Homes on Montana reservation. Photo credit: Vision Service Adventures, via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Several years ago, I met a young Lakota man who graduated from high school with a full scholarship to college. He lived with his mother, grandmother, and two brothers in a trailer home on a stretch of hardscrabble grazing land on a reservation in South Dakota. The lamp over the dining room table where he studied every night was connected to an outlet in his aunt’s trailer next door by a string of extension cords threaded out the kitchen window. He’d slept on the living room couch since he was 10, when his grandmother moved in. He hoped to become an engineer and help his family build a new home on their land.

Tucked into the sloping hills of a nearby reservation community, my friend and her husband live in a double-wide trailer along with two adult children, those children’s partners, and several grandchildren and foster children. Other family members move in and out of the house periodically.

These precarious housing circumstances are not uncommon in Indian Country, which encompasses American Indian reservations, allotted lands, and Native communities in Alaska and Oklahoma. Indeed, one of the greatest challenges facing tribal leaders today is the dire housing crisis in Native communities across the United States, which as director of the Center for Indian Country Development, I testified to in an oversight hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in October.

There is good news as well—incomes are rising in Native communities, and economic development in Indian Country is starting to make some headway against the results of centuries of isolation and discrimination. There is a strong desire for homeownership among Native households, but a set of obstacles specific to Native lands are getting in the way.

Why Homeownership?

According to a 2017 report from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), about 16 percent of reservation households are overcrowded, compared to 2.2 percent of the general population.

In 2017, HUD estimated that an additional 68,000 housing units are needed in Indian Country. Given the significant overcrowding and high demand, the real need is likely triple that number. The consequences of substandard and inadequate housing are severe and long-term, and include chronic disease, physical injury, and other health problems, as well as harmful effects on childhood development.

There also is a strong and unmet demand for homeownership among Native households in tribal areas: about 75 percent report a strong desire to own their home.

The reason for both sets of circumstances is because Indian Country as a whole is growing, both in population and income. The growing demand for homeownership in Indian Country requires substantial capital investment. It also requires institutional policy reforms that create better incentives for these investments and reduce barriers to lending on reservation lands.

Indian Country is composed of 573 self-governing Native American and Alaska Native communities with reservations that span more than 60 million acres throughout the United States. More than 5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives make up 2 percent of the U.S. population. As a whole, the Native population is growing much faster than the national population: almost 27 percent between the 2000 and 2010 censuses compared to the U.S. rate of 9.7 percent.

During this same period, Native people realized a significant increase in real per capita income: 48 percent (from $9,650 in 1990 to $14,355 in 2018) compared to 9 percent for all Americans. And social and cultural connections to Indian Country remain strong, with a high percentage of tribal citizens (about two thirds) living on or near reservations.

Indian Country is a distinctively important component of the national economy. Collectively, tribes are the 13th largest employer in the U.S., with tribal government gaming and other reservation businesses employing more than 700,000 people, providing jobs with benefits and job training opportunities. Tribal revenue also pumps billions into local economies and contributes significantly to their tax base, and evidence suggests that tribal revenue positively influences reservation households. For example, per capita payments to tribal citizens tended to increase high school graduation rates, extend years of education, decrease arrest rates, and improve civic engagement.

Increased household income also improves economic opportunities in the long run. The Center for Indian Country Development’s (CICD) recent assessment of the Indian Country data in economist Raj Chetty’s Opportunity Atlas shows that Native children growing up on or near a reservation show greater upward mobility. This suggests that reservations may not be the commonly charged predictor of negative economic outcomes, after all, and that investment in communities offers increased odds of healthy and productive lives.

What Is Different About Homeownership in Indian Country?

Despite the growing need for housing, building and financing new homes on most reservations remains a serious challenge. To tribal leaders and mortgage lenders alike, Indian Country has come to signify a legal and bureaucratic maze that makes investment difficult, particularly on trust lands, which are native lands that are held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of tribes. Some trust land is controlled by tribes, which despite being sovereign nations with their own laws, are limited to what can be done with land without approval by the federal government. And some trust land is allotted, meaning title is held by an individual who can sell, gift, or mortgage the land as they see fit with approval from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As such, lengthy and burdensome processes diminish incentives to lend, even with a guarantee from the federal government.

