I recently had a revelation about the American approach to racial integration. We’ve been doing it all wrong, and it’s had disastrous effects on African Americans. Our cities are facing another integration challenge today, and we’re in danger of repeating the same mistakes.

Let me present a few provocative counter scenarios to show you what I mean.

What if, when the time came for baseball integration, the major leagues merged with the Negro Leagues? Instead of identifying a handful of early players who had the grit and toughness to deal with the ostracism, perhaps a handful of Negro League teams in the 1940s could have become full MLB teams, and the rest of the Negro League players put into a supplemental draft for all teams. Four Negro League teams from four markets untouched by MLB at the time—the Baltimore Elite Giants, the Newark Eagles, the Indianapolis Clowns, and the Kansas City Monarchs—could have become full-fledged MLB members, and more players would have had a shot at major league play.

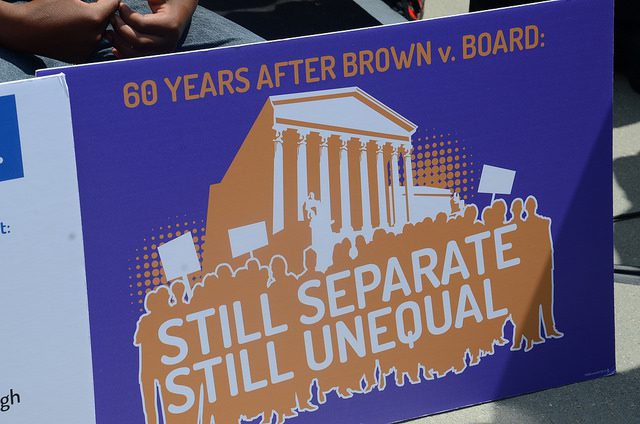

What if, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, segregated white schools were required to admit not only Black students, but Black faculty and administrators as well?

When segregated white schools finally addressed integration, they did so by dispersing Black students among several white schools, and generally shutting down the Black schools they came from. Black teachers and principals were often left completely out of the integration process, and black students lost a critical support group during a difficult period.

What if, instead of outlawing housing discrimination by race, religion, national origin, and all other protected classes, the federal government outlawed specific practices (exclusionary zoning, redlining, discriminatory public housing and urban renewal, discriminatory real estate practices like steering or contract buying, among others) and at the same time required all local jurisdictions to provide housing for all persons at all income levels? Mid-century American suburbs would likely have seen an increase in working-class and low-income housing, becoming far more diverse far earlier than it has. Cities would have seen an uptick in high-end construction far earlier as well. On the whole, there would have been greater balance in urban and suburban property values, then and now.

In reality, however, America did something quite different. Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey sought out the talent and personality of Jackie Robinson. The Little Rock NAACP was forced to find the Little Rock Nine to push Little Rock Central High School toward integration. Individual homebuyers or renters were sent into sometimes hostile neighborhoods in the name of integration.

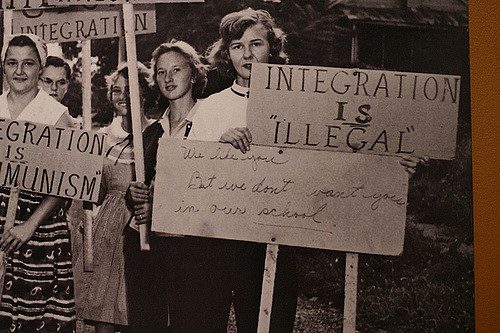

In reality, the burden of integration was always on black people.

Photo by techne via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

This hit me with full force after hearing a podcast by Malcolm Gladwell at Revisionist History. In his story about integration, titled Miss Buchanan’s Period of Adjustment, he talks about the aftermath of the Brown decision—how the Brown family’s intent was misread by so many, including the Supreme Court, and how it led to tragic unintended consequences. One of those consequences: the number of African-American teachers in the South, to this day, has never recovered from its heights during the Jim Crow Era because school systems, administrators, and school parents believed they could deal with Black students in the classroom, but could not abide being taught by Black teachers.

In each of the real scenarios, two systems were (or are) at work, and African Americans were seeking to operate on a level playing field. There were two baseball “systems”—MLB and the Negro Leagues. There were two school “systems”, explicitly so in the South but implicitly so in the North—one for whites and one for blacks. There are two housing “systems” in our metro areas, for blacks and whites.

Here’s the problem. When our nation’s power structure looks at these dual systems, the assumption is that one is superior and the other is inferior, and thus, barriers must be broken so that people can flow to the clearly superior system. In pursuing integration, our society destroyed one system in the name of inferiority, while never fully accommodating the needs of those dependent on another.

But really, were those “inferior” systems really inferior? There are many accounts of Negro League teams playing exhibitions against MLB teams and winning with regularity. What about the Brown family in the Brown v. Board case? They were quite pleased with the quality of education, the excellence of the faculty and staff, at the segregated school their daughter attended; they brought up the case because their daughter was forced to attend a school several miles away, when another school was available just four blocks away. But because of the assumption of inferiority, the power structure sought to be expansive rather than inclusive: meaning that it would expand one system in the hopes that it would accommodate more participants, rather than fully include the other system fully into the mix.

In fact, when it could, the power structure effectively destroyed one system in favor of the other. The Negro Leagues were effectively defunct by the mid-1950s. The expansion of suburban school districts at the time of rapid suburban expansion, accompanied by policies that kept blacks out of suburbs, led to resegregation and negative impacts in urban school districts.

