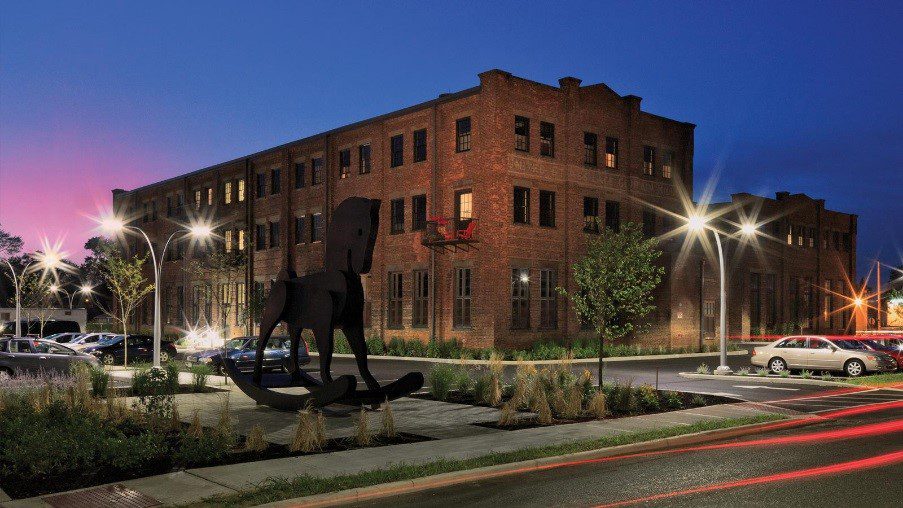

RUPCO rehabilitated the Lace Curtain Mills in Kingston, New York, to create 55 affordable housing units for artists. Photo courtesy of David R. Miller

I’ve worked in rural community and economic development for nearly 30 years. It’s a calling that brings me into almost daily conversation with those who control the levers of community investment—philanthropists, social impact investors, and other community and economic development professionals. Often I’m pitching a project I know will make a difference in the life of a rural community.

Inevitably, the first questions I get are about the size of that impact: How can we scale this up? How many families can be housed, children educated, jobs created, dollars multiplied into the local economy?

I wish I could offer big numbers, perhaps echoing the claim of a certain highly successful hamburger chain—“billions and billions served!” But I can’t.

And it’s a stumbling block that stalls investment in rural places. The demand for big projects promising big-figure results is a litmus test built around an urban context. It’s one that rural communities can never pass. This determined focus on absolute size of outcomes fails to understand what impact looks like in rural places and what I call the “ripple” effect.

For instance, let’s say I’m talking about rural infrastructure improvements. A single highway bridge or tiny municipal wastewater system might not benefit impressively high numbers of users. But these things can make or break the livability of a sparsely populated rural county. Perhaps an investment in Main Street businesses will create, in the most optimistic scenario, 10 jobs. Well that number looks pretty good when compared to a local high school graduating class of only 35. Maybe I’m enthusing about a proposed arts center that won’t enroll hundreds of youth in its workshops or generate high-dollar economic benefits, but for residents of a string of farming and ranching towns, it will be the go-to spot for sharing cultural and artistic expression. By bringing the larger community, county, or region together, it will strengthen the social fabric so critical to rural life.

We must find fresh ways to capture and value the direct and rippling economic, social, and health benefits rural communities experience. If we’re to spur the kinds of community and economic development investments rural America requires, we need a new lens that looks at rural places on their own terms.

The Investment Gap

Rural America is not a monolith of ailing fortunes; nor do all American cities enjoy growth and prosperity. Still, rural investments should be much more than an afterthought to the community and economic development work underway in urban neighborhoods around the country. This is not a “takeaway” game for urban, but rather viewing rural as an added value proposition for investors.

Nearly one-third of rural counties, for example, have poverty rates of 20 percent or higher, versus 15.6 percent in metro counties. Counties with high poverty rates persisting over decades are overwhelmingly rural. Using an index of community wellbeing that includes levels of education, employment, income, housing vacancy, and jobs and business creation, the Economic Innovation Group has documented what it calls “the ruralization of distress,” in other words, the indicators of economic distress increasingly go hand in hand with rurality.

And here’s a trend that’s worrying for the whole country: nonmetropolitan areas helped drive the economic recoveries of the 1990s and early 2000s, but in the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009, half of the country’s growth in new businesses was focused in just 20 big-city counties. In a country with more than 3,000 counties, this heavy reliance on top-performing cities suggests our national economy is less geographically inclusive than it once was, and may prove less resilient in the long run.

The federal government and many states do a fairly good job of steering public investments to rural places, often through set-asides and special programs. For instance, the Internal Revenue Service oversees one of the nation’s most important and competitive resources for affordable housing development, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which includes incentive for building in rural communities. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development mandates that many of its programs set aside a percentage of funding for rural communities. And the U.S. Department of Agriculture focuses the majority of its programs and services to areas that meet a very strict federal definition of rurality based on population density.

