer who toppled the Curley dynasty and would help shape the “new Boston.” In 1951, the Boston Jaycees (the Junior Chamber of Commerce) named him their Man of the Year.

Following the Hynes campaign, Rappaport played a key role as a bridge between the city’s establishment business leaders and its Irish politicians. Rappaport and Shattuck organized a business-sponsored civic group, the New Boston Committee (NBC) which held forums and issued reports about the need to turn Boston’s downtown into a center for retail and service businesses, corporate headquarters, and upscale housing. They also supported candidates for mayor and City Council who embraced corporate-centered urban planning. Between 1952 and 1954, 10 of Boston’s 15 elected city officials were endorsed by the NBC. But by 1954, the NBC had fallen apart from internal squabbles, many of them rooted in opposition to Rappaport’s brash and ambitious personality, which rubbed people the wrong way.

However, the NBC had succeeded in organizing Boston’s business elite. At one 1957 meeting of corporate executives, Robert Ryan of Cabot, Cabot & Forbes, an old Yankee real estate firm, told the audience: “Gentlemen, we are marked men. Bostonians at mid-century . . . Boston is crying for leadership. We have been tapped by fate, for which we should be ever grateful and give thanks.” Ryan made clear what kind of leadership he had in mind. “Boston has reached the point,” he said, “where private funds cannot be invested in Boston in any amount equal to filling the need until those funds can be assured a chance of return on investment.” High taxes on business, he pointed out, was the main culprit.

This new attitude inspired business leaders to create several organizations, including the Boston College Citizen Seminars, the Greater Boston Economic Study Committee, and the Coordinating Committee. The latter group was the pinnacle of Boston’s ruling class. It consisted of 14 corporate leaders who were soon nicknamed the Vault, because their mystery-shrouded meetings were held at the Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company. The Vault played an outsized role in Boston politics from its formation in 1959 through the 1990s.

“If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home Now”

The city’s business establishment, along with its daily newspapers and the Catholic archdiocese, persuaded city officials to create the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) to carry out the local version of the urban renewal program. Hynes and other city officials targeted the West End for redevelopment, proposing to build mixed-income apartments near the downtown (another part of which was razed to build what is now Government Center). They hoped to stem the exodus of middle-class families to the suburbs and justified their decision in the name of “slum clearance.”

But the West End was not a slum, as sociologist Herbert Gans discovered when he lived in the neighborhood and wrote a book about it called The Urban Villagers in 1962. Gans described the West End as a lively, working-class community of three- to five-story apartment houses—not the blighted slum the city’s establishment claimed. A potpourri of Italian, Jewish, and other immigrant groups, and a small number of African Americans, lived together in relative harmony, their lives centered on their families and the churches, synagogues, schools, settlement houses, and small shops that dotted the West End, at the foot of Beacon Hill.

In April 1958, the BRA gave West End residents and shopkeepers formal notice that their homes and businesses would be taken by eminent domain. The community itself was not well organized and had no representation on the city council, then composed of at-large members. Because this kind of wholesale neighborhood destruction was unprecedented, few West End residents knew how to fight city hall.

By 1960, the 52-acre neighborhood was practically gone.

The city government promised West End property owners that they would be fairly reimbursed for their buildings and that owners and renters alike would be relocated to comparable low-rent housing, including in new apartments built where their homes had been. All these promises were broken. In a 1964 study titled “The Housing of Relocated Families,” Chester Hartman—a city planner at Harvard—discussed how West Enders were dispersed all over the Boston area. Almost all of them had to pay considerably more rent after they were forced to move. Marc Fried, a psychology professor at Boston College, interviewed the displaced residents and found that they suffered emotionally from the loss of their community ties, calling his study “Grieving for a Lost Home.”

After Rappaport left city hall, city officials chose him as the developer of the West End. The original plan called for building 2,000 new units of housing, half of them affordable to the West End families about to lose their homes. But Rappaport used his connections to persuade city officials to change the deal and allow him to construct 2,300 units of luxury apartments, all of them beyond the reach of the working-class former West Enders. The city sold him the land for the bargain-basement price of $1.17 a square foot (or $11.29 in today’s dollars). Additional federal funds and insurance subsidized the development itself. The John Hancock Insurance Company—one of Boston’s most prominent companies—underwrote the mortgage for Rappaport’s Charles River Park development.

