The Federación Uruguaya de Cooperativas de Vivienda por Ayuda Mutua (FUCVAM) is composed of more than 500 mutual-aid cooperatives. Above, Mesa 5 cooperative members explain how the housing complex’s services and maintenance work. Photo by Jerónimo Díaz via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Every day thousands of parents in the U.S. are forced to take apart their children’s bedrooms and uproot their kids from friends, communities, schools, and neighborhoods. Teachers, domestic workers, and nurses are pushed miles and miles outside of the communities they serve, by evictions and out-of-control rent increases. Every day thousands of our elders are pushed out of the safety and security of their homes, which allowed them to live in dignity, see longtime friends, and access care. Every night millions of people are forced to sleep in their cars, under bridges, and on friends’ couches because they simply cannot afford to pay the rising cost of having a roof over their heads.

We are in the midst of a crisis driven by a U.S. housing system that has shown it is incapable of providing safe, affordable, and permanent homes to families, elders, and children. The current model—rooted in the idea that land and homes are products that can be bought, sold, and traded to make profit for corporate landlords, real estate corporations, and Wall Street hedge funds—has driven decades of rapid gentrification, multiple subprime lending crises, the U.S. foreclosure crisis and economic collapse, and now an out-of-control rental housing market. Along with federal and city policies that have repeatedly allowed for the under-resourcing, exploitation, and displacement of Black communities and communities of color, our current housing system has fueled the ever-growing racial wealth gap and dispossession of communities of color across the country.

Millions of families endure the pain of losing their homes or being left on the street, and cities struggle with a housing crisis that is tearing apart neighborhoods, cultures, and histories, but this doesn’t have to be: There are scalable land and housing models that can serve as a blueprint for justice and homes for our communities. Two of these models exist in the United States: limited-equity cooperatives (LECs) and community land trusts (CLTs). Two exist outside of the U.S.: the tenement syndicate model, from Germany, and mutual-aid housing cooperatives, from Latin America.

In Communities Over Commodities: People-Driven Alternatives to an Unjust Housing System, a report published by the Homes For all Campaign of Right To The City Alliance, this crisis is addressed head-on by exploring alternative, beyond-market housing models that center community control and decommodified land and housing for long-term, affordable, inclusive, healthy, and sustainable homes.

In the report, a new set of “Just Housing Principles” serve as a guide that we hope will become ingrained within housing and development policies if our system is to be truly just and provide affordable and dignified homes for all. The principles—community control, affordability, inclusivity, permanence, and health and sustainability— are used in the form of an index to analyze and assess the various housing models discussed in the report. Each of the four models aligns with the vision that housing is a human right, not a commodity to maximize profits. Each relies on removing land and housing from the speculative market and placing it under the control of those who live and are part of the community. And each in its own way enacts the five principles.

Limited-Equity Cooperatives and Community Land Trusts

The first two models, LECs and CLTs, work by applying the shared-ownership concept of a cooperative to housing.

The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board in New York secured a loan for this 34-unit building in Harlem in 2007. The residence is a limited-equity cooperative that is part of the Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) program. Photo courtesy of UHAB

In LECs, as in all housing cooperatives, member-residents jointly own their building, have democratic control, and benefit socially and economically from living in and owning the cooperative. Households are shareholders of a corporation that owns the LEC, and they have exclusive use of the unit, with rights to occupancy secured through a proprietary lease that protects tenants against unjust eviction, and includes resale restrictions. Affordability protections for early LECs typically lasted for 30 to 40 years, but recently, there have been ongoing conversations to ensure that LECs remain affordable for a longer period of time.

CLTs are a dual-ownership housing model that separates ownership of the land from ownership of the home. A CLT acquires and retains parcels of land, taking them off the market and placing them under community control through a nonprofit organization, which holds the land in trust. Residences can be owned by individual homeowners who hold titles to houses on that land or may be multi-use or rental projects owned by the tenants as a cooperative or by a private landlord.

The Tenement Trust

The Tenement Trust model operates under guiding principles of democratic decision-making and autonomy. By autonomy, we mean the model aims to create housing that is self-organized by residents and is both outside of the private market and not government-run.

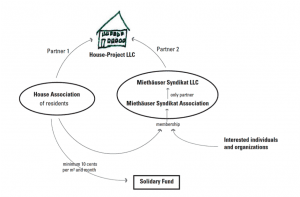

An organization chart of a hybrid dual-ownership model that is best exemplified by a German network founded in the 1990s: The Mietshäuser Syndikat. Courtesy of Malcolm Torrejón Chu

Its key feature is a hybrid dual-ownership model—best exemplified by a German network founded in the 1990s. The Mietshäuser Syndikat has two main organizational components: individual house-projects (mostly large, previously underutilized buildings that have been converted into multi-unit apartment complexes) and the Syndicate—a support and supervisory body. Each individual house-project has an accompanying House LLC that holds the ownership title of the house, and the Syndicate association, which is made up of all the house-projects, has its own LLC called Syndicate LLC.