The private sector is another matter. Venture capital, for instance, is largely unavailable to the rural entrepreneurs who form the backbone of economic activity in little towns throughout the country. In fact, self-employed proprietors are more prevalent in rural than urban areas, with the most-rural counties boasting 234 per thousand residents, versus 131 per thousand in the most urbanized counties.

Legislation passed in 2017 now gives private-sector actors substantial tax benefits for investing in economically distressed census tracts called Opportunity Zones, including many in rural areas. Not surprisingly, perhaps, this capital has thus far flocked to commercial real estate in and near big cities that already draw investments.

Private philanthropy also tends to marginalize rural places. A 2015 study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that American foundations gave only 6 to 7 percent of grant funds to benefit rural communities—less than half, per capita, of the amount going to metropolitan areas. According to the National Committee for Responsible Philanthropy, between 2010 and 2014, two historically disadvantaged areas of the Deep South—the Mississippi Delta and Alabama’s Black Belt—received only $41 dollars per person in philanthropic resources, compared to $1,966 per capita poured into New York City.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the economics of it, even for investors with purely social aims. I get that higher volume reduces unit costs, whether it’s an apartment building or a job-training program. I understand that clustered investments accelerate economic activity more effectively than isolated ones, and that businesses and other institutions can be more productive when sited near shared resources like transit systems.

But these are urban economics. Density, a massive heaping up of people, knowledge, physical assets, services—this is the nature of cities. And that is part of the balance factor. When they work well, cities propel economic growth not just for their own residents, but also for the country.

The Rural Difference

Rural communities have a different nature. People are organized into small, intricately connected networks. Class sizes are smaller, typically with active ties to the community and high parent engagement. New small businesses are more likely to stay small, and may struggle, but they also tend to persist longer than urban startups. Institutions in general are more informal, without layers of specialization and bureaucracy (because who can afford that?), and they often serve a variety of roles. After the village of Wilson in western New York lost its only bank branch, for example, a local grocery store stepped in as an unofficial change depot, providing coins and singles to other businesses.

Rural places don’t have a dizzying array of local assets, so people rely heavily and invest deeply in the ones they have. For instance the town of Bancroft, Iowa, is shrinking but holding its own, supplied with the basic requisites for quality of life—a few restaurants, a library, a municipal swimming pool, low-income housing options, a Ford dealership, and a medical clinic, among others. Its baseball stadium hosts college-level summer league play and is the town’s pride and joy. Baseball is Bancroft’s thing.

Individuals in rural communities often wear many hats. A town’s mayor may also be an area farmer or rancher. The county’s go-to real estate agent sits on the school board and is married to a clerk in the sheriff’s office. I know that a colleague working on housing in rural Maryland can give me the skinny on exactly how much seniors save on utilities in a new, energy-efficient affordable development. She’s crunched the numbers. Besides which, her mom lives there.

These rural networks of multi-tasking people and multi-purpose assets are fragile. Take away one dynamic leader, a single workhorse community venue, and the loss can be profound, emotionally and economically.

But that goes in the other direction, too. Add one talented special education teacher, one full-service grocer, and the gains may well spread—like ripples in a rain puddle—to the furthest reaches of the community. I know this because I’ve seen it many times. I also know I won’t be able to prove it with big numbers.

A Call to Action

We cannot let requirements for scale and the efficiencies it entails be the stumbling block—the excuse, really—that perpetuates neglect of rural investments. So I’m calling for a new scholarship of rural America.

We need a Jane Jacobs for rural places, someone to observe and document, with care and familiar sympathy, how rural societies and economies actually work. And we need researchers to translate those observations into metrics and tools that capture how community development impacts play out in rural settlements. Projects could be valued for benefits that directly touch an outsized proportion of a small community—market penetration, if you will. We could value them for especially high significance in the lives of individuals and families, a kind of meaning quotient. And we could recognize that some projects, albeit small, supply a basic building block of viable communities anywhere—the critical-access piece.

Rural people weigh these outcomes when choosing the time and place for putting shoulders to the plow. These communities are familiar with setting priorities, doing more with less, and cobbling together their own kinds of efficiencies.

Take the small town of Kingston in upstate New York. Like so many old manufacturing-centered rural towns across America, Kingston’s downtown staple was the U.S. Lace Curtain Mill that once employed hundreds of people and thrummed with industry. But Kingston has suffered population loss and disinvestment for the better part of a century, and the 1903 brick building had been boarded up, abandoned, then under-used as a warehouse for decades.