The bulldozing of the West End was the first of many urban renewal projects in Boston. Across the city, new office buildings, government buildings, convention halls, and luxury housing transformed the city’s skyline, physical landscape, and demographics.

Political squabbles between Rappaport and the next mayor, John Collins, who served from 1960 to 1967, delayed construction of the project. Charles River Park was finally completed in the early 1970s. In addition to the 2,300 luxury apartments, it included two swimming pools, a tennis club, a hotel, two office buildings, parking garages, and a shopping center. They still stand where the houses and shops of the West End once did. Ironically, the luxury high-rise towers are most famous for a sign that was visible from one of Boston’s main thoroughfares: “If you lived here, you’d be home now.”

The demolition of Papa’s Café on Leverett Street in Boston’s West End, 1959. Photo by Boston City Archives via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

The destruction of the West End as well as the demolition of large parts of the predominantly Black neighborhood of Roxbury demonstrated to many Boston residents the danger of urban renewal, sparking an upsurge of activism through the 1970s in the South End, Charleston, East Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester. Neighborhood residents pressured the BRA to focus on rehabilitating rather than razing residential buildings. Some leaders of those grassroots movements later became elected officials or joined local and state government to serve as allies of neighborhood activists.

As Jim Vrabel describes in A People’s History of the New Boston, these organizing experiences taught residents the skills of fighting political and business power. In one of their biggest victories, activists in different Boston area neighborhoods joined forces to stop the proposed expansion of the Inner Belt, a highway that would have circled around most of Boston but cut through Roxbury, Cambridge, and Somerville, causing disproportionate harm on poor communities. The federal funding originally intended for the highway was shifted to expand public transportation.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, tenants’ rights became a major focus for Boston activists, leading to successful struggles to win rent control and protections against evictions—some of which were reversed in the 1990s, in which Rappaport played a significant role.

Rappaport never expressed any regret for his role in the destruction of the West End, one of the most tragic chapters of Boston history. Nor did it harm his political power. He served as president of the Rental Housing Association and vice president of the Greater Boston Real Estate Board, two powerful lobby groups that opposed any form of tenant protections. For decades, his fundraising ability and political clout were so effective that the local news media dubbed him the “10th city councilor” when Boston still had only nine council members. (Voters changed the charter again in 1981, creating 13 city council districts, four of them at large.)

But Rappaport didn’t stop at the West End. In 1974, Rappaport persuaded his close friend and beneficiary Mayor Kevin White and the City Council to exempt Charles River Park from the city’s rent control law. The next year, he convinced them to weaken tenant protections by adopting vacancy decontrol, which removes apartments from rent control when a tenant moves out. In 1980, he was a strong backer of the business-sponsored Proposition 2 ½, the property tax-cutting measure, telling the Boston Globe that landlords would lower rents if it passed. When it won with 56 percent of the vote, Rappaport notified his tenants of rent increases.

Rappaport used the profits from Charles River Park to expand his real estate empire around the country. In 2006, Boston Magazine estimated his net worth at $300 million.

He eventually turned his real estate empire over to some of his children, but he was unable to translate his wealth into a political dynasty. In 1990, his son Jim, running for the U.S. Senate as a Republican, lost to incumbent Democrat John Kerry by a 14 percent margin.

Rappaport never completed his West End project. A 1.5-acre parcel near North Station remained undeveloped for more than a quarter of a century. Soon after Ray Flynn took office as mayor in 1984, he met with former West End residents and then announced a public competition to build affordable housing on the long-vacant parcel. The competition was stalled when Rappaport sued the city, asserting his right to develop the site. Appraisers hired by the BRA valued the property at $15 million, but Rappaport insisted that he should get it for about $100,000, its 1960 value. In 1990 the Massachusetts Appeals Court upheld the city’s rights, clearing the way for the development. A few months later, the city selected the Boston Archdiocese’s Planning Office for Urban Affairs, which had a long track record of building affordable housing, to transform the vacant parcel into a housing development.