Within each House LLC are two stakeholders: the housing association (which includes all the members of the individual house-projects), and the Syndicate LLC. Thus, ownership of the property is split and does not belong to either the tenants (individually or collectively) or the Syndicate. By giving the House LLC ownership of the title to the house, neither the tenants nor the Syndicate LLC directly own the house, and both stakeholders in turn have equal voting rights—that is, each party gets one vote—particularly regarding the potential resale of the house-project. The Syndicate LLC that comprises all the house-projects ensures that each project remains permanently affordable and guard against speculation and commodification of the properties. In the German Syndicate, there are 128 housing projects, each with 10 to 20 units.

Mutual-Aid Housing Cooperatives

Mutual-aid housing cooperatives innovate by relying on self-construction. Mutual-aid housing cooperatives were founded on the principle that housing is not a market commodity, but rather a communal public asset. In a mutual-aid housing cooperative, a group of families forms a cooperative to collectively own and manage land and participate in the process of construction of housing. If the land is purchased (rather than granted), the group funds the land purchase and construction through a collective loan that minimizes individual risk. One of the distinguishing aspects of mutual-aid cooperativism is the emphasis put on the participation of the whole family in the constructive process, including responsibility and authority given to women, youth, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

Volunteer resident labor, or “sweat equity,” cuts the construction costs of housing and facilities.

Photo by Jerónimo Díaz via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Unlike the other three alternative housing models, in mutual-aid housing cooperatives, there is no individual ownership or share, and residents cannot sell, rent, or sublet any part of the cooperative, or use it for commercial purposes. Most mutual-aid housing cooperatives strive to not only provide affordable housing, but also to foster self-management and political mobilization of the community.

The oldest and largest federation of mutual-aid housing cooperatives can be found in Uruguay: the Federación Uruguaya de Cooperativas de Vivienda por Ayuda Mutua (FUCVAM). Composed of more than 500 housing cooperatives, it has been in existence for more than 50 years and represents more than 25,000 families. The federation works primarily to organize, support, and train mutual-aid housing cooperatives, and to support the expansion of the model to other countries throughout Latin America.

The FUCVAM model ensures affordability by securing state loans to initiate and support new cooperatives, reduces costs through volunteer resident labor or “sweat equity” that cuts the construction costs of housing and other facilities such as health clinics.

Communities over Commodities contends that each of these four models significantly outpaces the current U.S. housing model’s ability to meet the five just housing principles.

All the alternative land and housing models have explicit principles, structures, and practices that speak to the centrality of community control. Three common components—community ownership, democratic control, and training and education—support the empowerment of residents to cooperatively create and shape their communities and cities and in so doing to thrive.

Each model also takes explicit steps that enable affordability: 1) removal of land and housing from the speculative market; 2) elimination or great restriction of individual and/or corporate profit; pooling of resident resources and any public financing/subsidies to the land and structures such that if someone leaves, the housing remains affordable; 3) residents’ support of one another through the creation, pooling, and sharing of resources and allocation of resources based on each resident’s financial capacity.

Each model deeply values, and seeks to ensure, permanent affordability, allowing residents to live without the ever-present threat of eviction or displacement. Permanence often means residents permanently living in their home thanks to the lasting affordability and the supportive and caring community. But residents can and do sometimes leave. In all the models, what does not leave when a family leaves—and what remains permanently affordable—are the homes. Each model in its own way ensures that the housing, regardless of who lives in it, is affordable.

All the models serve and are inclusive of marginalized populations, though not necessarily all groups of marginalized people. Even so, the models are far more inclusive than the market-based housing around them. All the models are inclusive to low-income people and those living in poverty because of the affordability. Many LECs and CLTs are founded by and made up of immigrants and people of color. Some CLTs are explicit about ensuring representation of people of color. Tenement syndicates are well established in some LGBTQ communities. Mutual-aid cooperatives reach out to and engage women, young people, and those with disabilities. These mutual-aid cooperatives also strive for gender equality by requiring equal roles for women and men in construction work.

Getting These Models to Scale

Four models represent promising alternative solutions to the current unjust housing system. Implementing them to scale in the U.S. will require a shift in municipal, state, and federal housing policy to support expansion and protect them from market pressures.

The shift in policy involves approaches that meet five housing criteria:

- ease and protect access to land and buildings;

- offer direct and indirect subsidies;

- create supportive regulatory or legislative environments;

- prevent displacement;

- address harm previous policies caused.

These policy recommendations do not name one particular alternative model but rather ensure, regardless of which particular model is used, that the five housing criteria are addressed. Housing and development that meet the criteria are termed “PAD,” for “permanently affordable and democratic.” PAD developments rate highly in each of the five housing principles and address the needs of those most in need. To this end, each of the policy recommendations specifically names PAD housing or development as the desired and preferred outcome.

Organizing and Movement Building

While government investment in social and public housing is a large part of the answer, we are clear that to transform the current housing system requires us to build a movement for PAD housing. And this movement is not limited to housing: the movement for housing justice is deeply connected to other movements for justice. A growing number of people across race and class face difficulties with housing under the current model, but housing insecurity disproportionately affects low-income, people of color, indigenous peoples, women, LGBTQ people, and immigrant communities. Housing is also deeply connected to environmental justice. In the fight for just housing, there exists a possibility of alignment and connection between all these communities and struggles.es in Barrio Sur, Uruguay. For decades, the federation has promoted a housing model based on self-management, mutual aid, and collective ownership.

Comments