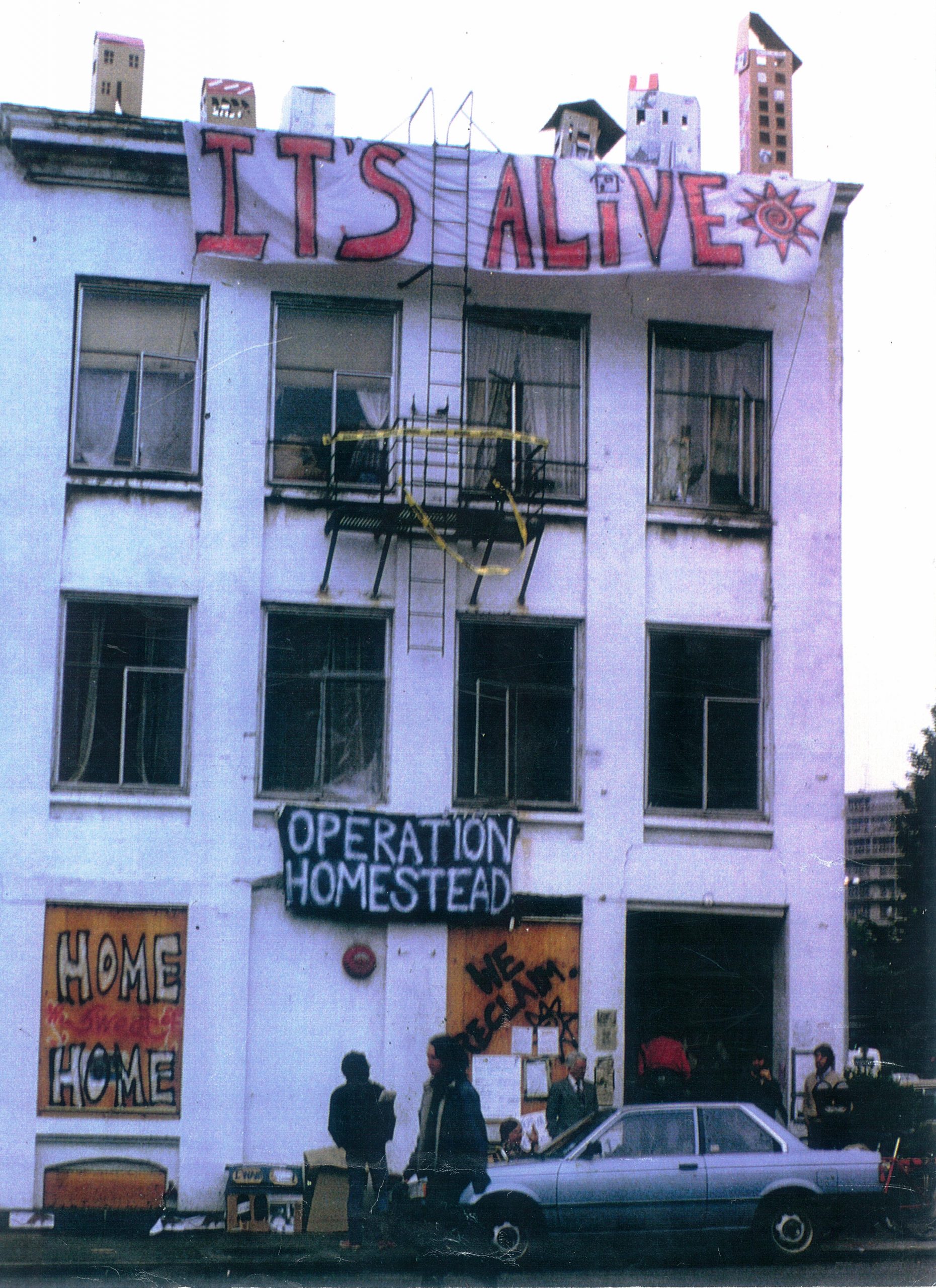

The Arion occupation in Seattle. Photo courtesy of the Low Income Housing Institute

On May 1, a small group of activists entered an unoccupied house in the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco. The building had been sitting vacant for several years and the activists planned to use it to house two homeless San Franciscans: Couper Orona, a former firefighter whose injuries left her unable to work, and Jess Gonzalez, a dog walker who had been living in a van for a year.

