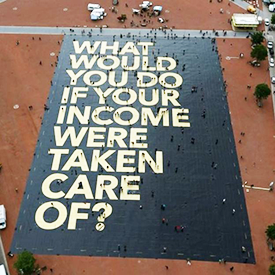

The Committee for the Initiative for an Unconditional Basic Income installed an 8,000 square meter poster on the Plainpalais Square in Geneva, Switzerland on May 14, 2016. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse

In 2005, an economist at the University of Manitoba uncovered boxes of archived papers that documented a program the Canadian province had undertaken three decades earlier. The program, called Mincome (short for “minimum income”), was designed by Manitoba to test the idea of providing adult citizens a stipend—regardless of employment status or age. It was an effort to discover whether just providing poor people with what they needed more of—money—instead of an array of other social support services, would discourage work.

Beginning in 1974, Mincome payments were distributed to more than a third of low-income residents in the small, farming-dependent city of Dauphin. The program lasted until 1979 when a more conservative Canadian government took office and pulled the plug on it. Though the program ran for years, a final report was never released.

The university economist and researcher who found the Mincome papers was a first-year economics student when the program began. She conducted her own research and found evidence that the outcomes of the five-year program were generally positive. Mincome recipients who were primary breadwinners did not stop working, according to the findings, but teenage sons, who customarily dropped out of high school to work and contribute to family earnings, stayed in school and graduated. Hospital visits also decreased substantially. An 87-year-old woman, who recounted her family’s experience receiving Mincome for The Huffington Post in 2014, said the program was “not really charity, it was need,” and it had helped the family achieve financial stability.

In Theory

The Mincome program likely served as inspiration for the president of a California tech investment firm called Y Combinator. In January 2016, Sam Altman wrote in a blog post on the firm’s website that basic income was something he’d been intrigued by and that Y Combinator would fund its own basic income study. He discussed technological advancement and how it will not only continue to make human life better, but will also eliminate traditional jobs. “. . . It’s impossible to truly have equality of opportunity without some version of guaranteed income. And I think that, combined with innovation driving down the cost of having a great life, by doing something like this we could eventually make real progress towards eliminating poverty,” wrote Altman. “Do people, without the fear of not being able to eat, accomplish far more and benefit society far more? And do recipients, on the whole, create more economic value than they receive?”

He is not alone in this assertion. In a recent interview in The Atlantic, Andy Stern, former Service Employees International Union president, spoke about the rapidly changing nature of labor in the country. Through discussions with corporate leaders, economists, researchers, educators, and local organizations, Stern said he’d come to the conclusion that the future of American work will be predominantly reliant on self-management. “. . . The growth in alternative work relationships—contingent, freelance, gig, whatever you want to call it—is clearly going to increase,” he said, adding that even conservative estimates for job disruption—via automation and artificial intelligence—are massive, and 20th-century concepts of wage and job growth will no longer exist.

Stern, a self-described “product of the one-job-in-a-lifetime career,” is now a proponent of basic income. He says the American ideal of upward mobility being tied to hard work may no longer be a reality. “I think some of this worship of a work-centric economy is very illusory for many Americans. We’re now seeing the limits of the traditional answers—if you just worked hard or just got a degree, things would be fine. Now we find people with advanced degrees, adjuncts, having a hard time getting by.”

Basic income, or universal basic income (UBI), by definition, is a regular and guaranteed payment from a government to all of its citizens. The payment, whether distributed monthly or annually, is an amount designed to support basic needs. Programs that focus on low-income earners and the poor have been called “guaranteed minimum income.” This support typically rises or falls based on a person’s earnings so that no individual or family falls below a minimum amount of income and into destitution.

The Y Combinator’s basic income pilot is a shorter-term (currently planned for one year, according to a firm spokesperson), smaller version of an original five-year long plan, and will reportedly follow 100 individuals and families from Oakland, California, and focus on methodology—how to deliver payments, select participants, collect data, and other details. The company chose Oakland because of the city’s wide cross-section of backgrounds, its “considerable inequality,” and its proximity to Y Combinator’s offices in Mountain View, which will enable the team in charge of the pilot to better manage it.

For participants, the payments will come with no strings attached. “People will be able to volunteer, work, not work, move to another country—anything. We hope basic income promotes freedom, and we want to see how people experience that freedom,” Altman wrote in his blog post. Y Combinator says it is working with community groups and Oakland city officials on the pilot, and if it goes well, the company plans to move on to the longer study.

