Photo by David via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Housing affordability appears to be a conundrum. Housing prices tend to be low in communities where job opportunities and/or compensation levels are low. But even relatively “cheap” housing in these communities might not be affordable if household members are unemployed or earning low wages. Contrarily, where job opportunities are more robust in terms of number and compensation levels, housing prices tend to be very high, leaving many households struggling to afford decent housing if they have average or even above-average incomes. A recent article noted that in Silicon Valley, some households with six-figure incomes are having difficulty affording housing.

And so, though most people would consider employment to be a vital factor in determining one’s ability to afford housing, many communities are stuck on a jobs-housing hamster wheel where increasing job opportunities and higher wages appear to be canceled out by a matched increase in housing prices and rents.

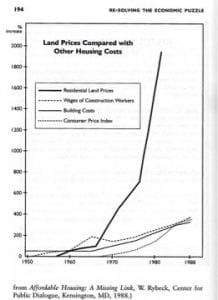

A deeper dive into the cause of high housing prices reveals that it is not the price of lumber, bricks, or labor that accounts for high or low housing prices. The controlling factor most often is the price of land. Some analysts have documented that the 2008 recession, typically reported as the collapse of a “housing bubble,” is more accurately described as the collapse of a “land price bubble.”

Land values represent the totality of surrounding amenities and nuisances (natural and human-made) that make particular locations suitable or unsuitable for a purpose. Typically, public goods and services are provided to facilitate development and to enhance the quality of life within a jurisdiction. If public goods and services are tied to particular locations and are well-designed and well-executed, these areas will rise in value. Municipal dumps, sewage treatment plants, and airports might decrease land values for residential purposes in their immediate vicinity while increasing them elsewhere. And while proximity to an airport might reduce land value for residential purposes, it might enhance land value for certain commercial purposes.

The Value of Land Return

Many economists from widely divergent perspectives agree that returning publicly created land value to the public sector and recycling it for public purposes—known as land value return and recycling or LVRR—could have significant benefits. For example, LVRR encourages more compact development, which is more sustainable both environmentally and fiscally.

Because LVRR is typically overlooked or underutilized as a revenue source, more robust utilization of LVRR could substitute for taxes on privately-created building values. In such cases, LVRR could lead to more real estate development activity resulting in both increased employment and more affordable housing, thereby overcoming the jobs/housing conundrum.

Although most communities utilize LVRR as part of their property tax, it is rare to find communities that apply it robustly. Tax rates vary from place to place, but in many cases, effective tax rates range between 1 and 2 percent of value. The net present value of such a stream of payments in a low-inflation environment is about $10 to $20 for every $100 of publicly-created land values. Thus, many communities are giving away as much as 80 to 90 percent of the land values they create through the provision of public goods and services.

It is the ability of private landowners to appropriate publicly-created land values that is the fuel for land speculation. Land speculation produces nothing of value, but it does tend to artificially constrain the availability of developable land, thereby increasing land prices. Inflated land prices can drive some residents and businesses away from prime locations to more affordable, yet more remote and less productive, neighborhoods. This is part of the impetus for urban sprawl.

Sprawl impairs the environment due to higher transportation/energy requirements and increases paved surfaces. It also impairs municipal budgets by necessitating the duplication of expensive infrastructure systems (streets, water and sewer, schools, etc.). Many suburbs created shortly after WWII are facing fiscal strain because low average household densities combined with significant costs to rehabilitate or replace aging infrastructure require high per household tax revenues.

Getting Off The Hamster Wheel

As noted above, many communities apply an annual property tax to offset such costs. But this tax is also applied against the value of privately-created building values. Assuming that developers expend resources on housing up to the point where a dollar’s expenditure yields only a dollar in additional price, the economic impact of the property tax applied to building values is equivalent to a one-time sales tax of between 10 and 20 percent on the cost of construction labor and materials. This is a significant increase to the cost of production. Basic economics shows that increasing the cost of production reduces production—in this case, housing construction, improvement, and maintenance. This simultaneously reduces employment while increasing housing prices and rents. The property tax applied to building values is also a cost barrier to enhancing the energy-efficiency of new and existing buildings.