Back to housing, where we have another conflict of systems. Urban revitalization has produced a lot of angst. There are newcomers with lots of anxiety about their imprint on formerly low-income communities. There are longtimers who are fearful about the change coming to a neighborhood they hold near and dear. Increasingly, the newcomer response has been to expand its options. Yes In My Back Yard (YIMBYs) say: build more housing and prices and rents become more affordable, and we can rid ourselves of the displacement angst. Longtimers, in voices that are seemingly heard less and less, call for an inclusive approach to revitalization; something that allows them to stay in place, and benefit from positive change as well.

History suggests it won’t go well for the longtimers.

A version of this post originally appeared on The Corner Side Yard.

I would like to remind readers that many of the housing practices mentioned by Mr. Saunders are indeed illegal, and have been for decades — as one example, redlining was outlawed in the 1970s. Sadly, though, where you have housing you will also find racist practices among realtors, mortgage brokers, and even community groups. Better enforcement is necessary, as is a stronger approach by community development orgs and other nonprofits. We have to commit to a zero-tolerance policy on discriminatory business practices, and work harder to ensure predatory landlords and speculators aren’t given a warm welcome by local governments.

If we truly are about changing the housing landscape, and creating inclusionary neighborhoods, we need to start with our own neighbors — putting the burden of undoing racism, as Mr. Saunders rightly said, should not be the weight for Black people to carry.

Exactly, Ms. Ott!

Excellent points all, Mr. Saunders. One of the more successful efforts to overcome the housing segregation forced upon us is Oak Park, Illinois. While integrating, Oak Park placed the weight on everybody, especially in its public schools where children of all races and incomes were bused to assure roughly similar racial composition in each school. That was an essential strategy to take the racial composition of the public schools out of the equation when households were looking for housing in Oak Park. Equally important have been the efforts of the Oak Park Regional Housing Center to expand housing choices beyond the usual ones of whites looking only in overwhelmingly white neighborhoods and African Americans looking only in integrated and predominantly Black neighborhoods — the long time recipe for maintaining segregation and resegregating communities.

And let us not forget that nearly every school integration effort was doomed to failure because that is what those boards of education wanted — they deliberately designed court-ordered integration to fail. No question about it.

The reality, though, that Mr. Saunders and just about everybody else has resolutely unrealistic expectations of the pace at which we can achieve racial and economic housing integration. The reality is that you cannot overcome the effects of 300 years of slavery and 100 years of Jim Crow and all levels of government forcing housing segregation on us (see Richard Rothstein’s tome, “The Color of Law: The Forgotten History of How Government Segregated America”) with just 50 years of half-hearted, difficult to enforce fair housing and civil rights laws. Societies with such in-depth bigotry do not change that rapidly. Given all the reasons people move where they do, it is very unrealistic to expect everybody (or a high percentage of households) to place making an integrative move ahead of all the other reasons like job location, schools, proximity to family, etc.

I’m not suggesting the slow pace of housing integration is desirable. But it is unavoidable, especially since governments continue to avoid even addressing the subject. I’ve conducted a good number of “Analyses of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice” and, frankly, the local officials who even want to address housing integration (the core issue of these mandated studies) are few and far between. We’ve actually been asked, “But don’t blacks just want to live together?” One of those who asked us that is now Assistant Secretary for Housing & Community Development at HUD.

There are strategies that work and they are detailed at https://www.planningcommunications.com/Ending%20American%20Apartheid.pdf

We’ve made some progress, albeit not enough. And now we’re living in a world where the White House is doing all it can reverse the progress we have made. But now is no time to back off. The stakes are too high.

There are too few programs and dollars devoted to renovation and rehabilitation of owner-occupied single family houses. Where this is enabled, people are given a realistic choice about what neighborhood they prefer, a choice that is not dictated by the physical deterioration of their homes. Many people prefer to stay in their long-time homes, despite being located in segregated neighborhoods. Repairing and restoring homes in poor neighborhoods preserves affordable housing, enables homeowners to remain in place, enjoying the fruits of housing price appreciation as the desirability of neighborhoods is gradually enhanced.

This is bullshit. Why don’t you just convince your people to stop? Because you are a part of it.

I’m amazed at how we keep focusing on trying to fix an institutional racist system and the laws or rule that aid discrimination, but we NEVER address the mindset that created the system and allowed segregation to develop in the 1st place. Did we really expect that people who despised us would just magically stop based on a few amendments, integration, or changing of a few laws that were controlled and enforced by the very people who are the oppressors? Did we think the bigotry, the stereotypes, the racism felt would just go away? Did we really want our students to be taught by teachers who wouldn’t even share a meal with them, our babies born surrounded by nurses or doctors who felt they were inferior. It seems to me that maybe we tried to integrate to soon and like the article said the burden is always on African Americans to adjust. We move in and they just move out. We could easily disperse low income families with vouchers in better environments rather than creating more project type low income neighborhoods where all low income families are still clustered together, but what happens, people decline vouchers still. Realtors still don’t show homes to certain people. Communities decline low income developments. Now don’t get me wrong I went to a majority white school & was bused from a all black area across the tracks but I had a strong black church as a foundation. Looking back we can’t change what happen but until we must learn. The oppressed can’t force the oppressor to see the error of his ways. It has to be other former oppressors or those that at least look like them that make the case or they just continue to get defensive.

I have to say I’ve lived in a majority white older neighborhood now for 20 years and always had one of the nicest yards. After getting laid off after 15 years, being a single mom, the stress of starting over, no health insurance, savings declined & difficulty finding new comparable job, things started to decline. I can feel myself being overly worried about what my new neighbors think and falling into the stereotype about blacks not maintaining their lawns because they don’t know my history. It may just be in my head, but still sad that’s its even a thought. For my generation being black came with daily pressure, the burden that we have to always dispel the myth or stereotypes placed on us as a whole.

Integration does not exist in a nation that never wanted at. Wake up❗️Doing the same thing over nd over is the true definition of insanity ❗️