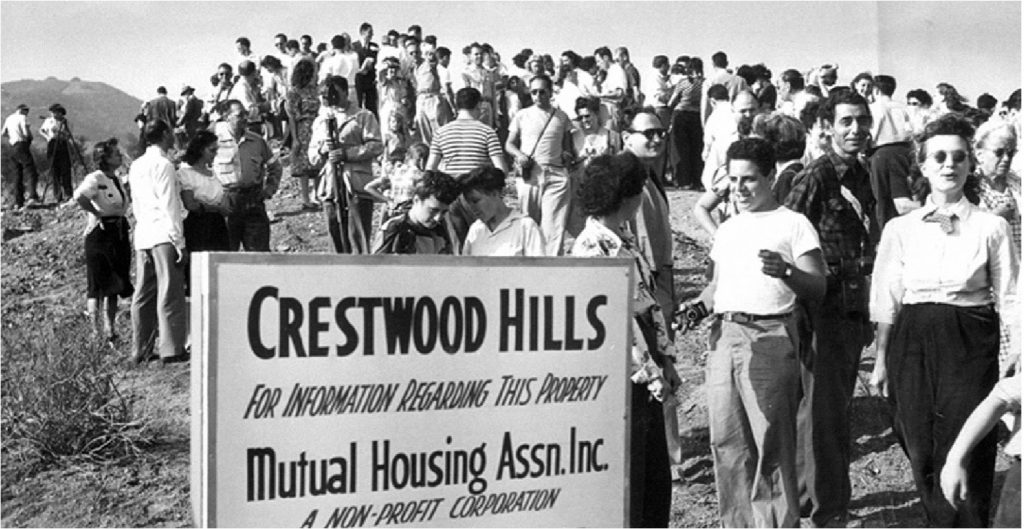

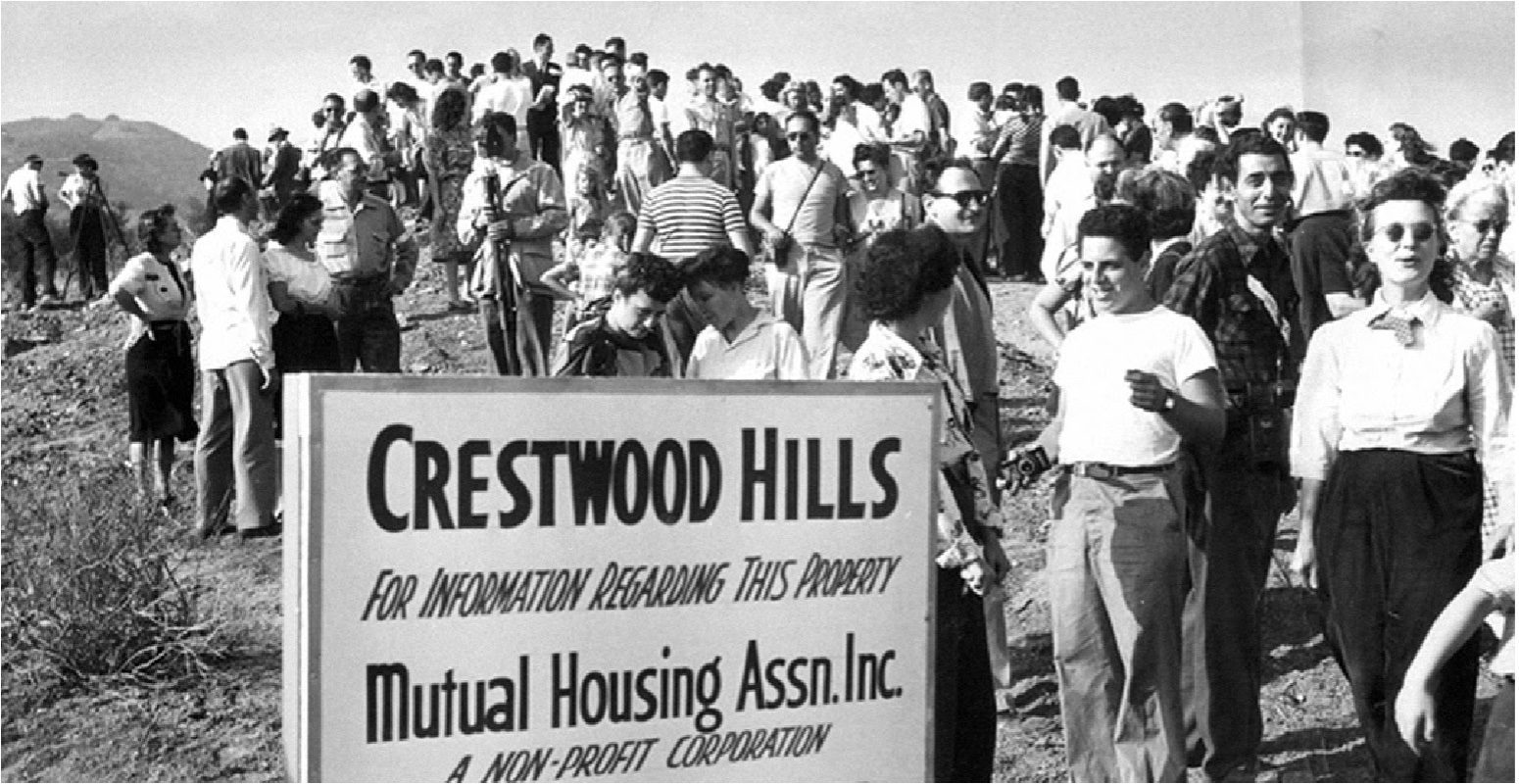

Crestwood Hills Association, the successor organization to a cooperative founded by returning servicemen, in 1952 had to accept the division of the collectively owned land into individual parcels, and it had to apply racial covenants to each lot in the first tract to get the FHA financing. By the time of the second tract, CHA had forced the FHA to follow the new law, and no racial covenants were required. Photo © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

Redlining is notorious for its role in segregating close to every city in the United States and blocking millions of people of color, namely Black Americans, from purchasing homes and building generational wealth. Lesser known is the fledgling movement following World War II to establish interracial housing cooperatives in a direct challenge to federally enforced segregation.

|

Community land trusts and cooperatives are two of the most prominent models of community ownership. In this Under the Lens series, we take a focused look at some of the ways these forms of community ownership are evolving. |

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. Thurgood Marshall was one of the lawyers who argued the case at the Supreme Court. Marshall was then legal counsel for the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Black and white Americans had fought all over the globe during World War II to defend democracy. However, the government that welcomed home “the Greatest Generation” while fighting the war with a segregated army had no desire to let returning Black soldiers live together with white ones. Fascism had been beaten abroad but not racism at home.

