HOPE conducts outreach during a community event in Mississippi. Photo courtesy of Hope Enterprise Corporation, Hope Credit Union

At a recent Opportunity Finance Network conference, a colleague expressed concern about a “paradox” facing some urban areas in the country where community development financial institutions (CDFIs) have invested. The success of CDFIs in attracting investment has transformed these once-distressed neighborhoods into communities with flourishing housing stock, strong schools, health care facilities, and a thriving market. The paradox arises when community transformation pushes out the very people the CDFIs sought to assist because they can no longer afford to live in the neighborhoods they once called home.

While I agree with my colleague about the importance of ensuring that low-income residents and other vulnerable populations are not displaced by economic prosperity, this challenge is one I would heartily welcome in the region served by HOPE.

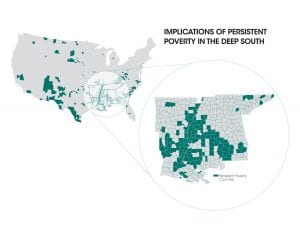

The Deep South is home to one-third of the nation’s persistently poor counties. For nearly a quarter of a century, we have been chipping away at the barriers people here face just to access the basics—a bank account, healthy food, quality schools, and affordable health care. We are adept at innovative financing, cobbling together and stretching any resources that trickle into the region, but capital has never come into this region at a level that brings communities anywhere close to gentrifying transformation.

Needless to say, we are not facing an influx of hipsters in the Mississippi Delta.

According to a report from the National Committee on Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) and Grantmakers for Southern Progress (GSP), grantmaking by the nation’s largest foundations averaged $41 per person in the Alabama Black Belt and the Mississippi Delta. That compared to the national average of $451. An even starker disparity is found when you compare the South to the state of New York, where the average is $995 a person.

Resource disparities in community development are not confined to the philanthropic sector. We also find that federal incentives for community reinvestment by banks have an uneven impact. And, once again, our geography works against us. The Community Reinvestment Act was ostensibly designed to strengthen distressed urban and rural communities. As such, banks get brownie points for investing in their CRA assessment areas, or the communities in which they are located. Of the 20 largest banks with operations in the Southeast, only one has at least one assessment area in the Mississippi Delta. This lack of an incentive means that banks are barely doing any development lending in one of the most impoverished regions of the U.S.

If foundations and other private sector grantmakers are reluctant to channel support into the Deep South over questions about the effectiveness of organizations and institutions located there, allow me to allay those concerns. A recent publication from the Urban Institute, “Expanding Community Development Financial Institutions: Growing Capacity Across the U.S.,” noted the effectiveness of CDFIs, but also found that the institutions were not serving all areas of the country where there is need. According to the report, 27 percent of the nation’s distressed counties had no CDFI activity at all.

Alabama is one of those places severely lacking in CDFI investment. More than half of the counties in Alabama had zero average CDFI loans per person, under 200 percent of the federal poverty level between 2011 and 2015. And like so many other communities in our region, the poverty in Alabama disproportionately impacts communities of color. Of 11 majority Black counties in the state, 10 (90.9 percent) have poverty rates that have exceeded 20 percent for more than three decades. In contrast, 12 of 45 (26.7 percent) majority white counties experience persistent poverty. HOPE recently expanded into Alabama by merging with Tri Rivers Federal Credit Union in Montgomery.

This clarion call to the banking industry, private sector investors, and other philanthropic organizations comes at a time when our nation is becoming increasingly more diverse, and those diverse populations are being forced to the economic fringe. For instance, nearly half of all Mississippi children live in poverty, and in 10 years, Mississippi’s population under 19 will primarily be people of color.

Failing to address these gaps comes with consequences. Take the recent report from Prosperity Now, “The Road to Zero Wealth,” which shows that if left unchecked, the ever-widening wealth gap will leave African Americans with zero wealth by 2053 and Latino households following suit by 2073.

If America is to reverse these trends, we must level the playing field. CDFIs have proven their worth and have shown an acumen for deploying resources in sophisticated transactions that transform declining neighborhoods and improve lives.

It is often said that you get what you pay for. Clearly, too little is being paid to create positive change in America’s most vulnerable places.

Comments