Photo by Patrick Feller via flickr, CC BY 2.0

The first time Tiffany Fowler appeared in Chicago’s Cook County eviction court in March, she told the judge that the property management company’s attempt to evict her was unfair: She believed the company was retaliating after she lodged complaints about having no heat all winter.

The judge agreed that the eviction appeared bogus and told Fowler to come back with the city inspection reports that found illegally low temperatures in her Woodlawn apartment, which her friends called “The Ice Castle.”

But when Fowler returned to court the next week, there was a different judge on the bench who had no interest in her documents. When she signed a form drafted by the property management company’s attorney, Fowler thought she was agreeing to negotiate a settlement at a later date.

She told the judge she did not trust what the management company would do and needed to consult with a lawyer. The judge stamped the order anyway—an order that turned out to be an agreement forcing Fowler to pay a portion of her remaining rent and vacate her apartment by the end of the month. Legal aid workers with the Lawyers’ Committee on Better Housing and the Metropolitan Tenants Organization subsequently told her there was no way to appeal because no record exists of her conversation with the judge.

“I got played by a system,” Fowler, 36, said. “I know people of color get treated wrong, but I felt like I was automatically judged, like I was some poor little Black girl, like you just know I don’t have money.”

In a court division where a family can lose their home after a two-minute trial and only 12 percent of tenants have lawyers, the lack of court transcripts—with no court reporters or digital recording equipment since 2004—has serious repercussions, largely preventing effective appeals of eviction rulings and making it nearly impossible to hold judges accountable.

Now, more than two years after the Cook County Circuit Court’s Chief Judge Timothy C. Evans requested five digital court-reporting units for its eviction courtrooms, the Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts (AOIC) says it is moving forward with a plan to install digital recording equipment in those courts. But when that will happen remains uncertain.

The AOIC planned to purchase recording equipment by June 30, spokesperson Chris Bonjean stated in an email. However, Bonjean said he did not “have a timetable” for when the courtrooms would be connected to the AOIC’s existing building communications center and recording can begin, because cabling to connect the equipment between the building’s floors had “run into an issue with asbestos.”

Advocates want it done. “If indeed the AOIC is moving forward with purchasing and installing this court recording equipment, we’re very, very pleased,” said Malcolm Rich, executive director of Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice, which has been working with a network of community and legal organizations to advocate for the implementation of recording equipment for almost two years.

“Our main concern is that this injustice be corrected so that all parties in these eviction courts have the option and the ability to appeal, and that the judges in the circuit court are being held to be both transparent and accountable.”

Bonjean said it has taken this long to begin implementing a plan in part because the state was without a budget for two years, and because the Illinois Supreme Court’s general fund, from which court recording projects are funded, has had no increase in funding since fiscal year 2014.

It was not clear why this would explain the delay, given that the equipment is supposed to be purchased during the current fiscal year, before any possible 2019 funding increase. When asked about it, Bonjean said, “The types and numbers of projects vary each year.”

“Chief Judge Evans defers to the AOIC’s timeline to complete the project and will work with any timelines the AOIC suggests or requires,” wrote Pat Milhizer, Evans’s spokesperson, in an emailed statement. Evans’s December 2015 request for recording in Cook County eviction court set the current AOIC process in motion.

In July 2016 after discussions with Evans, Chicago Appleseed, and eight other groups, including Cabrini Green Legal Aid, LAF (formerly the Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago), and the John Marshall Law School, wrote to the AOIC asking the Illinois Supreme Court to fund court recording systems in all Cook County courtrooms without court reporters or recording, with eviction court as a priority.

The Appleseed Fund wrote, “The issues stemming from a lack of court reporters are particularly salient in eviction courts, where many tenants lack the financial means for legal representation.” Cook County had an average of about 30 evictions a day in 2016, according to court records obtained by The Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

By October 2017, advocacy groups had seen little progress. At the time, Rich wrote to Evans: “It appears that this once-promising initiative seems to have stalled, despite the agreement in principle from your office and the AOIC that such recording equipment is badly needed . . . I hope we can work together to get this important reform accomplished.”

Now that plans are in motion, Rich expressed interest in learning the timeline. “We do understand that there are budgetary issues and there are logistics issues, but we hope that the AOIC and the circuit court will be able to let the community know when this is going to happen,” Rich told Injustice Watch last week. “Moving forward with the purchase and installation of court recording equipment will be righting a hidden injustice that’s been in our eviction courts for too long.”

No Transcript of Eviction Court Proceedings? Good Luck Appealing

Fowler came to eviction court at the Daley Center with advantages over many tenants: a flexible work schedule that allowed her time to come to court, enough money to pay her rent, and experience handling administrative matters from her career in marketing and as an executive assistant. But like most other tenants, she had no lawyer and there was no court reporter—no advocate, and no proof that the judge had ignored her concerns.

Legal aid workers say cases like Fowler’s occur frequently, especially given the speed of eviction court proceedings and the fact that so many litigants have no representation. A March 2018 report from the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing (LCBH) found that only 12 percent of tenants have attorneys while 81 percent of landlords are represented, and that final judgments are frequently decided only minutes into the first appearance in court; an older report that measured eviction trial timing found the average trial was one minute and 44 seconds.

“We have clients that might come to us after a judgment has been rendered in court, and they’ll tell us that they tried to raise a particular issue, they tried to ask for a jury to hear the case, something happened that they felt was unjust . . . and there’s no way for us to be able to confirm that and then try to undo whatever is reported to us,” said Mark Swartz, executive director of LCBH.

