But at the same time, the median house sales price in Detroit was $40,000, easily within reach of anyone at just about any income level who can—a major caveat—qualify for a mortgage. But Detroit is no more typical of the “United States housing market” than San Francisco. In fact, there is no such thing; there are literally hundreds of different markets around the country, defying easy characterization. Not all strong market cities are as expensive as San Francisco; Dallas is a fast-growing city with a strong housing market, yet $199,999 will buy you a new four-bedroom house. There are many more areas like that than there are places like Seattle or Washington, D.C.

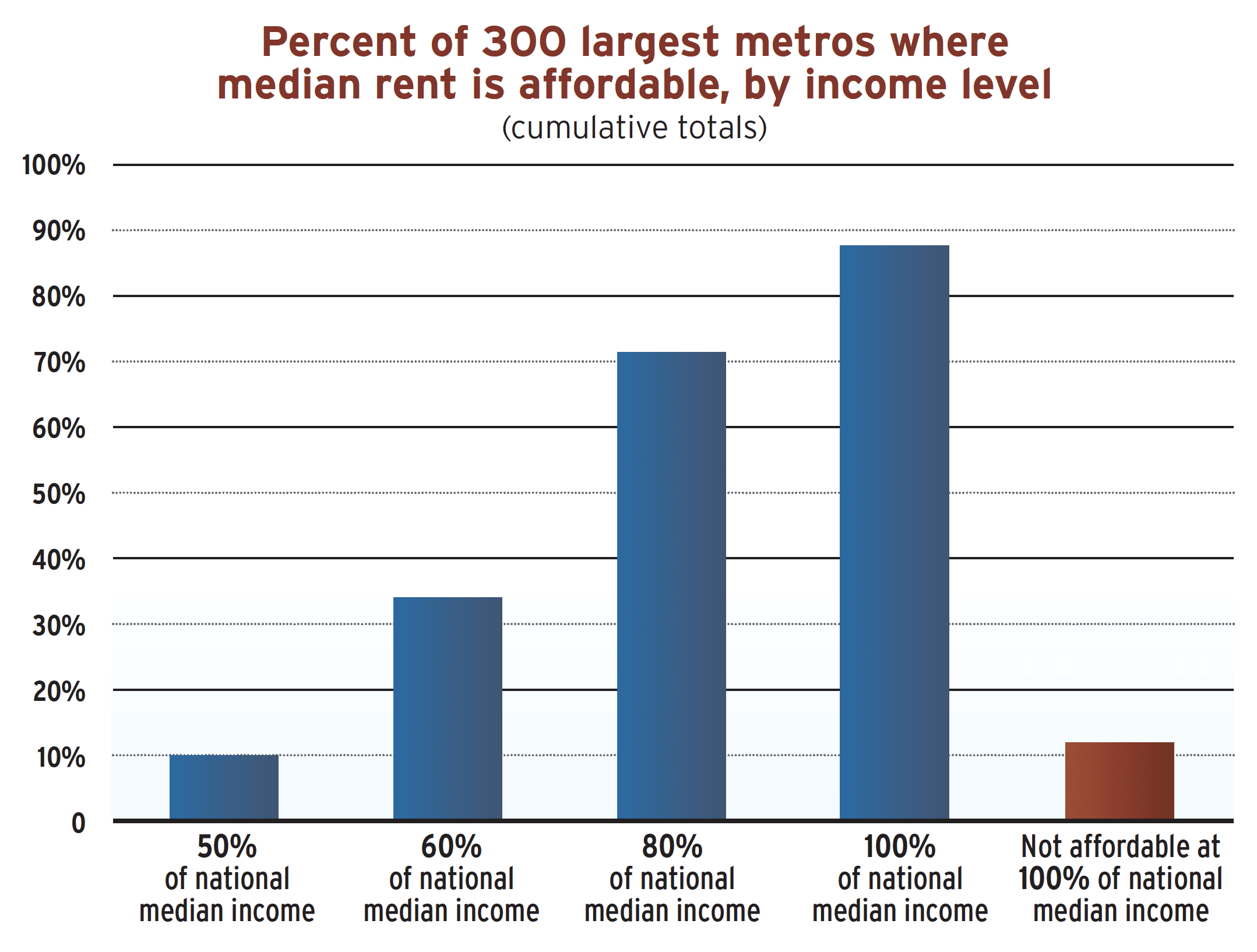

Rents don’t vary as much from city to city as sales prices do, but they still vary quite a bit. But once again, in most parts of the country rents are within the reach of a moderate-income family earning $35,000 or $40,000, while far from affordable to a lot of people who desperately need housing. More than 70 percent of the nation’s 300 largest metropolitan areas (not just central cities) have median rents that are affordable at 80 percent of the national median household income (roughly $60,000) and over one-third have median rents affordable at 60 percent of national median. (This is somewhat misleading because local incomes in areas with very low rents are likely to be below the national median, and those in high-rent areas are likely to be higher than the national median, but the general point still holds.)

