People live in communities because natural and human-made resources make them productive places to live, work, and play. Because geographically based resources are gifts of nature or created by the community, community control makes sense. Public parks, community land trusts (CLTs), and zoning are common ways to achieve “community control.” But there is another way—land value return and recycling.

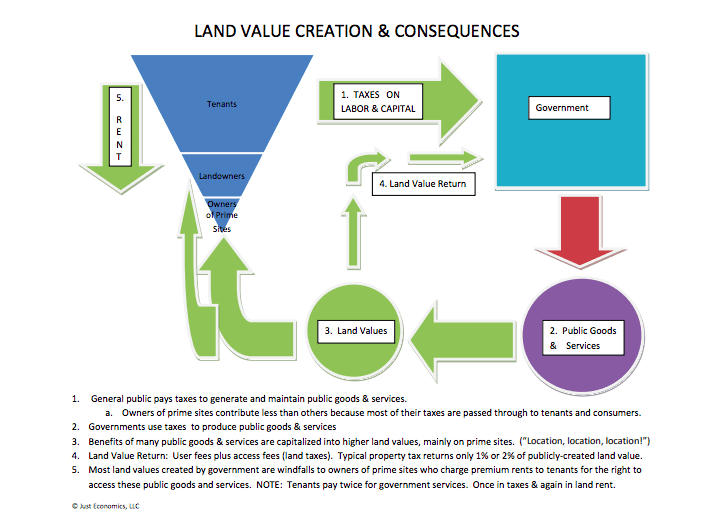

Land values reflect the totality of all nearby amenities (and nuisances) that make a particular place suitable (or unsuitable) for residential, commercial, or industrial purposes. Today, most infrastructure-created land value becomes a windfall to those who own the best-served land. Thus, most members of the public end up paying twice for infrastructure. First, they pay taxes to create or improve infrastructure. Second, if they want to locate their home or business nearby, they must pay a landowner a premium rent or price to get access to the infrastructure that their taxes created.

Landowner appropriation of publicly created land value is the fuel behind land speculation. Speculation creates nothing of value. But, it constrains the availability of developable land, thereby inflating land prices. Inflated land prices drive residents and businesses away from the most valuable and productive land toward cheaper, but more remote and less productive, sites. This creates sprawl, which harms the environment, requires costly infrastructure duplication, and reduces economic productivity. Speculation also creates land price bubbles which impair the economy.

Land Value Return and Recycling

Most communities practice some form of land value return and recycling (LVRR). That portion of the property tax applied to land values returns natural and publicly created values to the public sector where they can be recycled to help make infrastructure financially self-sustaining.

But most communities capture only a small fraction of the land value that they create. In most communities, property tax rates range between 1 and 2 percent of market value. If this stream of payments were collapsed into a single, one-time payment, it would be worth about $10 to $20 for every $100 of publicly created land value. Thus, most communities are giving away 80 to 90 percent of the land value they create. The best-served land in most communities is owned by wealthy individuals and corporations. So most communities collect taxes from everyone and, by providing infrastructure, enrich those who are already affluent. This is part of the reason for growing inequality.

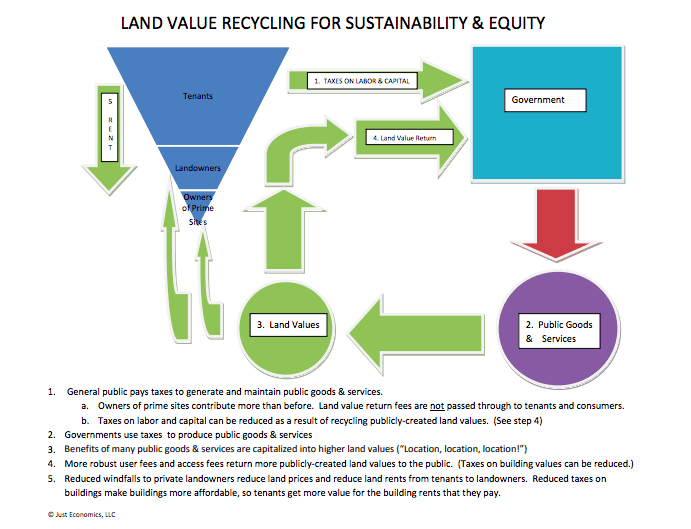

Some communities apply LVRR more vigorously. They obtain the following results:

- Land prices are more affordable. Land prices reflect the benefits that people expect to receive from owning it. Taxing land values more heavily reduces ownership benefits, thereby reducing what prospective purchasers will pay.