Regarded as the first suburb in America, Levittown on Long Island, New York, was the direct creation of U.S. government policy. The purchase of every single home in Levittown was insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Every Levittown homeowner’s contract barred buyers who were “not member(s) of the Caucasian race.” Thousands lined up to apply for America’s most publicized low-cost home ownership opportunity, but any Black people who turned up were turned away. The American future was bright for some, but due to racial covenants, it was legally off limits to Black Americans.

After Shelley v. Kraemer became law, Levittown removed the offending language from its contracts, but the FHA continued to insure loans only to white Americans who wanted to buy homes in Levittown. William “Bill” Levitt remarked at the time, “We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.”

Eugene Burnett was one of the million Black former G.I.s who were eligible for a federally guaranteed mortgage under the G.I. Bill of Rights. In 1950, he drove from his rental in the Bronx to Levittown to get in line for an application for ownership, but was told by a salesman, “It’s not me, but the owners of this development have not yet decided to sell to Negroes.”

As a result of these racist policies many communities remain segregated and inaccessible to Black Americans. Levittown has stayed segregated. As of 2017, only 1.19 percent of 51,800 Levittown residents were African American (617 people).

Federal policy has left at least a three-generation legacy of continued de facto discrimination. Home ownership gave 15 million white former G.I.s and their families a financial leg up on the American wealth ladder while 1 million Black G.I.s found their economic path totally blocked.

But some veterans came home wishing to build a better America in which they could live together, spurring a notable movement to establish integrated cooperatives.