The group, calling themselves Reclaim SF, was joined by supporters in a caravan of cars and a small crowd out front, which included representatives from several other housing, homelessness, and social justice organizations.

“The hope was to provide Couper and Jess with somewhere to shelter in place at the very least for the pandemic,” says Kevin Goldberg, an organizer with Reclaim SF. “Housing is a human right. Everyone is entitled to safe and secure housing, not only during a pandemic.”

Forty-five minutes after Reclaim activists entered the home and unfurled a banner reading “End Homelessness, Reclaim San Francisco,” dozens of police officers arrived outside. Several hours later, after officers threatened to break down the front door and remove Orona and Gonzalez by force, the two women left of their own accord.

The occupation was reminiscent of the Moms 4 Housing campaign across the bay in Oakland in which a group of homeless mothers and their children occupied a long-vacant home owned by a large house-flipping company. That occupation lasted from November 2019 to January of this year when Alameda County sheriffs forcibly evicted the families. Moms 4 Housing is now working with the Oakland Community Land Trust to finalize the sale of the property to turn it into permanently affordable housing.

It was the Moms 4 Housing campaign that got Reclaim SF talking about using a similar tactic in San Francisco. The pandemic catalyzed the group to act. Goldberg says the group also drew inspiration from the Reclaimers, a group of Los Angeles activists who took over 13 vacant homes in March that the California Department of Transportation had purchased for a freeway expansion plan that never came to fruition.

But Reclaim SF’s May occupation echoes back to a long history of direct housing action. It has parallels in the work of housing activists taking over foreclosed properties in Chicago in the wake of the 2008 housing crisis; vacant apartment and hotel occupations in Seattle in the 1990s in response to the destruction of Single Room Occupancy housing; the radical building occupations organized by ACORN in Philadelphia and Brooklyn in the 1980s as those cities reeled from economic devastation; and beyond.

Low-income Americans were facing intertwining affordable housing and homelessness crises even before the pandemic. As the economic fallout from COVID-19 sends the United States’s unemployment levels skyrocketing and a disastrous eviction crisis unfolds for low-income renters, it’s valuable to understand the radical actions that previous generations of housing activists took to combat injustice and how they might play an important role in the affordable housing fight in the years to come.

A Foreclosure-Crisis Bailout for the Homeless

Willie J.R. Fleming co-founded the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign with Toussaint Losier in 2009. As the name implies, the group was focused on keeping people in their homes. The two were inspired by South Africa’s West Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign, which used direct action tactics like blockades to prevent authorities from evicting people. Fleming and Losier brought the tactic to Chicago, organizing groups to show up for eviction blockades at Cabrini Green public housing apartments and in other predominantly Black, low-income neighborhoods.

Their tactics soon evolved to include moving homeless families into vacant housing around the city as the foreclosure crisis left an abundance of abandoned, bank-owned homes in Chicago, especially concentrated in poorer south and west side neighborhoods.

Fleming says the inspiration for doing so came in part from the work of past Chicagoans. In the early 1930s, during the Great Depression, the Communist Party USA organized Unemployment Councils in cities across the country. One of its projects was to host eviction blockades and, if those blockades didn’t work, to move people back into their homes after the police kicked them out. In Chicago, the Unemployment Council would turn out large crowds for eviction blockades. In 1931, after a clash with the police turned violent and several blockaders were killed, tens of thousands people joined the funeral procession in protest, which influenced the city to pass a temporary moratorium on evictions and expand a rent relief program. Relief did not last long, however. According to historian Randi Storch’s Red Chicago: American Communism at Its Grassroots, the eviction crisis was once again accelerating by early 1932.

In the summer of 2011, the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign moved its first family into a vacant, foreclosed home on the south side. Martha Biggs was a member of the Anti-Eviction Campaign’s advisory board and a mother of four who’d lost her apartment when the building was foreclosed. Before the move-in, Fleming and other campaign members had already met with neighbors to tell them of their plans and begun renovating the house and cleaning up the lot. On move-in day, surrounded by activists and supporters, Fleming and Biggs held a press conference to announce their action.