When we look at gentrification, we see a similar pattern. At one end, there are a handful of cities where gentrification is spreading across most neighborhoods; and moreover, where high prices mean that once an area gentrifies, few people other than the affluent can still afford to live there. That’s the picture in New York (at least in most of Manhattan and Brooklyn), San Francisco, probably Denver, and a few other places. In these cities, even in the areas that are not being gentrified, prices are still going up, pushed by the citywide price pressure.

[RELATED ARTICLE: What Does ‘Gentrification’ Really Mean?]

If we look at gentrification in other cities, though, we find a very different picture. I’ve studied St. Louis quite a bit in recent years. As older industrial cities go, St. Louis is doing fairly well, but it’s still a relatively poor city, and gentrification is largely limited to a handful of neighborhoods that lie immediately south of the city’s Central Corridor, which is the area where downtown, St. Louis University, the major medical centers, the most upscale neighborhoods, and world-famous Forest Park are all situated. Most of the rest of the city is not changing much, or experiencing an increase in poverty and disinvestment. In a study that compared neighborhood trends in metro St. Louis from 1970 to 2010, the researchers found that “only 5,816 people live in census tracts that transitioned over the 40-year period from high poverty to low poverty, whereas 98,953 live in [census tracts] that became newly poor during that period.” A national study that looked at the 51 metropolitan areas with populations of 1 million or more found the same ratio—roughly 20 to 1.

Second, when a neighborhood gentrifies in a city with relatively low property values like St. Louis, prices rise gradually, but never reach the stratospheric levels found in hot market cities. In a market like St. Louis, where the metro median sales price was $167,600 in late 2018, the pressures on prices—except for one or two super-prime neighborhoods—to rise to hot market levels simply aren’t present. A two-family house shown in move-in condition on a beautiful street in the city’s prime Shaw neighborhood was listed late in 2018 for $215,000.

While sales prices have been rising faster in St. Louis’ gentrifying neighborhoods than in the rest of the city, rents—somewhat surprisingly—have not. Quite a few units in Shaw list for between $800 and $1,000 per month. Paying $900 per month for a two-bedroom unit, in a metro where the HUD Area Median Income (AMI) for a family of four is $76,800, is affordable on its face to a family earning 47 percent of AMI. I will come back to the significance of that number later.

So, if housing prices are low, and gentrification limited in cities like St. Louis and dozens, if not hundreds, of others around the country, does that mean they don’t have an affordable housing problem?

No. Emphatically not. But they have a different affordable housing problem than hot market areas. What does that mean? Bear with me while I run some numbers.

Breaking It Down

If you are a renter who lives in San Jose, California, or Washington, D.C., and you have an annual household income of $40,000, the odds are you’ll be cost-burdened: 87 percent of renters in San Jose and 64 percent of renters in D.C. who earn between $35,000 and $50,000 spend 30 percent or more of their income on shelter. If you’re making the same income but living in St. Louis or Cincinnati, the odds are just as high that you will not be cost-burdened. Only 19 percent of renters in Cincinnati and 23 percent of renters in St. Louis in that income range spend 30 percent or more of their income on shelter.

The picture is very different for tenants earning under $20,000. Just about anywhere in the United States, no matter the housing market, 80 percent or more of all tenants earning under $20,000 will be cost-burdened, and most will be paying 50 percent or more of their income on shelter. In Detroit, it’s 90 percent; in Portland, Oregon, it’s 87 percent; and in Cincinnati, it’s 85 percent.

The absolute numbers show the same pattern. In San Jose—one of the most expensive cities in the United States—there are more cost-burdened renter households earning over $35,000 than under $35,000. But in Cincinnati there are almost 27,000 cost-burdened renter households earning under $20,000, compared to fewer than 3,000 earning over $35,000.