A gallery at the U.S. Lace Curtain Mill. The transformation of the factory has animated public and private spaces, improved local business viability and public safety, and brought diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired. Photo courtesy of Rural LISC

But locally based community development organization RUPCO saw potential and sought the help of local leaders to make a much needed change. Now, The Lace Mill, which opened in 2015, has come back to life with a different purpose: the factory has been reconstructed into 55 affordable rental units, home to artists.

Conceived as both a housing complex and an economic development effort, the $18 million project is coming into its own as a center of cultural activity as well as providing affordable housing for the burgeoning arts community in the region. In addition to residences, The Lace Mill has several gallery spaces, work studios, and sculpture gardens. Other amenities include state-of-the-art thermal heating and cooling, solar panels on the roof, and energy-efficient lighting.

My organization, Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), the largest community development support corporation in the country, recently dedicated itself to making 20 percent of its overall impacts in rural America by the year 2023. LISC supported The Lace Mill project with grant funding, including predevelopment, capacity building and economic development grants, and with more than $10 million in equity from our affiliate, the National Equity Fund, which included federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, federal historic tax credits, and New York State historic tax credits.

According to Kingston residents and the developers involved, The Lace Mill has already had a profound impact on wellbeing in the area by sparking more tourism and inspiring galleries and restaurants to open in nearby vacant buildings. RUPCO conducted a Community Impact Measurement Survey in 2013 and again in 2016 that showed dramatic improvements in the community. “The survey found statistically significant improvement in perceptions of the quality of life since [The Lace Mill opened],” says Guy Kempe, RUPCO’s vice president of community development. “Residents and visitors now recognize Midtown as a good community to live in.”

As we devise new strategies to pull investments into rural America, we should bear in mind that while yes, renovating an abandoned lace factory in a more urban core might produce a healthier balance sheet, in a place like Kingston, it can represent more—a breath of air, a bid for life, and a call for more action.

“Saving” Rural America

Should we go all-in on urban economies of scale and let distressed, small rural communities dry up and float away? As a lifelong inhabitant of rural New Mexico and Colorado, I’ve been listening carefully to our national conversation about how—or whether—to “save” rural America. Some commentators have gone so far as to suggest that rural folks should move to big cities where the opportunity is, that both they and the national economy would be better off.

Really? Tell that to the people of Selma, Alabama, or Bancroft, Iowa, or the town I call home, Fowler, Colorado. And should we leave a skeleton crew, sprinkled across three-quarters of the county’s landmass, to man the rural operations that provide the nation’s food, water, fuel, and recreation?

Then there’s the future to think about. Tapping some of our most important sources of renewable energy—wind, biomass, solar—requires lots of land, making rural places critical to a green economy. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, in 10 out of 12 Midwestern states, clean energy contributed a greater share of rural jobs than urban ones in 2017. And I can easily imagine a day when driverless cars and digital linkages to work, education, and health care allow more Americans to partake of (and contribute to) urban opportunities while residing in lower-cost, quieter rural places. A 2018 Gallup poll asked Americans where they’d prefer to live given a choice. The top answer: a rural area.

I recall a time when the talk was about saving, or indeed abandoning, America’s cities. Deindustrialization, along with post-war middle-class flight, left some of our greatest metropolises busted, reeling from depopulation, crime, and a growing collection of boarded, abandoned, and decaying properties. This led in some quarters to disaffection with urban life itself, and even a not-so-subtle blaming of city dwellers for the economic disruptions in which they were caught up. After President Gerald Ford balked at providing federal aid to a near-bankrupt New York City in 1975, the hometown Daily News cried foul with its famous headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”

Things change. Forty-four years later the nation is awake to the virtues of our “saved” cities—their density and diversity, walkability, and environmental efficiency.

Rural life has virtues and a culture of its own, qualities in which all Americans can rightly take pride, and possibilities we’ve only begun to imagine. “Drop dead” wasn’t an acceptable answer to urban decay in the 1970s. And it isn’t the right answer to rural areas that can’t produce urban-sized outcomes as a return on investment.

When we understand that, we’ll be in the right frame of mind to stimulate and deploy robust investments in rural America—the kind that will let communities all across the country save themselves.

Great article Suzanne, and thanks Shelterforce for sharing. Where will we find our “Jane Jacobs”? We need to issue this call to action to land grant institutions (and other universities) and start creating our own definition of rural impact. Now.

Thanks for the great article, Suzanne.

“We need a Jane Jacobs for rural places, someone to observe and document, with care and familiar sympathy, how rural societies and economies actually work.”

I believe we already have someone who fits this bill. Wendell Berry, farmer, poet and essayist, has written about exactly these issues for decades. His essays are extremely insightful explorations of the intersection of economics, politics, culture and social capital in rural America. I highly recommend them.

Great article… however, Kingston, NY is not a “small, rural town”; it is a city.