- Reduced taxes on privately created building values, reducing the cost to construct, improve, and maintain buildings. (Good for residents and businesses.)

- Comprehensible, justifiable, and equitable taxes. Landowners pay in proportion to the public benefits received.

- Less Sprawl. Taxes are high where land values are high, inducing development on these sites to generate income from which to pay the tax. High-value sites are near existing infrastructure amenities (e.g., parks, transit, etc.), which is where we want development to occur. Increasing development near existing infrastructure reduces development pressure in outlying areas, reducing sprawl. Compact cities require less infrastructure. They are more sustainable both environmentally and fiscally.

You make some good points. Obviously we have a capitalist economy which means it is normal for land value to enrich private parties. But you are right that public investment should produce more public benefit. I do think that many of these investments yield better public returns than you suggest. I agree RE taxes are typically 1-2 percent of value but if you capitalize that stream I think it works out to more than the 10-20 percent you say. There are supposed to be other public benefits too in the form of jobs, housing, exciting places to go, etc. that make our communities desirable but it doesn’t always work out. How can we get a better ROI? Unfortunately we have to start with the reality we have—private wealth in exchange for risk-taking. We also need to acknowledge that in places like the Midwest and South it’s harder to make the numbers work in community development without public investments that may never be paid back.

You say that it’s normal for rising land values to enrich private parties. Segregation used to be normal, but that didn’t make it right.

You note that capitalism rewards risk taking. It is important to understand that there are different types of risk — and not all types of risk deserve a reward. Under capitalism, many people take the risk of investing in hopes of making a good return on investment. But buying and selling land (while risky), is NOT an “investment” in the economic sense. An “economic investment” is forgoing current consumption, and using this saving to create something new that might generate a return. When people buy and sell land, they create nothing new and nothing of value. In our every-day language, some refer to this as “real estate investing.” But in reality, it is simple gambling. And the gambling is based on the ability to appropriate the value of other people’s work. (The value of land is based upon what the community does and not on the efforts of an individual landowner.) People who gamble take a risk. But I don’t think highly of a system that rewards people for gambling. I want a system that rewards people for making things that might have value. Rewarding land speculation leads to inflated land prices that burden most residents and businesses.

I have no problem with people profiting from true investment. That’s why I recommend reducing the tax applied to privately-created building values. Constructing, improving and maintaining buildings are real economic investments. They create something of value in hopes of making a return.

As for the capitalization of property taxes, it depends upon the capitalization rate used. This rate varies depending upon the rate of inflation and the measure of risk. However, if the public sector makes a $100 investment that increases land value by $100 for 100 years and the rate of return is $1 (1%) per year and the discount rate is 1%, the net present value of the investment is -$90.53 and the present value of the $1 annual payments is $9.47. If the discount rate (inflation) rises to 3%, then the net present value of the investment is -$91.47 and the present value of the $1 annual payments is $8.53. Thus, the present value of the 1% property tax payment is slightly less than 10% of the $100 investment in a low-inflation environment and even less if inflation becomes more robust.

I’m not on Twitter. But somebody who is, read the article and asks: “How is it that land value return fees are not (i.e. prevented from being) passed on to tenants and consumers?”

Great question! (Maybe somebody who’s on twitter can pass this along to the person who asked.)

We take it for granted that most taxes and fees are “passed on” to the ultimate consumers of the thing or service that is taxed. It certainly seems true from our experience. But this is not automatic. It results from a process. Mary and I both own shoe stores located next door to each other. As a result of existing market and regulatory factors, we are selling our shoes for $10 per pair. Today, our community imposes a $1 per pair tax on shoe sales. Mary and I immediately try to raise our shoe prices to $11 to maintain our income. But our customers aren’t willing to pay more for shoes simply because the tax has been imposed. So, initially, the price of shoes remains at $10 and Mary and I must eat the tax.