The purpose of the announcement was threefold. Firstly, it was the campaign’s attempt to follow the rules of Illinois’s Abandoned Housing Rehabilitation Act, which allows nonprofits to take over vacant and blighted properties to house low-income people when they’ve been unoccupied for more than a year and are considered a nuisance. Secondly, it gave the campaign a chance to show the neighbors and greater community who would be moving in. And lastly, it was a chance to explain why they were doing what they were doing.

“We always made sure our messaging was clear,” says Fleming. “It just don’t add up. [The banks] leave a house vacant, which they get no money from, instead of keeping a family in there that can give you something towards the debt.”

He continues, “We had all the bailouts and homeowners still ended up without their homes. If Big Brother can’t fight for the people, little brother has to take the initiative.”

The Anti-Eviction Campaign followed that formula for several years. Fleming says the organization worked on more than 50 move-ins throughout the greater Chicago area. Some were short-lived. The Anti-Eviction Campaign often negotiated with banks that owned the foreclosures to provide “cash for keys,” where they would offer occupants funds to relocate. But in other cases, the new occupants were able to stay for years. Martha Biggs and her children lived in their house for over three years.

Fleming and the Anti-Eviction Campaign no longer do flashy home occupations. That’s in part because the legal risks were too high and in part because the organization has moved into more traditional housing work such as land banking and partnering with a community land trust to purchase foreclosed properties from banks to be used as affordable housing. As the COVID-19 crisis continues, the Anti-Eviction Campaign is working on tenants’ rights tool kits, organizing pro-bono legal aid for people who face eviction, and raising funds for emergency rental assistance. But even as his organization has moved toward the mainstream, Fleming has held on to his affinity for radical housing actions.

“I want to help make a difference in the absence of governments and banks,” says Fleming. “We the people have a responsibility. That’s why takeovers always mean so much to us. That’s why we support them today. But at the same time we’re realists. How long can that survive? You have to have a long-term plan.”

Squatting in Seattle

A 1983 report by the city of Seattle estimated that between 1960 and 1980, the city’s greater downtown area had lost 15,622 units of housing. Of the 13,093 units that remained in 1982, almost 4,000 were vacant and only 7,311 were considered affordable for low-income residents. Many of the units lost in those decades were Single Room Occupancies (SRO), the type of inexpensive boarding house rooms that low-income workers could afford without a subsidy from social service agencies. For some building owners waiting to cash in on redevelopment, it was less expensive to let buildings sit vacant than to pay for the repairs necessary to make them legally habitable.

By the end of the decade, Seattle had a homelessness crisis and a glut of abandoned buildings. A group of activists calling themselves Operation Homestead saw an opportunity.

“It was horrendous that in such a wealthy country there were people living on the street. . . . I didn’t have a complex analysis of the situation at the time. It was pretty simple. There were empty buildings and there were people on the street. Why can’t the two just go together?” says Ginger Segel, a Seattle-based affordable housing consultant who was part of Operation Homestead and worked for the Tenants Union of Washington at the time.

Segel helped Operation Homestead organize the occupation of Arion Court, a vacant 37-unit SRO building northeast of the downtown core. On May 19, 1991, a group of about 50 activists entered the boarded-up building, hung banners, and began cleaning up rooms. The building had been collecting code violations and had sat vacant for several months after its previous tenants were all evicted. Now the activists invited homeless Seattleites in and gave them somewhere to sleep.

The occupation lasted five days before police evicted them. While being evicted, Segel fell through a hole in the fire escape, dropped three stories to the ground, and suffered serious injuries that sent her to the hospital. “I think it helped keep us on the front of the papers for a while,” says Segel.

During their occupation, Operation Homestead was able to call on its relationship with other Seattle activists to negotiate with the building’s owners, two prominent members of the Seattle Asian community. Bob Santos, a legendary Seattle civil rights activist and advocate from Seattle’s Chinatown/International District, helped Operation Homestead make their case for staying in the building and operating it as housing for homeless residents. The owners ultimately said no, but the negotiations opened the door for the sale of the building to Seattle’s nonprofit Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI). The Arion re-opened three years later and LIHI still operates the building today as housing for people exiting homelessness.