A few communities in the United States and around the world have implemented LVRR more robustly than is typical. In many cases, this is accomplished by reducing the property tax rate applied to privately-created building values while increasing the tax rate applied to publicly-created land values. Where this has been implemented, there is evidence that building construction, improvement and maintenance are more robust—meaning more jobs—and that land and housing prices remain more modest than other comparable jurisdictions that utilize a more conventional property tax.

It is important to note that entry-level jobs in building construction, improvement, and maintenance are generally accessible to persons with limited education, but they also provide opportunities to obtain more advanced skills through apprenticeships and on-the-job training. Also, these types of jobs cannot be outsourced overseas. They must exist in the communities where people live and work.

It would seem almost self-evident, therefore, that shifting the property tax off of privately-created building values and onto publicly-created land values could have beneficial consequences—lower building costs and prices, lower land prices, and the increased construction, improvement and maintenance of buildings.

This is not to imply that LVRR alone could return a Rustbelt city to its former industrial vitality. However, whatever potential development demand exists for a particular city, more of that potential can be realized if LVRR is utilized. And utilization of LVRR will help keep land prices more affordable, thereby avoiding the gentrification that occurs in cities where speculation is encouraged and where tax penalties on development allow only the affluent to afford decent housing.

However, despite evidence from implementing jurisdictions that robust use of LVRR links job creation and economic development with more affordable housing prices and rents (thereby resolving the jobs-housing affordability conundrum), robust implementation of LVRR is remarkably rare. Indeed, many citizens and public officials have never heard about LVRR as an option to increase employment while keeping housing prices in check. What about your community?

This is very interesting. I would like to know more about the administrative methods and mechanisms for assessing property tax rates in specific locations according to the principal of LVRR.

Good question. As you know, levying property tax is at least a two-part process. First, the assessors must take an inventory of all properties and estimate the value of both the buildings (if any) and the land for each one. Assuming that your jurisdiction already utilizes a real property tax, this is already taking place. Of course, assessment practices and quality vary widely across the country. Typically, appointed professional assessors are preferable to elected ones. The International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO) can offer educational materials and training. There are also software programs (Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal or CAMA) that can help improve assessment accuracy and uniformity. Bottom Line: Real property assessments are a reporting function that should be carried out regularly by trained professionals.

Second, regardless of assessments, no tax is due unless and until a TAX RATE is applied to the assessments. Typically, the same rate is applied to the assessed value of both the land and the building. As suggested in the article above, it is more equitable and productive to reduce the tax rate applied to privately-created building values and to increase the tax rate applied to publicly-created land values. In many states, legislation would be required to allow individual communities to tax land and buildings at separate rates. (I have already drafted model legislation in this regard.)

Once state-level authorizing legislation is in place, a community must enact enabling legislation. (I have model legislation for this as well.) The process of moving away from the status quo to an improved LVRR system should be performed gradually. But the desired ultimate tax rate differential should be well publicized even if yearly tax rate changes are initially small. This allows property owners to re-orient their behavior to take advantage of the new incentives without being subject to windfalls or wipe-outs.

Typically, a community would want to raise the same amount of revenue under the new system as it did under the old system. I have performed such calculations in the past and would be happy to work with your community’s office of tax and revenue to use actual assessment data to develop a revenue-neutral transformation that would be politically acceptable to your community. Feel free to contact me via my website.

More evidence that rents are tied to land values. Rents in parts of Brooklyn New York recently declined due to a planned 15-month shutdown of the L Train to Manhattan (to repair hurricane damage). Parts of Brooklyn that are not as dependent on the L Train for access to Manhattan saw little or no decline in rents. See https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/gy3ev3/rent-in-brooklyn-is-finally-kind-of-sort-of-going-down-a-little-thanks-to-the-l-train-shutdown