In Practice

This won’t be the first time such an experiment has been undertaken in the U.S. In the 1960s there was serious debate among politicians, academics, and advocates for the poor about a guaranteed annual income (GAI), which had been born from the idea of “shared obligation” as well as the belief that citizens’ safety and health was the responsibility of government. In 1968 the government proceeded to conduct large-scale “negative income tax” (NIT) experiments with randomly assigned participants in different parts of the country, from New Jersey and Indiana, to assess the effect that an income guarantee would have on a recipients’ desire to work, their food consumption, and health, among other things. According to a report published in the Monthly Labor Review in 1981, the experiments’ guarantee amount and tax rate varied among subjects, but generally, a tax rate of .50 and a guarantee amount equal to the poverty line at the time (just over $6,000 annually for a family of four in 1977) was offered to NIT participants.

Also around the same time, in 1969, newly elected President Richard Nixon, along with Urban Affairs Counselor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, unveiled the Family Assistance Plan (FAP) for poor American families with children. Nixon made it clear that FAP was not a basic income plan, but what he called a “floor under incomes” negative-tax plan that supported families, but still encouraged work. The FAP would work on a downward sliding scale for families with income up to $3,920. In his plan, a family of four with no income would receive $1,600 annually, which is equal to about $10,000 today. The plan was presented as a potential alternative to the country’s increasingly expensive and complex roster of social services that many economic experts and politicians believed encouraged dependence on government handouts.

The plan was approved by the House in 1970, but it stalled in the Senate. Amid opposition from both sides—some liberal lawmakers felt the plan’s income floor of $1,600 was too low, and conservatives disliked that FAP had no work requirement—Nixon continued to campaign for its passage. It wasn’t until 1972, when, recognizing a losing battle, Nixon ultimately let the bill expire as he began his reelection campaign.

The NIT experiments, however, continued until 1982. By their end, over 8,700 households had participated. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and The Brookings Institution, much of the program’s results were never published in a broadly accessible way. All of the participating states reported modest decreases in work, but those decreases could not necessarily be attributed to the participants’ income. Some people took time off to look for better work. Overall, the largest decreases (between 10 and 20 percent) came among mothers of young children, who often replaced their work with education or delayed returning to work after an absence.

According to a discussion paper on the NIT experiments from the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network, all of the states collected different data, and several rural sites kept track of educational attainment and child health. NIT showed a positive effect on attendance rates and test scores at the elementary school level, as well as a reduction in the incidence of low-birth weight. In the Seattle-Denver experiments, which used the largest number of test subjects, the number of adults pursuing higher education increased.

Current conversations about universal basic income tend to involve the entire adult population receiving a check, which is the premise of Basic Income Action (BIA), an organization whose mission is to educate and organize the public to enact a guaranteed basic income for all Americans. Dan O’Sullivan, BIA’s founding committee member, believes the idea is gaining traction in part due to the internet’s penchant for making fringe ideas go viral, but also the public’s desire for large-scale change. “. . . [Universal basic income] is an idea that’s big, bold, and exciting. That’s the trend, politically, in recent years. If you look at the issue of gay marriage, the LGBT community didn’t settle for civil unions, they laid out marriage equality as the goal, their North Star. And we’re seeing the same thing in the Fight for $15—that bold demand attracts a lot of folks in our precarious economy today who are looking for answers. [Basic income] is the boldest idea: that every human being should have enough money to survive.”

BIA focuses on the idea’s core principles: universal (meaning for the entire population, regardless of income), basic (meaning able to be lived on), and guaranteed (something people can count on permanently). O’Sullivan believes that the freedom UBI can grant is what will ultimately win people over. “The ability to work less, go back to school, make different choices. The level of economic desperation that can be lessened with basic income opens up opportunity,” he says. “There are people whose lives won’t be changed much by it—they’ll just have more money and spend more. But [not] people working two and three jobs, people with unstable wages who are working and living in poverty.”

“We’re stuck in 20th-century mode where the only way to get money is through a job, but there are fewer and fewer jobs, [and even] fewer good jobs. It’s this epic competition . . . and that equation doesn’t work anymore,” says O’Sullivan.

It is often the “universal” nature of universal basic income that sparks questions of how such a plan—in which every adult receives a payment regardless of income—would be economically sustainable for the country. For libertarian supporters of UBI, the answer is simple: that payment would replace all other social services, including those for unemployment, housing, and healthcare. For them, the switch would not only remove the stigma associated with and the inefficiency of social service programs, but the largest benefit would be a reduction of the role of government in the lives of individual citizens.