Recent research by the Center for Indian Country Development finds that Native borrowers for homes on reservations are significantly more likely to receive higher priced mortgages, with rates nearly 2 percentage points higher than non-Native borrowers outside the reservation get. In 2016, that meant that the average Native American borrower would pay $107,000 more in interest over a 30-year mortgage.

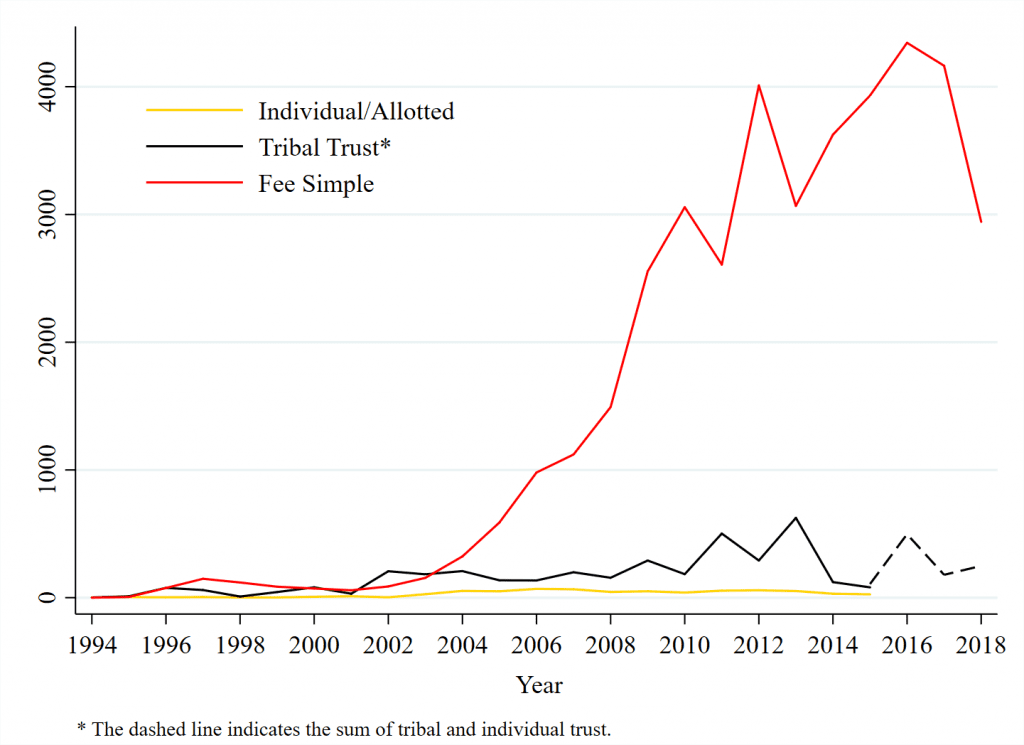

HUD’s Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program has greatly expanded the supply of mortgage credit to Native borrowers, demonstrating both the strong demand for homeownership as well as the creditworthiness of Native borrowers. However, while the HUD program has expanded access to mortgage financing for Native borrowers, most of this capital spending—93 percent of loans in recent years—is on fee land, which is land that is no longer held in trust, but is rather held by an individual who may be Indian or non-Indian.

Since HUD Section 184 loans have strong federal guarantees, the problem is not borrower credit risk. The main barriers to making these loans on trust lands appear to be processing burdens and delays. Tribes holding trust lands (a form of common-interest ownership of property) must issue a lease to the parcel of land to the individual borrower. Called leasehold interest, it operates much like a condominium-type property right, and permits the borrower to use that property interest as collateral. In contrast, fee simple land held by the tribe or an individual can be mortgaged in the same manner as privately owned land outside of the reservation.

Members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs sharply criticized the lack of lending on trust lands in the 184 program in a recent oversight hearing on the housing crisis in Indian Country.

Lenders and federal agencies alike avoid reservation investment for many reasons, but a primary one is the lengthy process for reviewing mortgages on trust lands. Another is the lack of professional resources available to many tribal governments to plan, finance, and implement large-scale housing development.

To overcome these challenges, Indian Country needs a standardized and efficient process for securing mortgages on trust lands. Here are some suggestions for the actions that need to be taken and ways to drive them forward.

Normalize mortgage lending on trust lands by removing bureaucratic impediments and streamlining the land records system. Encumbering trust lands with a mortgage is a lengthy, unstandardized process. To create efficiencies and reduce bureaucratic redundancies, the mortgage lending process for reservation lands should be harmonized and the titling system modernized.