Strong-market cities have what one might call a “middle-class affordability” problem, but for the most part, cities with weaker markets do not. What they do have is an overwhelming problem of affordability—and from all accounts, a housing quality problem as well—affecting their poor and near-poor residents, basically households earning under $20,000 or $25,000 per year. And those households make up a much larger share of the population in a relatively poor city like Cleveland or Milwaukee than in an affluent city like San Francisco. Forty-six percent of all households in Cleveland earn under $25,000 per year, compared to only 18 percent in San Francisco.

That leads to a series of questions. The first one is why don’t rents decline the way sales prices do? There are neighborhoods in Detroit or Cleveland where you can buy a house—not in great shape, perhaps, but livable—for $20,000. You’d spend less than $200 per month on taxes, mortgage, and insurance for that house. But that same house may rent for $700 per month. That doesn’t seem logical, but it is.

While house sale prices will keep going down nearly to zero until they reach their market level—if there is one—rentals work differently. Landlords have to factor in how much they need for maintenance, reserves, repairs, taxes, and some combination of mortgage payments and an acceptable return on the value of their equity. Landlords also factor in their expectations. If they think their property is appreciating, they’ll accept a lower annual rate of return on equity, because they figure they’ll make up for it when they sell the property. But if they think it’s losing value, they’ll look for a higher annual rate of return to make up for the fact that they may not get their money back if they try to sell it down the road. The lower their expectations are, the more they will try to increase their net cash flow, cutting back on maintenance, and even not paying property taxes. So even a landlord who owns a house worth $0 on the market may still need to rent it for $700 to cover their costs and get a sufficient return.

If a landlord can’t get the minimum rent they feel they need to make ends meet, they are not likely to lower the rent below that level, which would mean knowingly losing money. Instead, they’re more likely to walk away.

For a single parent with two kids earning $15,000 per year, $700 per month works out to 56 percent of gross income, a rent burden that puts them in permanent housing insecurity, at constant risk of eviction, doubling up, or homelessness. These are the families that Matt Desmond writes about in his book Evicted, and there are a lot of them. Almost 1 out of every 4 families in Cleveland is a single parent earning less than 1.5 times the poverty level. And they are not the only households in weaker market cities whose low incomes put them at risk—all of these cities have large numbers of single people and smaller numbers of other families who struggle to pay rent every month. On top of the affordability issue, all accounts make clear that a lot of the houses and apartments low-income households do find to rent in these cities are in sorry shape, with unreliable heat and leaky plumbing, mold and mildew, peeling paint, and other conditions that affect their tenants’ health and safety.

We Need Better Options

So is the solution to build more affordable housing? If we’re talking about the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) model, which accounts for almost all of the affordable housing being built in the United States today, the answer is probably no. The fact is that almost all LIHTC units are too expensive for the people who need them most. LIHTC project rents are pegged to be affordable to households at 50 or 60 percent of AMI, depending on which option the developer chooses. In weaker market cities those rents are not only far above what poor or near-poor families can afford, they are usually higher than the median market rent in the same city. In Cincinnati, a new LIHTC two-bedroom apartment affordable at 60 percent AMI can rent for up to $1,057 per month. That is 40 percent above the median market rent for a two-bedroom apartment, and nearly double what the median single parent in Cincinnati can afford if they spend 30 percent of their income on rent.

In most parts of the United States, LIHTC projects charge more than what most families who need better housing can afford. But those families don’t have better options. As a result, when we look at the numbers, we find two startling things: Close to half (43 percent) of all families who live in LIHTC units spend over 30 percent of their gross income for shelter. And of the families who spend 30 percent or less of their income, about two-thirds have project- or tenant-based vouchers (based on my analysis of data in Understanding Whom the LIHTC Serves: Data on Tenants in LIHTC Units as of December 31, 2015). Without vouchers, the great majority of LIHTC tenants would spend more than 40 percent of their income on rent costs. LIHTC projects improve the quality of their residents’ housing, but without vouchers, leave their affordability problems and insecurity unchanged. LIHTC is not a solution.

Moreover, most LIHTC projects are built in high-poverty neighborhoods, areas where sites are available and more CDCs are active, but where total housing demand is not growing. As a result, those projects often cannibalize the existing housing stock; in other words, as new LIHTC units come on line, most of their tenants come from existing rental housing in the same (or similar) neighborhoods, often bringing Housing Choice Vouchers with them. They move out of private market units, or older LIHTC projects, in to areas that already have a large surplus of housing, putting even more units at risk of abandonment.