Now Mary is a very competent business woman. She’s frugal and has good control over her inventory. I’m not so careful. All my receipts are in a shoe box and I’m a bit wasteful in my practices. Before the $1 tax is imposed, Mary is making a profit and I’m just barely making ends meet. As a result of eating the tax, I go out of business after a few weeks. Some of my customers come by and see that my store is closed. So they go into Mary’s store. They see a pair of shoes they want and just before they get to them, another customer takes them off the shelf and the disappointed customer says to Mary, “Wait! I’ll pay more for those shoes!”

In other words, the pass-through of the tax is a process. Initially, prices don’t change. Marginal producers go out of business. Later, as a result of reduced supply, consumers bid up the price of the thing that is taxed.

Land is NOT produced. There is no less land after it is taxed than there was before. So there is no reduction in the supply of land to induce any price increase after land is taxed. Furthermore, as mentioned in the article, land speculation creates an artificial scarcity of land available for development at any give time. Making land speculation more expensive causes some speculators to put their land on the market. This reduction in artificial scarcity should create downward pressure on land prices. Finally, what people pay for land is based on the expectation of benefits from ownership. Taxing land values reduces the benefits of ownership. Thus, returning land value to the public sector that creates it causes the price of land to go down.

The article suggests that the property tax be transformed into a public services access fee by reducing the tax rate applied to privately-created building values and increasing the tax rate on publicly-created land values. If this were implemented in a revenue-neutral way (raising the same revenue as the traditional property tax), properties that had the typical building-value-to-land-value ratio would pay the same tax under the new system as under the old. (Of course, they wouldn’t be penalized as much for maintaining or improving their building in the future.) Properties with a higher-than-average building-value-to-land-value ratio would see their taxes decline. Properties with a lower-than-average building-value-to-land-value ratio would see taxes rise.

What if such a property (with relatively low building value) was rented to commercial tenants with a “tripple net” lease? (Such leases requires tenants to pay all applicable taxes and fees.) Initially, rents would rise for these tenants. However, as the new tax incentives would promote new development, new space would become available in buildings with lower taxes and they would have an opportunity to move into those buildings. Owners of buildings with low building-value-to-land-value ratios would loose tenants. They would have to reduce rents and/or redevelop their buildings to remain competitive.

So, depending on the prevailing commercial vacancy rate in a community, there might be a time lapse between when rents in some buildings would rise and when lower rents in other buildings might become available. In such cases, commercial rent control or other short-term stop-gap measure might be appropriate.

Good question. Sorry that my response is too long for Twitter.

Thanks, Rick. We shared your comment with the Twitter user who asked the question.

Thanks Lillian for letting me know about the reply (I’m the twitter person that asked the question).

Thanks Rick for the original article and for the reply. I’m an advocate for LVT because I think it’s sensible. Everything you explained here was sensible too.

I do, however, want to say that I’m not a fan of ‘revenue neutral’ tax modification in-and-of-itself. It’s nice to have, but I’d also want to increase taxes on land in order to decrease wage taxes.

Also, get on twitter so you can point to the clear wisdom that you write. Trust me, the twitterverse needs you.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research just pointed out that over the past year, core inflation (EXCLUDING rent) was up only 1.5%. However, INCLUDING rents, core inflation increased by 2.4%. See https://cepr.net/data-bytes/prices-bytes/prices-2018-08 .

We are on a jobs-housing hamster wheel. In rust-belt cities, housing costs appear cheap. But, if you’re out of a job, even a cheap house can be unaffordable. In places where jobs and wages are more robust, housing prices are still out of reach. In Silicon Valley, households with 6-figure incomes are having trouble finding housing they can afford. Thus, plentiful jobs with good wages DON’T SOLVE THE HOUSING AFFORDABILITY CRISIS.

Land speculation is a big part of the problem. Eliminating land speculation is not the only solution. But unless we do this, the other solutions don’t work or might even be counter-productive.