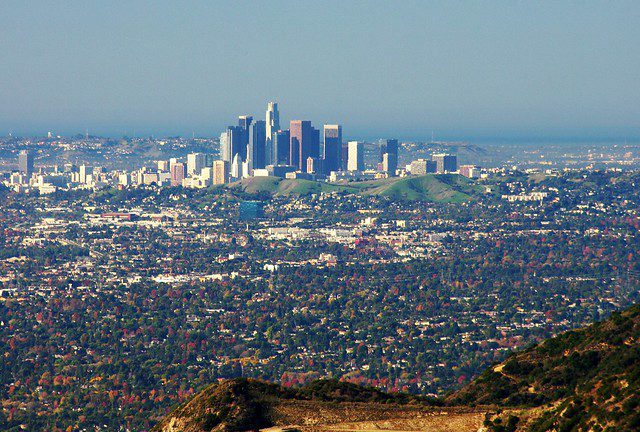

Los Angeles. Photo by Ron Reiring via flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Still in its nascent stages, the Green New Deal sparks debate on the left as to what it should include. Everything appears to be on the table, from massive increases in renewable energy infrastructure to Medicare For All. But one recent development seems especially promising: the growing interest in ensuring housing stands front and center as part of the Green New Deal.

Connecting climate change and affordable housing represents a major opportunity for housing advocates to make much-needed progress toward meeting their goals. But as Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti recently proved, housing will not become a cornerstone of the Green New Deal without a fight.

This spring, Garcetti unveiled a sustainability plan for his city, dubbed “L.A.’s Green New Deal.” The plan includes laudable goals, including limiting fossil fuel use and creating several hundred thousand jobs in the process. But the proposal falls remarkably short on housing, providing a good entry point to flesh out what housing advocates should be demanding of any proposal using the title “Green New Deal.”

Housing and Climate Change

While most media coverage of the Green New Deal’s relationship to housing starts and ends with a commitment to energy efficiency upgrades in buildings, the resolution also explicitly states that addressing the climate crisis will require “providing all people of the United States with affordable, safe, and adequate housing.” Housing’s appearance in the resolution makes sense, as it dovetails perfectly with the Green New Deal’s twin goals: ensuring economic equality and dramatically reducing carbon emissions.

To the former, addressing inequality in the U.S. cannot be done without tackling the nation’s lack of affordable housing. Nearly a third of Americans live in housing unaffordable to them, and there isn’t a single county in the U.S. where a minimum wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment. It’s a problem that can only be addressed head-on through the provision of millions of affordable homes and strong tenant protections like rent control to keep people in their homes.

In terms of reducing carbon emissions, as cities increasingly become less accessible to the poor and working class, low-income workers must travel greater distances to access their jobs, a problem no amount of electric cars will be able to solve, as it often leads to those who use transit the most being pushed out to suburban areas with limited transit infrastructure. Achieving economically diverse density sufficient to meet our goals for carbon reductions will require massive investment in affordable housing.

But these arguments won’t make themselves. Garcetti’s use of the term “Green New Deal” to define L.A.’s sustainability plan shows how, without vigilance, the term will begin to encompass efforts woefully inadequate to solving our twin crises of inequity and climate change.

How Does L.A.’s Green New Deal Stack Up?

In terms of meeting the national Green New Deal’s promise of providing all people “with affordable, safe, and adequate housing,” L.A. must look at its housing needs. According to the most recent Census data, more than half of Los Angeles’s 1.3 million households pay above 30 percent of their income toward rent. The percentage climbs even higher for communities of color.

In fact, L.A. stands as the third-most rent burdened metropolitan area in the nation behind San Diego and Miami. When you add in projections that the city expects to add nearly half a million people by 2035, the enormity of the need for affordable housing to fully provide for its residents begins to come into focus. A recent report from the California Housing Partnership found that Los Angeles County needs 568,255 new affordable units just to satisfy the demand of lower-income renters.

How does Garcetti’s plan seek to address this crisis? L.A.’s Green New Deal sets goals for both market-rate housing development and affordable housing. In terms of market-rate housing, the plan sets a goal of 150,000 new units by 2025 and 275,000 units by 2035. For affordable units, the plan seeks to create or preserve 50,000 income-restricted affordable housing units by 2035.

Both of these goals fall short of the real needs of the city.

The number of market-rate units slated for development would be unlikely to meet the demand of new residents expected to arrive over the next 15 years alone. Not only that, but these new units would be sold for prices at the higher end of the housing market, leaving low- and middle-income in-movers unable to access them, further exacerbating the housing crisis as competition for affordable units increases.

As for those needed affordable units: when more than 700,000 of your residents live in unaffordable housing, offering them 50,000 affordable units seems like a cruel joke. To make matters worse, the affordability of these primarily privately-owned units can expire, and rarely offer deep enough rent subsidies to allow many in low-income neighborhoods to afford them.

A Real Vision for Housing and the Green New Deal

So what should L.A.’s Green New Deal have offered? Here are four principles that would result in a far better outcome, and should guide future efforts to connect housing with the Green New Deal:

- Seize this moment and Think Big. The Green New Deal caught fire because it created a new horizon of what is possible. It’s central addition to the current political debate: provide the left with solutions to our nation’s problems that actually address their severity, whether it’s climate change, health care, or housing. For too long, the solutions offered to the public remain inadequate to their true needs. People long for real solutions, and this moment should be seized to offer them.

- Provide solutions that actually meet the need. L.A.’s Green New Deal should have proposed the construction of enough affordable housing to meet the needs of its residents, not just the number of units that seemed politically possible. In order to truly address climate change, workers need to be able to live where they work, and any solutions should do just that. It’s certainly true that cities suffer from a severe lack of funding for affordable housing from state and federal governments. But even if Garcetti had proposed far more units than the city could build, he could have simply noted that creation of these units remained contingent on state and federal contributions. This would not only be more honest to Los Angelenos, but could help create a groundswell of demand for increased state and federal funding for affordable housing to achieve the proposals laid out in his plan—a groundswell that could also extend to finding tools to access California’s enormous private wealth as well, including some of the $720 billion that the state’s 144 billionaires hold.

- Center equity. The genius of the Green New Deal lies in connecting economic equity to climate change solutions. Housing provides a perfect opportunity to make that connection stronger. By ensuring low-income communities and communities of color can live near their jobs and remain in the neighborhoods in which they currently live, we can take big steps toward addressing climate change and achieving economic equity. By ensuring these communities take the lead in deciding where and what type of housing they need in their neighborhoods—a strategy mentioned nowhere in Garcetti’s Green New Deal – we ensure that the racial inequalities cemented by the original New Deal don’t happen again.

- Try new things. L.A. offers a variety of recycled housing policies to address its affordable housing crisis in its Green New Deal. But given the nature of the crisis and the insufficiency of what’s been tried to so far, why not experiment with bold new ideas, such as those outlined in the recent People’s Policy Project’s report on social housing? Locally-owned, mixed income public housing could be built on city-owned land as a model for how to move forward should federal funding finally arrive.

Los Angeles housing advocates should view the Green New Deal as a gift. It is an opportunity to demand the type of investment in housing required to actually address the crisis we face. It would be an awful mistake to miss this opportunity and back down from this fight.

Bravo Mr. Mills for making the point that too often thinking “Green ” means coming up with solutions such as electric cars or going fully renewable (as was covered in a recent article going for passive energy on new homes will make affordable units less costly to produce than 0 emission homes). By looking to increase density; that alone may reduce more carbon footprints, as well as giving working and poor city dwellers the possibility of living and working in their existing communities while providing more affordable units. There are many ways to do “Green.”