“From a legal aid perspective, it makes it very unlikely that we can assist people who had something in court that we believe should be reconsidered or potentially appealed.”

Tenant advocates said transcripts of eviction hearings are essential in reversing cases where the judge ruled improperly, where there was a due process violation, or when a judge did not ensure that tenants fully understood an agreement with a landlord, which can be grounds for reversal under Illinois court precedent.

Tenants and landlords can pay for their own court reporter, but this is often cost-prohibitive, and requires knowing ahead of time that a court reporter would be useful. Without recordings, the tenant or landlord can appeal with a “bystander’s report,” a written description of the hearing from someone who was present. Illinois courts have ruled that it is constitutional to not provide court transcripts in eviction courtrooms because bystander’s reports are an option.

But useful bystander’s reports are rare, lawyers said. Without legal training, litigants may find it difficult to remember details to put in a report, especially if they do not realize they need the report until weeks later. And unlike with an official transcript, opposing parties can dispute the information in a bystander’s report, creating a “he said, she said” situation.

Advocates Want Increased Accountability and Transparency

Having a recorded transcript of eviction court proceedings is also necessary to hold judges accountable, lawyers said. In a statement advocating for eviction court recording in 2016, Lawrence Wood, director of the housing practice group at LAF (formerly the Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago), compiled a list of several inappropriate comments that he and his staff have heard judges make in court, such as, “If I followed appellate court precedent because I’m paid to, I’d be no better than a prostitute,” and, to a subsidized housing resident, “If the conditions are so bad in your apartment, why don’t you just move?”

“If every judge knew there was a written record, I think it would be much more difficult for judges to color outside the lines,” said Charles Drennen, the CEO of legal firm Chicago Tenants Rights Law. “I also think it would be much easier for the Judicial Inquiry Board to make determinations as to whether judges have behaved within the bounds of their ethical obligations.” Drennen said that both landlords and tenants tend to think that eviction court judges give the other side too much leniency.

The Autonomous Tenants Union (ATU), a volunteer tenants collective organizing for housing justice, describes the lack of court reporting as part of a system that it sees as stacked against tenants. In an emailed statement to Injustice Watch, the group said, “Perhaps if there were court reporters, we could see the ways in which pro se tenants are not listened to on a mass scale . . . There have been cases in our experience in which landlords have been able to disobey agreed upon terms or judges have been unnecessarily harsh to tenants in court.” ATU seeks to ensure that tenants they work with have legal representation, or at the very least a companion who can observe the proceedings, as often as possible.

Cook County eviction courts have had court reporters in the past, but in 2003, they were cut due to a lack of state funding. After that, recording equipment was briefly used, but the recordings ended in 2004, according to Milhizer, Evans’s spokesperson. The state only funds court reporters when they are required to by a law or rule, Milhizer said, so those are the only court reporters consistently provided by the circuit court.

Some courtrooms, such as traffic court, currently have electronic recording equipment in lieu of court reporters. Even Cook County administrative law hearings are recorded, though only tickets for violations of county ordinances are on the line—a less severe repercussion than even having an eviction filing on one’s record, which legal aid groups say often causes landlords to refuse to rent to a person, regardless of the outcome of the case.

“I think that the decisions about where court reporters or recording devices get placed are based on what’s at stake,” said Ryann Moran, supervising attorney of the civil programs at Cabrini Green Legal Aid. “A lot of people, they think, ‘Well, if you didn’t pay your rent, of course you have to go.’ But maybe conditions were bad, maybe the person didn’t really do what they’re alleged to have done . . . For low-income people, it’s really high-stakes for them, but I think a lot of people don’t see it that way.”

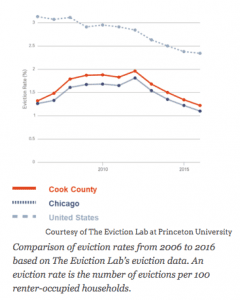

The Eviction Lab at Princeton University released the first nationwide dataset of evictions in the U.S. earlier this year. It reports more than 30,000 eviction filings and nearly 11,000 completed formal evictions in Cook County in 2016. That means there were an average of about 30 evictions a day in 2016, though the eviction rate in the county has been declining for several years. (The LCBH recorded a higher number of evictions than The Eviction Lab based on its own review of Circuit Court data, which included slightly different data and estimated sealed eviction cases, and reported over 15,000 evictions in 2016, or an average of about 42 evictions per day.)

The lack of eviction court reporting is just one facet of a larger problem of inadequate transparency in eviction courts; the available filings exclude vital information such as the reason for the eviction, said Philip DeVon, eviction prevention specialist at Metropolitan Tenants Organization. The March LCBH report found that 39 percent of completed eviction cases from 2014 to 2017 resulted in no eviction order or other judgment against the tenant, but those eviction filings typically remain on the tenant’s record, with no information about what ultimately happened in the case.

“It’s frustrating to be telling your tenants over and over you’ve got to document things to protect yourself,” DeVon said, “only to have them go to court where they’re supposed to find justice and the court doesn’t document things.”

Fowler carries a file of documents proving her case: printouts of emails between her and her property management documenting her concerns about lack of heat; receipts of money orders to show she paid her rent on time; records from city visits to inspect the apartment; copies of the motions she filed in eviction court. But none of it was enough to change the outcome. She must be out by the end of this month.

“It’s like your life stops and it all revolves around this issue,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Injustice Watch.

Comments