In 1995, to Rappaport’s chagrin, a 183-unit mixed-income housing complex called Lowell Square was built on the site, named after one of the old neighborhood streets eliminated by urban renewal. The building includes a West End Museum that tells the history of the bulldozed neighborhood, with former West End residents serving on its board.

Rehabilitating Rappaport’s Reputation

Rappaport sold off the Charles River Park development in 2000 and expanded his efforts to cleanse his reputation by donating money to high-visibility institutions. In 2000, he endowed the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston at Harvard and the Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy at Suffolk University. The latter program moved to Boston College School of Law in 2015, thanks to a $7.5 million grant from Rappaport. Ironically, one of the recipients of a Rappaport fellowship at Boston College was Michelle Wu, who won her recent mayoral race in part by proposing a new rent control law, an idea that Rappaport bitterly opposed throughout his life.

Rappaport also spread around his wealth to Smith College, Massachusetts General Hospital, McLean Hospital, the deCordova Museum, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Jerome Rappaport, left, speaks to Professor Alasdair Roberts at Suffolk University Law School. Photo by the Rappaport Center via Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Rappaport’s public relations strategy obviously paid dividends. In 1998, for example, Suffolk University—a recipient of Rappaport’s largesse—awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. On his 88th birthday in 2015, the Boston City Council declared Aug. 15 to be “Jerry Rappaport Day.” In a cruel twist, they named a new street in the West End “Rappaport Way” in his honor.

Upon his death, the Globe obituary and tributes from officials at Harvard, Boston College, and elsewhere portrayed Rappaport as a selfless do-gooder rather than a rapacious developer.

From his earliest days, Rappaport justified his political and business influence-peddling as serving the greater good. “I believe that democracy’s greatest enemies are those who would sacrifice the welfare of millions of people through misrule, merely to hold power or to make money,” Rappaport told Redbook magazine for a flattering profile of him in 1952.

However, Rappaport’s career is a case study of greed and hypocrisy. He spent much of his life making money at the expense of Boston’s poor and working-class people. Like many other business titans and corporations, Rappaport doled out funding to museums, universities, hospitals, and nonprofit groups that serve the poor in order to divert public attention from his outrageous business practices. Today, we still see family and corporate foundations channel their funding to elite organizations that uphold the economic and political status quo. And, ironically, some of the most liberal foundations include those founded a century ago by robber barons who would certainly oppose many of the groups and causes that now benefit from their largesse.

There have always been a number of super-rich Americans with progressive values who have donated money to movements for social and economic justice that dismantle the systems of privilege through which their families, and themselves, prospered. The Liberty Hill Foundation in Los Angeles, the Haymarket People’s Fund in Boston, the Bread and Roses Community Fund in Philadelphia and many others were started by people who believe in the motto “Robin Hood was right.” Boston’s history is filled with people who used their wealth and power to promote the common good.

But Jerome Rappaport was not one of them.

Brilliant piece, Peter. Evocative of my own neighborhood’s demolition of comparable acres in Atlantic City during the Urban ( “removal”) Renewal years. For decades the only “ redevelopment” there was the local rabbi’s affordable senior housing building and Donald Trump’s Taj Majal Casino!!

The struggles that led to the formation of Boston’s Southwest Corridor Land Development Coalition to address the land taken for highway development through Roxbury, Jamaica Plain and the South End, inspired many of us to join your efforts in the Flynn Administration years and devote our careers to community-sponsored revitalization while resisting gentrification.

Meant to write Taj Mahal Casino.

Nice job, Peter! Fills in lots of details about Rappaport’s bio that I didn’t know.

One small correction: the New York Streets Urban Renewal demolition in the South End, preceded the West End in the 1950’s. That’s the neighborhood where Mel King was born and raised. It was a multiracial working class community, cleared for “industrial/commercial” use, following a Herald Traveler “expose” of alleged “slum” conditions, called “The Shame of the Cities”. I recall that the average “relocation” payment to the 1,000 people who were displaced by 1957, was something like $2.50 per household (SEPAC Housing Report).

The site remained vacant for several years. Of course, the main commercial tenant that eventually built there, was the Boston Herald.

Enjoyed learning from this!