It is a seemingly ideal outcome for an occupation, but Segel says the pace of change in the housing world can feel glacial for activists taking direct action. “It took years. The people we invited into the Arion Court to stay the night for those five days were not the people who benefited [and got housing when the building reopened].”

Most of Operation Homestead’s six occupations were shorter-lived and bore few results. But their 1992 occupation of the 113-unit Pacific Hotel in downtown Seattle followed a similar pattern to the Arion and helped open the door to Plymouth Housing to purchase the property and convert it into apartments for low-income residents, which the nonprofit still operates today.

ACORN’s East Coast Impact

A decade before Operation Homestead’s successes in Seattle, the nationwide community organizing collective ACORN was leading squatting campaigns in East Coast cities. In 1981, ACORN and the Inner-City Organizing Network helped orchestrate the takeover of 67 federally owned vacant houses in Philadelphia, just a few of the 22,000 abandoned homes that the city held at the time. Though officials were fearful of encouraging more squatting, they were also reluctant to evict the organized occupiers. President Ronald Reagan’s HUD secretary, Samuel R. Pierce, cut a deal with the occupiers in which the government would help them find somewhere else to live if they quit squatting.

In the following years, ACORN brought its tactics to Brooklyn’s poor, predominantly Black East New York neighborhood. New York City had an overabundance of city-owned vacant properties. When landlords abandoned their buildings and stopped paying taxes, the city seized the properties. According to author Hannah Doobz’s Nine Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance in the United States, New York City had more than 6,000 vacant properties in its possession in the mid-1980s and was unable to keep track of them all. The city also had more than 175,000 people on the waiting list for public housing. Already there were countless families occupying squats around the city. ACORN saw an opportunity to organize for lasting changes.

In his history of ACORN, Seeds of Change, author (and cofounder of Shelterforce) John Atlas writes that organizers distributed flyers at bus stops, grocery stores, and homeless shelters, reading “Do you need a home? Call ACORN.” They got hundreds of responses from potential occupiers. Participants were briefed about their legal rights and the risks they were taking, and ACORN’s expectations that they would fix up the buildings they occupied.

“People had no alternative, they didn’t have decent housing,” says Francine Streich, an ACORN organizer who led the Brooklyn squatters campaign. “They were willing to take the risk and obviously the reward was they had a place for their families to live.”

On June 15, 1985, ACORN began prying open boarded-up houses and moving families in. Over the next two months they ended up occupying 25 buildings. Their actions were met with fierce resistance from Mayor Ed Koch, who went as far as having one of the squatters’ houses demolished one afternoon while the family occupying it was out.

Though the mayor was opposed, ACORN had been building political support for its campaign from Catholic Charities, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, state Sen. Thomas Bartosiewicz, whose district included East New York, and others. It helped too that ACORN had done the groundwork to canvas the neighborhood and build support among the squatters neighbors. Before entering the homes, the would-be squatters went around the neighborhood introducing themselves. Streich says ACORN members in East New York hung signs in their windows saying “We Welcome the Squatters. That broad support eventually helped get ACORN a seat at the negotiating table with the Koch administration, where the activists ultimately came out on top.

In the end, Koch agreed to turn 58 vacant buildings over to the newly created Mutual Housing Association of New York to convert into legal homesteads. The administration also awarded $2.7 million in grants to help fund renovations and, critically, allowed the ACORN-organized squatters to keep their occupied homes.

The Legal Case for Squatting

There are some legal paths for squatters to take ownership of the building they occupy. Adverse possession laws vary state by state but allow an occupant to claim the title to a home if they live openly in the building, come and go through the front door, pay the taxes on the property, and continuously occupy it for a certain number of years without being evicted by the deed holder. In California, someone claiming adverse possession must stay continuously for five years. It has happened, but it is an arduous path to ownership.

Instead, most squatters’ campaigns are meant to shake up the status quo in order to spur change. In many cases, it was community and political support for the occupiers’ radical actions that led to the creation of permanent housing and other substantive reforms.

“All of this is civil disobedience,” says ACCE Institute legal director Leah Simon-Weisberg, who represented Moms 4 Housing in their eviction proceedings. “It’s not that you have a legal right to occupy a property. It’s that we’re in a crisis. . . . It was an action to literally get people housing and a way to get these companies to start selling these properties to the community and stop hoarding them.”

