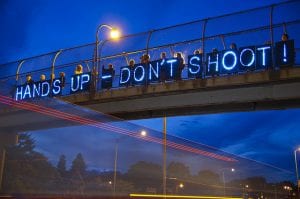

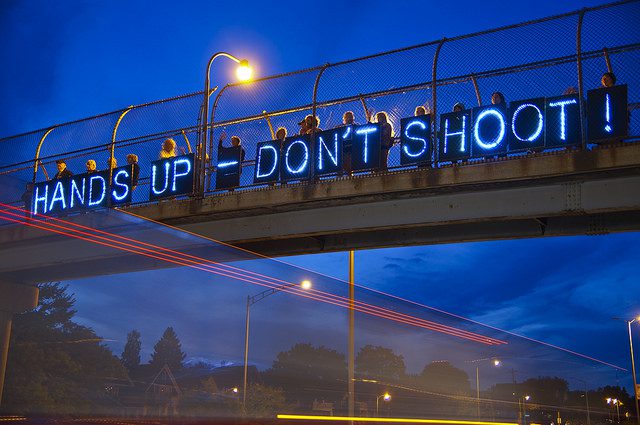

Joe Brusky via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0.

For the past 33 years in the country, the first Tuesday in August has been National Night Out (NNO)—public celebrations of police-community partnerships that are in part funded by the National Association of Town Watch.

For many communities, NNO is a fun summer night out, with free food, organized games, entertainment, and local law enforcement on hand to meet and interact with residents. For some other communities, NNO is possibly a public relations showcase for local police departments that at best have little community interaction the other 364 days of the year, and at worse, operate under strained or tense relationships with the people and communities they serve. My own towns’ NNO this year came at a time that leaned toward the latter.

Rewind to July 5, 2016, in Maplewood, New Jersey, when after our town’s annual Independence Day fireworks display, as groups of various size (and race) were dispersing, groups of allegedly raucous Black teenagers were in essence “herded” to the town’s border, the other side of which is Irvington, a predominantly Black city. On a very basic level, this was wrong, as many of the young people were residents of Maplewood and South Orange, and officers had no way of gleaning they were not residents beyond the color of their skin. But local outrage grew as stories emerged that some of the teenagers had been physically assaulted. Audio of the police radio communications from that night, as well as dashcam and other video was released last month—a year after the incident—and was damning.

Pressure culminated on August 8 when protesters gathered and spoke at Maplewood’s National Night Out, demanding accountability and action on the matter from the town council, which was meeting later that night. Residents marched to the council meeting—which happened to be held at police headquarters—and over 200 residents gathered to hear the council’s unanimous vote of No Confidence in the police chief, and order of his immediate suspension. At the expense of several young people’s dignity and sense of safety in their community, the incident has become the catalyst for calls of systemic change in how the town’s police departments operate to better reflect it’s stated values.

The towns are among the most racially diverse in the state, but they are not without the pain that often comes with that distinction.

Nationwide, incidents like this—and the ensuing delays in transparency and communication with the public—plague communities and breed mistrust. In communities of color, lower-income and not, relationships between police and residents have long eroded, and as such, many people who work in community development are conflicted.

While they often work with law enforcement to address concerns of crime and neighborhood safety, community development practitioners are also aware that many of the residents they serve have experiences of mistreatment at the hands of those same departments; and advocating for tougher policing or increased incarceration often creates the results that brought about the need for their work in the first place.

“I have worked with people in [lower income] neighborhoods that have reputations where they are under constant surveillance by policing, and their fear is [about] police response [rather] than criminal activity. The key here is what type of policing is going on in those neighborhoods and communities. Do you have community policing where the police officer is part of the neighborhood and community? Or do you have policing that is in the framework of storm troopers who come in and are guarding something outside of your community as opposed to honoring your community with service?”

These were the words of Stella Adams, chief of equity and inclusion with the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, who was part of a conversation on policing and community for our new Racial Justice issue. A group of several practitioners discussed how they navigate the conflict that is inherent in their work—from gang-related gun violence to implicit bias—and try to rebuild trust between police departments and communities.

Steve Lockwood of Frayser CDC in Memphis said that their precinct was recently given a community prosecutor, and while no one in a subsequent community meeting was clear on the specifics of that position, “… There was 100 percent unanimity that this is an over-incarcerated neighborhood, and that if this prosecutor’s job was to throw more young Black males in jail, we weren’t in,” said Lockwood. “But, on the other hand, if it was to [be] more sensitive to the community and to find diversionary stuff, particularly for new, young, nonviolent offenders, we were all in and we wanted to be partners. They’ve committed to that. We’ve simply said we’re going to hold [their] feet to the fire. We’re six or eight months into this, so it’s a pretty new experiment, but there’s a fair amount of evidence that shows that they are diverting young people who are new to the criminal justice system [and] putting them into other kinds of services, be it anger management or other kinds of counseling [or] GED services.”

Calls for restorative justice measures in place of incarceration, especially for young and/or nonviolent offenders, is gaining steam, and programs have been supported on both sides of the ideological aisle (for different reasons). A new film, “Tribal Justice,” explores two judges in tribal communities and how they use restorative justice in their communities to redirect the path that is often very fixed once new offenders enter the country’s traditional penal system.

For CDCs, the best solution of all may come from simply listening to your constituents, and letting them lead the conversation and the work. An example comes from the Center for Community Change Action Reinvestment team’s Counter-Conference for Safety & Liberation. The July counter-conference came during the National District Attorney’s Association conference in Minneapolis, and was staged to call attention to the “destructive impact of the larger criminal justice system’s on Black families an communities and the role District Attorneys play in perpetuating it.”

Police officers and their departments have the daily, face-to-face interactions that shape community perceptions and influence every encounter, and so it’s exceedingly important that their leadership acknowledges the history of their institution and Black America. It isn’t a good history. They should be honest about the reasons why it isn’t good. To join with communities and CDCs in acknowledging, then taking steps to heal that relationship seems the only plausible way to make both police and residents feel like they aren’t under threat. Here at Shelterforce, we’re encouraged by the programs and ideas we covered for this Racial Justice issue and are excited at the prospect of sparking more conversation. We invite you to participate.

Comments