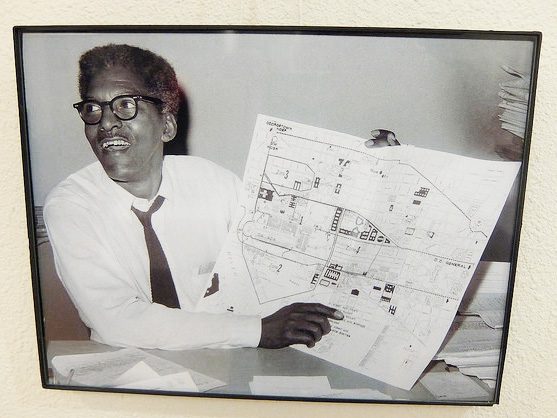

Photo by thekirbster, via flickr, CC BY 2.0

Last week, President Donald Trump announced his first budget proposal. If, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, a “budget is a moral document,” then this budget is a reflection of the moralities of the boardroom, the eviction notice, the emergency ward, and the pink slip. What it does not do is take a single step toward alleviating poverty or tackling the structural inequality which fueled the discontent that defined the 2016 elections.

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Trump’s budget will slash funding for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development by 13 percent, or $6.2 billion, compared to 2016 levels. When compared to funding levels needed for FY2017, the proposed cuts amount to a 15 percent, or $7.5 billion, reduction. This will result in an immediate threat to the homes of “more than 200,000 seniors and families, and people with disabilities will be at immediate risk of evictions and homelessness.” It also eliminates much of the resources that help low-income people access legal aid to fight evictions.

Trump’s budget reflects one more effort to abandon the democratic reforms of the New Deal and Civil Rights eras. Slashed, to various degrees, are the budgets for the departments of justice, labor, and education, as well as the Environmental Protection Agency. The only winners are homeland security and defense. This compounds the damage already made by previous administrations, both Republican and Democratic, who ran away from social progress in the post-NAFTA, pro-austerity years.

This budget is particularly striking when contrasted with others in the last 50 years, from the right or left. It has been compared to Ronald Reagan’s first budget in 1981, which began the shift of “national priorities” back toward extravagant defense spending (with average annual increases of 10 percent through the mid-1980s), lower taxes for wealthy Americans, and massive cuts in discretionary social spending, including Medicaid, food stamps, free and reduced lunch programs, transportation projects, education, and worker training programs. Democrats’ alternative budget that year claimed to do 75 percent of what Reagan’s did—including tax cuts and more defense spending—and failed miserably, as dozens of conservative and moderate Democrats voted for Reagan’s numbers instead. Economic growth followed, as did great inequality (exponentially so for the rest of the decade).

Fifteen years earlier, in 1966, King himself endorsed a budget, one that looked remarkably different than those proposed since.

The Freedom Budget for all Americans, authored by longtime civil rights activist and March on Washington organizer Bayard Rustin, was a “step-by-step plan for wiping out poverty in America during the next 10 years.” Rather than cutting spending (including defense) and changing tax rates (up or down), the budget proposed targeted investments simply through a “small portion of our future growth” to create more jobs. Such investments included the replacement of an estimated 9.3 million “seriously deficient” housing units and the building of thousands of hospitals, recreation facilities, and schools, all of which would create construction jobs, teaching jobs, healthcare jobs, and thus continue to grow the economy. In other words, Rustin and King endorsed a genuine infrastructure plan—if one views infrastructure as more than just roads and bridges, as important as they are.

As an example of how far our political imagination has retreated today, the Freedom Budget thought it would be possible to “have practically all Americans decently housed by 1975,” a vision that would automatically be relegated as utopian by contemporary standards.

Embraced by a broad coalition of civil rights liberals, the Freedom Budget represented a clear counterpoint at the time. Instead of accepting a conservative budgeting framework demanded by both conservative Democrats and Republicans, which routinely meant cutting domestic spending to pay for military expenditures or lower taxes, a progressive coalition promoted a confidence that poverty could be substantially reduced to single digits within a generation. The expansion of Social Security, the new federal healthcare initiatives Medicare and Medicaid, not to mention the various initiatives of the War on Poverty, had begun to do that already with only positive impact on economic growth. So why not invest in housing and education?

The optimism behind the Freedom Budget, however, proved fleeting. But not because it proposed too much domestic funding or raised taxes. Instead, white and Black progressives increasingly opposed the budget’s acceptance of current expenditures to fight the war in Vietnam. The Black Power movement also cast doubt on how much white liberals would really do for African Americans and other oppressed racial groups. The budget failed to be enacted as much from opposition among the left as it did from the right.

Our current challenges are a bit different from those in the 1960s. And yet history nonetheless offers important lessons. The Freedom Budget (and even Reagan’s first budget) remind us of a couple of important points. One, progressive forces should propose their own distinct budget to negotiate from rather than accept in any way a conservative blueprint that undermines the nation’s social contract. And two, progressives should stress how economic equity, and thus growth, depends upon a vibrant social infrastructure of quality housing, schools, and healthcare.

A new Freedom Budget should forgo nostalgia and embrace the priorities of today’s social movements such as the Fight For 15, The Movement For Black Lives, and the Undocumented and Unafraid. These movements insist on moving the demands of marginalized communities to the center of public discourse. Ideas around participatory budgeting could be incorporated to counter the tendency of liberal federal reforms to default to the top-down setting. Any new Freedom Budget must confront the need for a just transition away from earth-killing industries toward environmentalism rooted in equity. This would also call into the question Rustin’s strategy of funding such reforms only through growth. Yet putting forth an actual vision is an important step toward countering the conservative tilt in today’s populist upswing.

Fifty years ago, King asked Americans, “Where do we go from here?” The Freedom Budget offers one solid path forward.

The Progressive Caucus in Washington offers something very similar to what you describe, ‘A People’s Budget,’ and the most recent offering was in 2015 (for FY2016).

https://cpc-grijalva.house.gov/uploads/FINAL FY16 Peoples Budget.pdf

(ed. note: copy full address^^ from https to .pdf and paste into browser)

So it’s not that this should be done. It is being done. It’s more about how to ensure this alternative budget isn’t reduced to a press conference, largely ignored, and that it’s taken seriously by far more members in Congress.