Every mortgage on reservation trust lands requires two title status reports from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the U.S. Department of the Interior. Because trust lands are federal lands, these transactions also require environmental reviews and surveys, adding up to a long and involved process. Moreover, mortgage lending programs across federal agencies are not in sync for supporting transactions on reservations. Agencies such as HUD, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service, and the Veterans Administration each maintain different underwriting procedures, but all must obtain BIA approval. Few lenders are familiar with these processes, resulting in fewer and higher-cost loans. Recognizing these challenges, the BIA released the BIA Mortgage Handbook in 2019 to standardize and streamline the internal process.

Two immediate ways to streamline lending in Indian Country are adoption of a One-Stop Mortgage model throughout federal agencies (BIA, HUD, and USDA) and tribal endorsement of the Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Homeownership (HEARTH) Act of 2012, which Congress passed to encourage tribes to make their own decisions about leasing and managing land development, including environmental reviews and appraisals. Tribes should exercise their authority under the HEARTH Act to create an alternative leasing process to achieve optimal development.

Even with the decades-old hurdles that have existed, tribes are overcoming barriers to lending on their trust lands and creating successful homeownership programs. In the Midwest region, the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin effectively implemented the HEARTH Act and now provides land, leasing, title, and realty services within the boundaries of its 15,000-acre reservation.

In Montana, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation established their own land office to handle much of the BIA’s lease processing and title work. The tribes also own Eagle Bank, created specifically to support mortgage lending to its citizens.

On the high plains, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Housing Authority has an ambitious 400-unit housing project underway with an array of design options and prices offered, mainly using factory-built construction. More than a dozen families moved into these homes this spring.

This is hard work. What is strikingly important about it is that all of these projects are being accomplished under the mantle of tribal self-determination. These are models for success for all tribes.

Reduce the high cost of financing by enhancing incentives for lenders under the popular HUD 184 Loan Guarantee program and creating a secondary market for Indian Country mortgages. Between 2010 and 2017, home mortgage loans made to Native people on reservation lands were three times more likely to be made at a higher rate than loans made to non-Native people for properties nearby. Assuming a standard mortgage term and loan size, Native people on reservations may pay $100,000 more for their homes than an equivalent nearby home owned by a non-Native person. To add insult to injury, many mortgage lenders and secondary market investors have withdrawn significantly from Indian Country since the Great Recession.

One culprit for this disparity is the disproportionate number of loans in Indian Country for manufactured homes. Nearly 30 percent of Native borrower-reservation loans are for manufactured homes, a rate six times higher than non-Native nearby loans. Historically, home loans for manufactured properties have been higher-cost because manufactured homes weren’t categorized as real estate, but personal property, and were considered “chattel” loans until 2012. Because of this longstanding disparity, there is much lost ground to be made up for.

Build developmental infrastructure by improving the capacity of tribal housing programs to pursue housing projects and the capacity of individuals to establish good credit.

The importance of well-trained and responsive BIA and tribal staff cannot be overstated. They are the essential pillars of an efficient lending process in Indian Country. More training and technical support to BIA staff and tribal programs are needed to fully realize the benefits of development tools such as the HEARTH Act and private sector financing. For tribes, grounding a system of housing finance and development requires organizational leadership and a sound legal infrastructure.

What’s Next?

A substantial body of evidence shows the benefits to investing overall in Native communities, but housing must be prioritized.

While the health of a housing market is generally considered a key indicator of overall economic growth, for Indian Country, expanding housing options on trust land would go much further. It would ensure sustainable and self-directed reservation economies. Stable, safe, and affordable homes not only support healthier communities, they enable residents to take better jobs, raise families, and build a vibrant economy.

The Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is tackling these complex issues, where race, place, and economic opportunity often intersect. Through our National Native Homeownership Coalition, we amplify research and policies that better serve the Native population and unlock the potential for homeownership on these lands. Our most recent effort is the Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership, a comprehensive guide to housing development and financing in Indian Country.

Excellent presentation of the situation in Indian Country – Patrice, thank you for this article and for your leadership on behalf of Indian Country!

An additional key asset to note is that USDA Rural Development’s Water and Environmental Program can assist in this work by providing large scale grant/loan combos to finance the water and wastewater (sewer or septic) infrastructure needed to support housing subdivisions.