Some economists, however, have argued that even with full replacement of social services with a basic income, the $3 trillion it would cost to give every adult American citizen about $10,000 per year is equal to the nation’s total tax revenue and more than half of the federal budget, and thus unrealistic. In an interview with The New York Times, Robert Greenstein, the president of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), said such an overhaul would actually increase wealth inequality because funds allocated for the neediest Americans would then be stretched across the income spectrum—giving money to people who do not need it and perpetuating economic inequality, without any social safety net.

An option that gets around this is a wage supplement that would prop up income and mitigate decades-long wage stagnation. Proponents argue that it is better to compensate people for work rather than simply being born, but others note this could be considered government subsidy of corporate negligence. It also doesn’t address the issue of lack of jobs. A large expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a bipartisan-supported tax program for lower-income earners, has been suggested as an alternative to basic income in this vein.

As a person familiar with our nation’s history of assistance to the poor, CBPP’s Greenstein remains skeptical that UBI would gain political support. “The history of the last 50 years or so strongly indicates that cash assistance for poor people fares badly politically over time, while in-kind benefits (e.g., food stamps, Medicaid, rental vouchers) fare much better,” he says. “For example, I think cashing out food stamps would be a big mistake that would significantly harm poor people, because the cash assistance that replaced food stamps would likely be cut sooner or later. I very much wish that weren’t the case, but the history on that is compelling . . . . This unfortunate political reality is one of the reasons Nixon’s admirable plan failed on Capitol Hill.”

O’Sullivan believes UBI is fiscally possible, but knows it would take a major shift in American economic ideology. “. . . [The annual cost] would be about 16 percent of GDP (gross domestic product). That’s a big change for the U.S., but if you look at the Scandinavian countries, France, [and] other European countries, [they] regularly spend that percentage of their GDP on social programs. It’s about making a conscious decision that it’s worth spending money on,” he says.

A program similar to basic income—payments to citizens unrelated to their work—has actually been happening in the U.S. since the 1980s. The Alaska Permanent Fund, a program O’Sullivan describes as “pretty amazing,” has existed since 1982 and gives all Alaskan residents a yearly dividend payment from a fund that receives a percentage of the state’s oil and mineral industry revenue. The payment amount has fluctuated since 1982, but the lowest payment this decade so far was $878 in 2012, and the highest, $2,072, in 2015. O’Sullivan notes that the program is one of the reasons why Alaska has the lowest income inequality in the nation.

Much smaller versions of this exist in some states, in which people receive a utility bill credit. The funds are collected from industrial polluters who must buy permits, and a share of the revenue from permit sales is returned to the public. But if programs like these were expanded nationally, O’Sullivan thinks the impact would be considerable. “If the oil industry, Wall Street, nuclear, telecom—were all kicking in some of their revenue, you can imagine what that could do on a national level.” Rather than the current cap-and-trade programs for polluters, a “tax and dividend” program would return corporate payments directly to the public. “It wouldn’t be enough right away to cover basic needs, but it would be a foot in the door [to UBI],” says O’Sullivan.

Looking Abroad for Data

With the idea of some form of basic income floating around in more and more circles, two recent examples may provide much-needed insight into what the future may hold.

In 2013, an independent group in Switzerland collected over 100,000 signatures in order to bring a basic income proposal to a nationwide vote, which took place in June 2016. An exact payment amount was not presented as part of the vote, but the group had suggested a monthly amount of about $2,500 (U.S.) for each adult and about $640 (U.S.) for each child. The Swiss government voiced its opposition to the proposal and suggested that voters do the same, citing the potential of mass job resignations and probable tax increases. The proposal failed by a large majority, but the group claimed victory in bringing a discussion about the country’s inequality and poverty to the forefront.

In January 2017, several Dutch cities will begin giving 250 citizens who are currently receiving government benefits a flat monthly sum of just over $1,000 (U.S.) for two years. They will be broken into several groups with varying stipend conditions—some will not be required to work (as the system requires now), some will receive additional funds at the end of the month if they perform volunteer services, others will receive those funds upfront, but must return them at month’s end if they do not perform volunteer work, and yet another group will continue to receive their existing benefits along with the guaranteed income.

The hoped-for outcome of the experiment is to learn more about human behavior under varying circumstances, as well as to see if the program has the potential to be an alternative to the current welfare system, which critics say is wasteful and ineffective at reducing poverty.

It remains to be seen if basic income is an idea whose time has come in the U.S. The Y Combinator pilot is being run by a company whose business is about picking the best ideas and assessing risk, and so that is promising. Also, we now have more tools at our disposal than the Mincome and FAP experiments did to track, compile, and analyze the data on such programs. We also have an engaged public that’s paying attention.

Comments