Fleming, of the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign, warns people that they need to be aware of the potential consequences of squatting. “Taking over property should be based on the laws of the area you live in. You could be hit with a breaking and entering charge, criminal trespassing on private property, and all that,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t think occupations still have value. “Takeovers are always a great tactic,” says Fleming. “I’m always going to be supportive of that, as long as the house is owned by a financial institution that’s not doing right by the people.”

The rationale for occupying vacant homes is rooted in a conviction that housing is a human right and that the injustice of letting people live and die on the streets while properties sit empty flies in the face of that fundamental belief.

Simon-Weisberg argued that housing is a human right in her effort to persuade the judge in the Moms 4 Housing case to permit the squatters to stay. She made the case that because there’s a human right to housing and California is experiencing an unprecedented housing and homelessness crisis, the court should grant the families the right to stay in the home.

The tactic didn’t work, but Simon-Weisberg points to a 2019 bill introduced in the California state legislature that would have declared housing a fundamental human right in the state. Had the bill passed, Simon-Weisberg thinks she would’ve had an even stronger case.

Similar tactics have been pursued at the federal level. In 2011, Illinois Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. introduced a bill to amend the Constitution and affirm that “All persons shall have a right to decent, safe, sanitary, and affordable housing, which right shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State.”

It did not pass. Fleming says, “If we gave Americans a constitutional right to housing, they could sue because homelessness would be a civil rights violation.”

A Return to Radical Tactics?

In Philadelphia, New York, Seattle, Chicago, and Oakland, squatters’ campaigns all grew from some form of housing and homelessness crisis. The economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a flood of evictions for America’s renters if the federal government continues to refuse calls for renter relief. Whether a new crisis leads to a new wave of radical housing activism that includes housing occupations and eviction blockades remains to be seen. But there are some signs it could.

In late May, an Oakland woman barricaded herself inside a motel room. Stefani Echevarría-Fenn is part of a group of activists who were paying for hotel rooms in which homeless residents can shelter in place, but the group was running out of funds. The action was a call to the city of Oakland to step in and provide rooms for the unsheltered.

In Minneapolis, a group of activists commandeered a Sheraton and housed more than 200 homeless residents as protests against police brutality raged in the city and around the country. The converted sheltered opened four days after a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who was in his custody. According to the Minnesota Reformer, the owners of the hotel were already getting ready to evacuate and voluntarily relinquished control to the activists. But the experiment was short lived. The hotel’s owner evicted the new residents on June 9 after a resident’s reported drug overdose.

Some observers think the COVID-19 crisis has brought with it a sharper analysis of the government’s responsibility to provide for its citizens and failure to do so.

“In the 2008 housing crisis, people tended to see their foreclosure as an individual failure, not a political problem,” says Amy Starecheski, director of Columbia University’s oral history program and author of Ours to Lose: When Squatters Became Homeowners in New York City. “As a nation we are rethinking the role of a social safety net and the problems that come from financializing the basic things we need to survive. There’s a real potential for more people to see their housing issues as a systemic failure and I think that opens the door to questioning the sanctity of private property.”

Whether or not there’s a resurgence of squatters’ campaigns, affordable housing consultant Ginger Segel thinks activists have a critical role to play in moving the needle on the affordable housing and homelessness crisis.

“Even if the activists don’t understand all the pieces, there’s no replacement for their willingness to stand up for what’s right and say, ‘We can’t be evicting people and gentrifying them out of their neighborhoods,” says Segel. “You can’t just sit down and from an academic view say our housing system is wrong. Nothing will happen. But people saying ‘we won’t let you do this to my community’—if they have enough community power they can change the policy.”

What activists are missing is that housing supply may be limited because real estate investors buying up properties to flip or rent but not to poor but to turn single family into boarding houses and collect five rent checks instead of one. It would be a fools errand to believe that any of these renters will be poor so who is benifitting other than the investor. I am sure the likes of any wealthy politician will fight tooth and nail not to allow a boarding house nextdoor to their million dollar mansion where five plus bedrooms could accommodate several poor families.