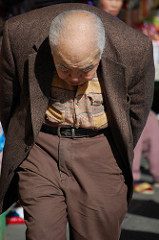

Photo by Ruby Gold, via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Video of Fox News personality Jesse Watters disrespecting Chinese people on the streets of New York’s Chinatown went viral last October. In the segment on the network’s “The O’Reilly Factor,” Watters mockingly interviews an elderly woman who apparently can’t understand him. As she stands there in silence, the piece cuts to a clip of Madeline Kahn from the movie “Young Frankenstein,” shrieking, “Speak! Speak! Why don’t you speak!”

The clip was viewed over 2 million times, and people voiced outrage over how Watters treated the elderly Chinese woman and generally mocked Chinatown residents. For me, the video highlighted how little mainstream Americans understand Asian Americans and its older population. It also sheds light on how our communities are often disparagingly treated like the older woman in the clip by both media and policymakers—who often assume that we remain placatingly silent to injustice.

Too many of us have the misconception that elderly Asian Americans live a charmed life that is financially secure with strong family ties. This isn’t accurate. The older adults featured in the Fox segment reminded me of the elderly clients that I served in Houston’s Chinatown. They too were limited-English-proficient, but also impoverished and seeking jobs to support themselves. For six years I worked as the director of senior and social services at the Chinese Community Center, which helps approximately 3,000 low-income seniors and families annually. These clients from diverse backgrounds live quite contrary to what mass media would lead people to believe about Asian Americans and wealth. They represent a part of the growing Asian-American population that is struggling to make ends meet, and growing even more acute for those over 65.

Older Asian Americans are more impoverished than their white counterparts at a rate of 13.1 to 9.1 percent. Between 2009 and 2014, poverty within the aging Asian American community increased at a rate of 40 percent, and 191 percent for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders. The Asian American Pacific Islander 65 and older population is expected to grow 352 percent to 7.3 million in 2060 and will comprise 21 percent of the total Asian American Pacific Islander population—one of the fastest-growing older populations in the U.S. With this staggering projected growth, now is the right time for Asian American Pacific Islander advocates to speak about the implications of poverty on our community.

Despite these dire statistics, some still argue that as a whole, Asian Americans are doing well. But that proof primarily focuses on younger Asian Americans with high education attainment and leaves out the struggling, older worker. It is true that Asian-American older adults are less likely to live alone and more likely to have support from family members—but those who are living alone are four times more likely than their counterparts to live below the poverty line. This reality is common for many, and forces older Asian American adults to work longer and get more jobs to cover basic living needs and expenses.

The jobs that are often available to older adults are limited, and low paying. Older Asian-American adults are contributing to the workforce in jobs where language capacity may not be an issue, such as the service industries and caregiving (I specifically remember one job-seeking client who spoke to me with hand signs and limited English, but needed a job so she could have money to eat). These jobs do not provide pensions or other opportunities to build savings. In Los Angeles County, for example, older Asian Americans are the least likely of all racial groups to have retirement income (16 percent), and they also have the lowest access to Social Security (66 percent), with the lowest median income at $9,736.

One possible policy opportunity that could benefit older Asian-American adults still contributing to the low-wage labor force could be expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit. Enacted in 1975, this tax credit for working families reduces the amount of taxes owed and may also provide a refund to low-wage workers between the ages of 25 to 64. In the 2014 tax year, 27.5 million taxpayers benefited from this policy. With bipartisan support, the tax credit has often been described as the single most effective antipoverty program for working-age households, but it could be strategically expanded to include childless workers who are under 25, and older workers 65 and over. President Obama’s administration had proposed an increase that would lower the eligibility age to 21 and cap it at age 67.

This could be a catalyst for progress, as exclusion of many low-wage workers has been solely due to age, but a recent report from the Social Security Administration confirmed that from 2000 to 2015, the overall labor force participation rate among individuals 65 to 69 rose from 30 percent to 37 percent for men and from 19 percent to 28 percent for women, so the age threshold for qualification should be re-evaluated. If given an opportunity to access the tax credit, older Asian Americans who are working part-time jobs at minimum wage may gain a foothold in lifting themselves out of poverty.

As an Asian American, I am glad that other communities of color are sparking and generating conversations around tough issues like the racial wealth gap. It’s time that our community join in on these conversations and present data and stories about our underrepresented, low-income Asian-American communities.

Our perceived silence should not allow others to think they can ridicule and exploit our communities. So, to respond to the question of, “Why don’t you speak?” we, as an Asian American and Pacific Islander community, need to gather like other communities of color to collectively speak up around issues affecting our community’s access to economic opportunities.

Comments