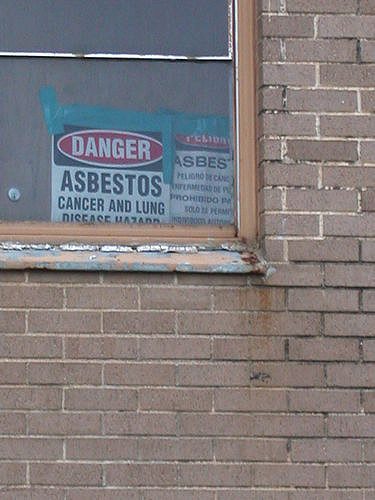

Photo by Marcia Cirillo via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Half a century ago, it wasn’t uncommon to see asbestos used in everything from tar paper for roofing, pipe insulation, caulking, ceiling tiles, and home insulation. Asbestos was durable, heat resistant, and cheap, making it a perfect home construction material. And though we have since learned how dangerous it is, approximately 700,000 public buildings in the United States may still contain asbestos—tucked away in insulation, acoustical plaster and concrete, fireproofing materials, floor tiles, and dozens of other applications. Frighteningly, this number serves as an indication of how prevalent it may be in private homes.

Today, federal rules prevent newly manufactured products from containing any more than 1 percent asbestos, and the Environmental Protection Agency is evaluating the substance to determine whether it needs to be banned entirely or regulated even more strictly. Considered safe when left alone, asbestos is incredibly dangerous when it is broken or damaged—creating dust that can be inhaled or ingested, often by people who don’t even know they being exposed.

Studies have shone a light on the prevalence of toxins present inside the homes of lower-income families. Chiefly among those toxins are radon and lead, and because lower-income housing tends to also be older, asbestos is another very real threat to the owners and inhabitants of those homes. The cost of lead and asbestos abatement totals in the thousands of dollars, and private homes aren’t usually included in asbestos regulation, so its removal becomes less of a priority for landlords, and is much less likely to happen at all.

For people living in substandard housing, the threats of lead and asbestos exposure are an everyday thing. Older housing that has been poorly maintained or where damage has occurred is more likely to contain these substances, compared to newer homes and houses that have been properly maintained and updated throughout the years. As a result, residents of poorer neighborhoods are more likely to deal with health issues stemming from polluted air both inside and outside the home.

Although there are abatement grants available through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Healthy Homes Initiative, they are only available to nonprofit and for-profit businesses, state and local governments, schools, universities, and federally recognized tribes. Private homeowners will undoubtedly have a more difficult time receiving grants for asbestos removal, but many states offer neighborhood revitalization loans to help spread out the costs of abatement over time, though the expenses are still incurred by landlords or homeowners.

In the case of Section 8 housing, asbestos is not listed specifically as one of 13 housing-quality standards (lead-based paint is included). Though it’s possible that a home could be rejected for Section 8 housing status because of exposed asbestos, it is not likely something an inspector will go out of their way to find. Because of this, a landlord or homeowner is more likely to invest resources into lead abatement, the presence of which can be visible in chipping and peeling paint on window sills or walls.

Asbestos fibers are microscopic—so tiny you can’t see, taste, or feel them when they are breathed in. But once they enter the body, the fibers eventually reach and adhere to the lining of organs, in most cases the lungs (though they can reach the abdomen or heart through the lymph nodes and cause tumors to form).

Developing an asbestos-related disease doesn’t happen right away. It can take 10 to 50 years before symptoms of asbestosis or mesothelioma begin to display, and by the time mesothelioma is discovered, patients are in the later stages when prognoses are very poor.

The United States has taken steps to limit the use of asbestos in homes, schools, offices, and even vehicles, but a full ban is still not in place. In 1976, Congress passed the Toxic Safety Control Act (TSCA), which allowed the Environmental Protection Agency to ban some uses of asbestos and regulate the material more effectively. However, the EPA had a chance to end the mineral’s use in 1989 when it issued a final rule through Section 6 of the TSCA. Unfortunately, the rule was vacated and remanded in 1991 by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. This is where it remained until last June when Congress passed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act.

The Lautenberg Act does for the EPA what spinach did for Popeye, boosting the agency’s regulatory power in taking action against dangerous materials. As part of the Lautenberg Act, the EPA was tasked with performing risk evaluations on 10 chemicals, including asbestos, to determine how dangerous they are to humans and what actions to take. The EPA is now in the midst of an evaluation that has to be completed within the next three years, and if asbestos is proven to be too high risk, an action plan needs to be in place within two years. However, with recent proposed cuts to the EPA’s budget, it may become more difficult for the agency to quickly complete the evaluation, which leaves others at risk of becoming sick.

With that said, even if the U.S. does opt to ban asbestos, it does not do anything for the many homeowners and existing building managers who will have to find a way to safely remove the material. There are options for schools and agencies through state and local means, and even loans and grants provided through the USDA for asbestos abatement for rural homes, but most homeowners will have to pay for removal on their own.

For those who believe there might be asbestos in their home or building, self-removal is highly discouraged, as the threat of exposure to loose asbestos fibers is a chance not worth taking. Only licensed asbestos abatement professionals can make the proper repairs (called encapsulation), or remove it safely.

It will still be some time until we find out if the United States will join Canada and dozens of other countries that have banned asbestos completely. Until then, education for small-scale landlords and homeowners on asbestos safety, and providing more help in accessing funds to remediate it from homes they rent is our best option.

I specifically am interested in whether or not that the apartments in HUD Housing have been cleared as “being free of Asbestos”? If not what are the risks for the Tenants?

The new home that I bought is of a lower-income area. It might be good to get it checked for asbestos. If I find any, I’ll be sure to have it removed.