Production programs by themselves can help meet the needs of struggling middle-class families in San Jose or Seattle, but without increased demand-side or operating subsidies—vouchers, or something similar—we will never meet the needs of the poor and near-poor families who most desperately need a decent place to live and get them the security that comes with knowing that they and their children won’t be out on the street next month.

Creating a universal housing allowance program for those whose incomes are too low to be able to afford modest but decent housing in the private market is far more important to meeting the needs of weaker market communities than increasing production of subsidized housing along LIHTC or similar models. Not to mention that it would be vastly more cost-effective than trying to replace existing habitable private market units with newly built subsidized units costing 10 times or more what it would cost to upgrade the private market units—and still have to provide vouchers or operating subsidies to the new subsidized units.

For me, a universal housing allowance should be the most important national housing policy goal for affordable housing advocates, with nothing else even coming close. And with some serious thinking, we should be able to come up with a model that will both be more cost-effective and work better to improve housing quality and opportunity for poor and near-poor families than the current voucher program.

Clearly, subsidized housing—LIHTC or otherwise—has one big advantage over housing allowances in that it can be permanently affordable housing. I don’t underestimate that. Back in the 1970s places like Seattle or Boston didn’t look that different from St. Louis or Cleveland today. Clearly, what we have—unless there are compelling reasons to the contrary—should be preserved. And this is where the discussion ties back into gentrification, and its relatively gradual, modest course in places like Cleveland. The most new subsidized housing, as well as acquisition of private-market housing for conversion to affordable housing, should happen in those areas where gentrification is taking place. That way, we can not only increase opportunities for low-income people who will move into those units and preserve those opportunities for those who already live in those areas, but also create a long-term pool of affordable units in neighborhoods where the market is likely to continue to rise.

But we also need to acknowledge that the great majority of the affordable housing problems that people in these cities face has little or nothing to do with gentrification, but with poverty and the fundamental imbalance in the low-income housing market.

I would like to know why I signed a lease before rad took over that was a no smoking lease. Now that I have rad my apt is filled with smoke because of Ronald Andersons Chain smoking in apt 609 Ockers Gardens Oakdale 11769 So management “sealed” my apt lol the creeping crud of second hand smoke and vaping residue creeps right through the floor and sheet rock walls of my apt directly above. PLEASE relocate the chain smoker I was here first and he doesn’t care where he gets to chain smoke. The residue is too heavy and stinging me. My health is being assaulted everyday. Please call Mr. Richard Wankle Atty 6315897100 ex220 asap and relocate Ronald Anderson. Thank You for your assistance. Sincerely Mildred Burgos

It’s not often I hear a case against LIHTC development from a housing expert, but I’m intrigued. Yet, I think that, like the rest of your argument, your mileage may vary. In more rapidly growing (but still relatively affordable) cities like San Antonio, LIHTC units can come online and house families living in substandard housing or who have been doubled-up, etc., and not cannibalize existing stock. Similarly, state rules in Texas are designed to ensure LIHTC units are actually located in areas near downtowns, in other areas of opportunity, and not in areas of concentrated poverty–mitigating the issues you mention. But I agree that LIHTC rents are sometimes equivalent to market rents, depending on the submarket, but what these projects offer are units guaranteed available to families with lower incomes (rather than being rented to above-income households looking for cheaper rents), as well as long-term protected affordability as median incomes rise.

I live in a midwestern city similar to St. Louis. You argument is correct that LIHTC units are not always affordable. I disagree with your argument about rental assistance being the solution to the problem. There is still a supply side issue, even for tenants with vouchers. Tenants often rent places that barely meet the minimum Housing Quality Standards if they can find anything at all. In some cases, I wonder how the units passed the inspection. And the rents paid are too high for the market for the units.

Low income housing tax credits are competitive so the requirements could be changed to require that a larger percentage of units be affordable to tenants with very low incomes. Tax credit developers are a resilient group of people and they will find a way to make this work. In addition, rental housing is expensive because property owners see it as a ATM with short term income or an investment that will pay off big later.

We need to look at options like cooperative housing that keep the units under control of the people that live there. Older cooperatives are often some of the most affordable and well maintained housing available.

This would require a massive shift in our housing delivery system and we would have to give up the high level of profits in the tax credit program. Real estate development is a risky business and the availability of more credits would lessen the risk and lower costs. Developers and property owners need to make money but a reasonable rate of return and a smaller piece of the pie for the developers and the owners would leave a bigger bite for the tenants. So let’s rein the developers in a little and get serious about affordability and think about the long term.

