Photo by John Guccione via Pexels

In March 2020, Congress created the Paycheck Protection Program, better known as PPP. It is a federal loan program designed for companies with fewer than 500 employees to keep their employees on payroll in spite of pandemic-induced hits to revenues. The loan would be forgiven if businesses lived up to their obligations to retain employees.

Several other business-support programs were rolled out as well: the Economic Injury Disaster Loan, or EIDL, retooled a program normally used to support businesses in areas hit by natural disasters; the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility bought up corporate bonds of large corporations to ensure continued liquidity; and the Main Street Lending Program supported otherwise healthy businesses hurt by the pandemic.

Real estate firms were among the businesses that took advantage of these programs. Just in the state of Florida, 3,760 residential real estate firms received Paycheck Protection Program loans, many seeking to support just one or two employees but others obtaining funding to support several hundred, according to Project on Government Oversight data. Approximately $278 million was lent to Florida real estate firms.

It makes sense that Florida residential landlords would have applied and been deemed eligible for PPP and other assistance. After all, thousands of Floridians lost jobs due to the pandemic, or were forced to deal with family health concerns when the pandemic hit. It turns out, however, that at least some Florida landlords and property managers took millions in federal aid that allowed them to operate with reduced rental income, only to file evictions against nonpaying tenants anyway, even while state and federal moratoriums were urging landlords to avoid displacing residents.

Focusing on three urban Florida counties (Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, and Orange), we found 95 landlords who received some form of CARES Act support but still filed evictions against tenants between April 2020 and March 2021, when state or federal moratoriums were in effect. Florida law offers few protections for tenants; it can take less than three weeks for a family to be evicted from their home even though the impact that these evictions have on their lives will continue for much longer. There are not only emotional ramifications but mental, physical, and financial consequences. Even tenants who settle with a property owner will have an eviction on their record, making it difficult to rent in the future.

[RELATED ARTICLE: How State and Local Governments Can Avoid Mass Evictions]

To be clear, the Paycheck Protection Program did not bar landlords from filing evictions. Landlords who pocketed large PPP payments while also filing evictions against struggling tenants—sometimes many tenants—were not breaking the law or violating the terms of the loan. But from a broader policy perspective it is clear that federal programs here contradict one another’s goals, supporting companies that then engage in behavior that is at odds with important public health and humanitarian concerns. This highlights the troubling and all too familiar disconnect in federal policy, where business promotion policies and social welfare policies operate on separate, unequal, and even contradictory tracks.