Open Membership and the Cooperative Struggle against Racial Covenants

In several American communities, former G.I.s proposed new integrated communities. Winning the war against fascism abroad created interest in building a new America at home. Among these communities were a number of housing cooperatives. The many cooperative housing communities that sprouted after the war proudly followed the Rochdale Principles, (now the International Cooperative Alliance Principles) named after the English town that launched the cooperative movement in 1844. The Rochdale Principles were a set of organizational guidelines that distinguished cooperatives from the practices of regular investor-owned corporations and spoke to issues such as one member one vote, democratic control, concern for community, and profit-sharing, not to outside investors but only among user members. The first cooperative principle is open membership, which means simply that membership is open to all (no discrimination) who wish to avail themselves of the services of the cooperative and are willing to bear the responsibilities of membership.

Interracial housing cooperatives created after World War II were specifically meant to be inclusive of families of any color whatsoever. However, the same FHA that financed hundreds of post-war white suburbs was adamantly opposed to integrated suburbs. As a result, the FHA opposed the establishment of interracial housing cooperatives.

Among the projects blocked were the following:

Community Homes, Reseda, California: Based in Reseda near Los Angeles, the cooperative housing group had purchased 100 acres in 1945, upon which they planned to build 280 homes. They spent four years buying the land, paying for site plans and floor plans, and meeting with the local planning department. Yet it all stopped with the FHA’s decree that the inclusion of people of color jeopardized good business practice. A 1949 memo from Marshall to President Truman referred to the FHA’s prohibitive actions against Community Homes and York Center Cooperative Community in Illinois. The two co-ops were the only communities referred to in Marshall’s memo. Truman then included Marshall’s. However, it was an empty gesture. There was no penalty for discrimination in federal mortgage lending until 1968.

Peninsula Housing Association (PHA): Based in Ladera, west of Palo Alto, California, the PHA was formed in 1944 mainly by members of the local food cooperative. By 1946, the housing cooperative’s 150 members had purchased 260 acres of ranchland in the nearby Portola Valley. Denied FHA loans, the PHA ultimately closed and sold the land and plans to a developer who agreed to sell homes only to white homebuyers. In the 2010 U.S. Census, Ladera’s 535 households have a population of 1,426, of whom only three people (0.2 percent) are listed as Black. The legacy of institutional segregation appears to leave a permanent mark on a community.

Mutual Housing (now Crestwood Hills) Association: Four ex-servicemen returned to Los Angeles from the war with the idea of building an affordable integrated community based upon the Rochdale cooperative principles of open membership. By the late 1940s, the founders had recruited 500 members and with a $1,000 deposit per member, they had raised the funds to buy 800 acres in Kenter Canyon in West Los Angeles. At first, the FHA was against all the land being owned cooperatively. Then the FHA required the housing association to have racial covenants forbidding anyone other than a Caucasian to own and live in the housing. By 1952, with no progress and lots of development costs, the Mutual Housing Association was broke and had to dissolve. The resurrected Crestwood Hills Association (CHA) had to accept the division of the collectively owned land into individual parcels, and it had to apply racial covenants to each lot in the first tract to get the FHA financing. By the time of the second tract, CHA had forced the FHA to follow the new law, and no racial covenants were required.

An Exception that Proves the Rule: The Case of Sunnyhills

When Ford moved its Richmond, California, plant to Milpitas, California, in 1954, one issue seemed insurmountable. Ford had a large number of Black employees who worked in Richmond, and a number of them had worked on building Liberty ships during the war in the same community. However, there wasn’t any housing open for Black people in or near Milpitas, an hour’s drive from Richmond.

In the 1950s, the United Auto Workers union (UAW) and its president Walter Reuther had taken a strong interest in sponsoring integrated housing cooperatives for their members. Ben Gross, a Black UAW Local 560 leader in Richmond who was part of the national union task force on housing, was given the role of locating land near Milpitas. The UAW wanted to sponsor integrated housing cooperatives that could be built to accommodate the existing UAW Richmond workforce, which was about 20 percent Black.

Both local landowners and local governments were repulsed by the efforts of Gross and others in the Richmond UAW Local 560. Santa Clara County had few Black residents, and segregation and racial covenants had kept it that way. When the UAW pursued funding for the homes in the development, it ran into the same FHA rules, regulations, and culture that had stymied the other cooperatives. Once again, the FHA, local developers, and local government agencies looked like they were going to stop an integrated cooperative.