I live in St. Louis. Your insights about the rental market are spot on. Rents for basic 2 bedroom apartments in desirable “gentrifying” neighborhoods aren’t significantly higher than crime-ridden, declining neighborhoods.

Example: After a minute of browsing on Zillow, I found a small 2 bedroom unit in desirable Shaw for $825. The only 2 bedroom unit in crime-ridden Wells Goodfellow is $800 (yes, there is only one 2 bedroom unit for rent in WG). Just shows how dysfunctional and limited the rental market is in weak neighborhoods…

From the perspective of Baltimore, this article is on the mark. Allan Mallach deserves thanks for being one of the few “urbanists” who has consistently seen beyond the superstar cities to the Rust Belt, and cautioned that national policy based on the superstar city narratives are a poor fit for most of the country.

I would just add that a reformulation of a supply side program into a housing allowance could negate the multifamily industry’s systemic discrimination against voucher holders (although other forms of discrimination would remain). The lack of rental housing open to voucher families in already well resourced neighborhoods is one big reason that advocates push for LIHTC in these opportunity areas. As it now stands, there is currently a key role for LIHTC to play in producing housing accessible to voucher holders in both gentrified neighborhoods and suburban opportunity areas that have long excluded both subsidized housing production and supply side vouchers. However, instead of seeing this role and incentivizing LIHTC development in opportunity areas, state QAPs usually do the opposite, just reinforcing exclusion.

> If you are a renter who lives in San Jose, California (with) an annual household income of $40,000, the odds are you’ll be cost-burdened. If you’re making the same income but living in St. Louis or Cincinnati, the odds are just as high that you will not be

Wait, no, that’s not OK to assume. We can’t assume same income between markets like that. If your household income is $40k in San Jose or DC, and you get identical job(s) in St. Louis or Cincinnati, your household income is likely lower now, sometimes *significantly* lower.

The reason there are wild disparities in income is not just because “those cities have more poor people”. It’s because the entire market has different sets for pricing, even for middle-class and wealthy people.

A $100k household income in Michigan is going to “feel like” a 50k income when spent in Seattle, even if the per-dollar income stays identical across both markets. And not just due to housing, but due to everything (healthcare, education, daycare, restaurants, etc). These places are technically both denoted in US dollars, but effectively wealthy cities are on their own entire currency than traditional cities, $1 does not equal $1 across these lines, and affordability can not be compared as such. A $210k home in St. Louis is effectively equally as unaffordable as a ~$500k home in Seattle is, or a ~$800k home in the Bay Area is, once you account for that difference.

This is why Gentrification is such a huge issue, even in cities the author claims “don’t have Gentrification”. Weak-market cities like St. Louis and Cincinnati and Detroit have a huge middle-class affordability problem too, once you account for these wild differences in between local currency values and coastal ones.

” That way, we can not only increase opportunities for low-income people who will move into those units and preserve those opportunities for those who already live in those areas”

These two goals are in conflict with each other. There are a couple underlying assumptions with your proposed approach. One, if you are low income, you are always in low income. Two, neighborhoods should be static. Neighborhoods evolve over time, with the ebb and flow of growth, immigration and stagnation, and housing stock and prices should reflect that. It’s what the Latino (ugh. Latinx) folks in the Mission District in San Francisco tend to forget that it was an Irish neighborhood before them.

The problem is that landlords are demanding a ratio of 2 1/2 to 5 times the income to rent ratio for prospective tenants to ensure rent payment and reduce the costs of evictions. Some landlords demand an even higher ratio up to 6 1/2 times income to rent ratio. It is easier for those of middle income to get a mortgage on a house than to rent an apartment. However it is entirely possible for those of minimum wages to either move in with family or friends or be homeless. Those who don’t even make minimum wages can and do wind up in the streets, because public housing and section 8 have long waiting lists.

Interesting piece, but the comments on LIHTC units miss the mark. While the maximum allowable rents on LIHTC units are 50% or 60% AMI, often the rents are much lower, or they are accepting tenants who have Section 8 Vouchers. Roughly 40% of LIHTC units are occupied by Extremely Low Income households. Not all of them are paying 30% of income – some may be paying more because they are in units targeted at somewhat higher income levels. But they are probably paying less rent for higher quality units than would be the case in the private market.

To hell with the percentages and the Analytics. Rents are too high. And not enough really affordable housing. Enough with the studying already. Please build lots and lots of really affordable housing.