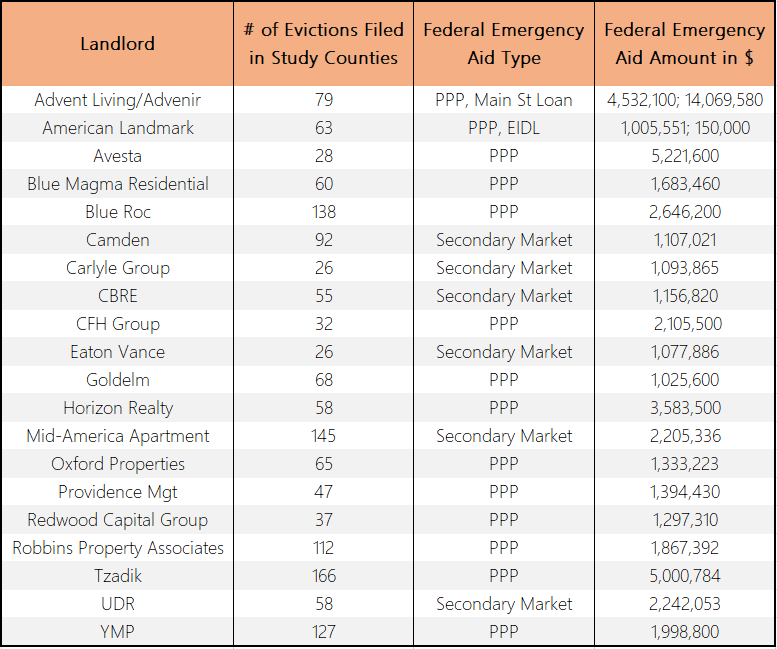

To spotlight real estate companies that benefited from federal largesse even as they dispossessed tenants, we highlight real estate companies that filed at least 25 evictions while receiving at least $1 million in CARES Act funding. We found the companies using the Private Equity Stakeholder Project database of corporate landlords with eviction filings. We then used the COVID Stimulus Watch database to see whether these firms had received federal CARES Act funding. Our research surely undercounts these cases, since many apartment managers who might not be considered corporations also received federal aid while evicting tenants. We also omitted landlords when we could not be sure they matched with the CARES Act database listings.

Corporate landlords in Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, and Orange counties receiving federal CARES Act funds of at least $1 million while filing at least 25 evictions from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. Courtesy of the authors

Beyond the numbers, case files associated with these evictions demonstrate that eviction filings have real, human costs.

Tzadik Management, a Florida-based company, has a large portfolio of rental properties in several cities. It is well known to tenant advocates for the poor condition of its properties and its heavy-handed eviction tactics; the company has been featured in media accounts of predatory rental practices. Unlike most real estate companies, Tzadik did not halt eviction filings even when Florida was under a very strict eviction moratorium; it filed 100 evictions from April to June 2020. One tenant who received an eviction notice in June answered with evidence that she had lost her job and was struggling to receive her unemployment benefits, but a default judgment against her was entered in October 2020 and the eviction completed in November 2020.

Blue Magma is a Tampa-based company that owns, manages, and invests in rental properties across the South. Blue Magma received media attention as a company pressing ahead with evictions even under the CDC moratorium. In Fall 2020, when the CDC moratorium had been ordered, it filed 23 evictions in Orange County in one day, including eight against households owing just a month of rent. Most of these 23 cases either ended with a “voluntary dismissal,” which often means the tenant agrees to leave, or in completed evictions.

Even when tenants filed court answers noting the protections of the CDC moratorium, the landlords featured here were likely to push ahead. A Camden tenant in Miami wrote in an October 2020 court answer, “Due to COVID I can’t work.” Nonetheless, the court issued a writ of possession a month later.

Advenir is based near Miami and has a portfolio that includes several southern states as well as Colorado, where the poor conditions of its complexes drew press attention a few years ago. A tenant responded to an eviction filing in an Advenir apartment, writing “My situation is the same of millions of American . . . because of this pandemic that hurts the economy so badly . . . I just need some more time, please!” A final judgment was issued about six weeks later, although the eviction does not seem to have been finalized against this particular tenant.

Too often, our public policies expose cruel ironies. In this instance, tenants have been evicted from their homes by billion-dollar conglomerates benefiting from taxpayer subsidy during one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. A number of these evictions were ordered at a time when county courts and their judges were meeting virtually, fearing it was not safe enough to have hearings in person, yet somehow finding it safe enough for individuals and families to be removed from their homes.

There is no reason for the federal government to subsidize landlords so they can evict tenants during a public health and economic emergency. Clearly there are federal housing policy makers who realize this: The CARES Act had established a higher level of protection for tenants in properties receiving a range of federal subsidies. Landlord recipients of PPP and other pandemic emergency aid, however, incurred no obligation to consider the well-being of their tenants by, for example, following local, state, or federal moratoriums, or working with tenants to secure emergency rental assistance.

It is probably too late to change PPP rules, but it’s not too late for federal policymakers to ensure that future programs designed to support private rental housing businesses also prioritize protections for vulnerable tenants in their rules.

Good story, but…

Isn’t the story why they got money in the first place? See ineligible list bullet 2… https://www.sba.gov/loans-grants/see-what-sba-offers/sba-loan-programs/general-small-business-loans-7a/7a-loan-program-eligibility%20

One would suspect these companies should neither have received loans nor forgiveness of those loans.