However, in this instance, the UAW officers pursued a new and different tack. The UAW arranged for a long-term master mortgage through the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae). In this case, the UAW applied under a new cooperative ownership program called Section 213 of the Federal Housing Act of 1950. Funded and staffed by the U.S. Congress two years after Shelley v. Kraemer, this new multifamily section no longer required racial covenants. The Cooperative Development Office of the FHA administered this program rather than the FHA’s single-family home program.

Critical to these major shifts was the Democratic victory in 1948 that secured control of both houses in Congress, allowing more progressive language in federal housing policy. As a result, the people hired in 1950 to run the new Section 213 program were hired under regulations written by a Democratic Congress whereas the staff who administered the Levittowns of America were hired under regulations written by a Republican Congress. Although Shelley v. Kraemer had changed the law, it was rarely enforced. There was no penalty for breaking the law. So because the staff at the FHA’s single-family home program as well as developers and local municipalities all wanted the suburbs to stay white, white suburbs continued to be exclusively funded.

Without the UAW’s national organizational and financial muscle, Sunnyhills would never have come about. Few other entities had the resources, people power, and time to withstand the years of struggle and the costs of litigation and development. Coming along a few years later than the other interracial cooperative efforts, Sunnyhills benefited from the legal and program changes that had been achieved.

Ultimately, Sunnyhills got built as an interracial cooperative, becoming the first one ever approved by the FHA. When Sunnyhills was finally mapped out, the UAW saw to it that Gross and other union leaders were perpetually honored. Gross Street in particular paid homage to the UAW-backed leader behind Sunnyhills. Due to his civic commitment, Gross went on to become the first Black mayor of any city in California, serving as mayor of Milpitas from 1966 to 1970.

Gross played one other unique role in U.S. history. When Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev visited the United States in 1959, President Eisenhower wanted Khrushchev to see the fruits of a vibrant postwar America. One afternoon, after a visit to an IBM plant in San Jose, Khrushchev was whisked off secretly to see Gross and his family in their home in Sunnyhills. Eisenhower wanted Khrushchev to see a home in the United States in an integrated neighborhood where Black and white families were living together. The Secret Service did not allow any photos to be taken and even confiscated the Grosses’ personal camera. The only U.S. housing seen by the leader of Russia was an interracial housing cooperative that 10 years earlier would not have been allowed.

Segregated Housing’s Legacy Today

It is painful to record that in that postwar era and economy that saw so many changes in American society, racism was brushed under the rug. The housing segregation fortified by the policies of the FHA then has built the society we live in now. America, of course, continues to have a whole lot of work ahead of it if the country wishes to build an integrated society. The legacy of the blocked postwar cooperative ownership projects—and of redlining more generally—is, of course, a central reason behind the nation’s large and still growing racial wealth gap.

Although in their time these cooperators did not always succeed, their efforts, along with those of the NAACP and other groups, for a better and racially diverse America were not in vain. It is hard to imagine the Fair Housing Act of 1968 coming to fruition, for example, without these earlier struggles to painstakingly, project by project, break down the edifice of federally supported housing segregation.

But that is not to ignore the enormous human cost that the participants in these efforts often faced. In almost all of the proposed communities described above, hundreds of people lost their life savings after dedicating years of effort to build interracial communities.

This article is dedicated to those brave cooperators who in fighting to overcome the color bar in housing did, through their considerable personal sacrifice, help bring an end to de jure discrimination and who remain, even today, an example to us all.

Reprinted with permission from Nonprofit Quarterly.

The beauty of this model is that it taps into the desire of Black and white people to live together. Whites currently worry that Black entry to neighborhoods will depress the value of White-neighborhood homes. Black people are told by politicians that they can assert power if they live in concentrated Black neighborhoods that can be grouped to create “Chocolate Cities”. Unlike the experience in the military where all races were mixed together, the current status is one of Black fear of whites and white fear of Blacks. Why? Because neither group knows each other on a personal basis – not living, working or attending school with the other. So the easy path is for nobody to cross the line into the other’s turf, and the model lives on as long as concentrations are kept. Jurisdictions that stray significantly from the demography of the US tend to fail to survive as desirable as population quietly drifts away to other places not seen as the territory of a dominant race.