I’ve come to feel that real estate websites like Zillow exacerbate these problems. Also house flipping shows. Along with your ideas, more regulations are necessary for the housing market. Landbanking, tax write-offs for “unrentable” units, etc. should be ended or heavily fined. I read somewhere that LA has more empty units than homeless people. That’s psychotic.

Isn’t the biggest problem inadequate and contingent incomes by those on the bottom and increasingly the middle of the income spectrum?As robots do more and more people become interchangeable and replaceable, and all the risks of economic downturn and underemployment are shifted to employees, the costs of being housed become less affordable, and a history of poverty is a barrier as data accumulates on who to avoid. Incentives to build and maintain affordable housing for a growing population is a problem, as is the way education is distributed, but underlying it is the powerful incentive to pay workers amounts that are inadequate?

Well, housing in Dallas has hit the $300,000+ mark. The housing market is toppled w/private investors creating a housing bubble stampeding fair and affordable housing. Strangely, one can purchase an over price newly badly constructed home with buyer incentives but can not afford a pre existing home…More people are living in hotels, cars and boarding homes! 1st there are long waiting list for low income programs 2nd the elderly are having a hard time taking advantage of those programs 3rd I notice that many of the low income housing have substandard living conditions…how they pass inspection is NOT a mystery 4th Tax Reform Act of 1986 is said to give incentives for the utilization of private equity in the development of affordable housing. I guess I am trying to figure out how those incentives boost affordable housing! 5th I am noticing that others are buying homes while Americans (not necessarily low income) are met with much red tape 6th Income/wage lag behind housing cost 7th I also notice that income based apartments keep folk co dependent on the system (folk refuse to work because their rent will go up. These young able bodies need to establish a work ethic and pump taxes into the economy), Young people on housing is keeping the aging population from income based housing! NOT to say young people are not hard working, there are many young people striving to make ends meet…there is a housing crisis in America. Lastly, maybe too much politics when it come to LIHTC?

Wow reading all the comments about American rental and housing crises is extremely interesting.

We have a rent and housing crisis too! House and land prices are skyrocketing, and waiting list for state and social housing is rising. We don’t have a voucher system, but if you are working class or poor, and you are fortunate enough to get social or state housing, you may get rents that don’t exceed 25% of the h/holds weekly income.

Our govt didn’t invest in state and social housing and plan for demographic or natural increase and net migration. We privatise, and deregulated the housing market, and copied the failed model you Americans have. Bearing in mind neoliberalism only caters to a willing buyer meeting up with a willing seller – essentially those on high incomes and wealthy. It doesn’t cater to the poor, working poor, sick and disabled.

No one magic bullet will fix it, but some possible solutions include: The govt build en masse public housing, state and social housing, build em fast, build em cheap, and high quality – healthy, warm, ecofriendly homes. This will reduce inequality, wealth divide, improve health and educational outcomes. Also good housing is a human right, we are not uncivilized cave people.

Reform central banks (Fed if its possible) monetary policy so its remit includes asset price inflation, which includes house and land price inflation.

Cheers

In the US were in an economic crises due to covid-19. Businesses have slow down or shut down. Lost income or very low income to no income, too living in shelters, vehicles, in the street, why is it that home mortgages, apartment rental properties keep rising. Builders keep building multiple family homes. I am seeing new apartments, townhomes, condos, new homes constructions here in georgia counties. With all the encomic lost, it not affordable living. Why is construction continuing when were in a covid-19 crises. Affordable housing is what it should be affordable housing. Get back to fair housing to a single person cost of living, and family members cost of living. To me it is monopolizing the housing industry in some states from middle class to low income single person or families. The US is struggling. Some people are struggling. Greed. Affordable housing is not $20,000 to $25,000 paying $1,400 for rent affordable as a single person. Family income $30,000 to 45,000 paying home mortgage of $2,000. or more is not affordable. It doesn’t make sense for cost of living in an apartment or trying to purchase a home, renting a home keep going up being in the current situation US is in now. The state I am in is fifty miles in the middle, northeast, southwest of Atlanta. Let’s not forget about senior living. Not many locations are being built for seniors 55 to 60’s affordable senior apartments. There is the 40’s to 55 years old approaching. These places should also be income based only…. from social security income to supplemental. Not enough of construction happening at all. Our politicians from government, states, cities, advocates, community organization, and the people we sent to DC senate and congress make new laws and changes fo housing. Keep it simple! That’s my opinion. Thank you.