At a recent panel at the Center for Community Progress’ Reclaiming Vacant Properties conference in Baltimore, I asked the audience, “Who’s heard that scattered site development doesn’t work?” Most raised their hands. But once they learned about the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model, they were talking about how they could try the model back home. Why? Because our study showed that this scattered site model is a cost effective method to create affordable rental houses that makes twice the positive impact on the surrounding neighborhood as single site new construction.”

Two Approaches to Increasing the Supply of Affordable Rentals and Removing Blight:

- Scattered site model: Developer acquires blighted abandoned row houses and rents them to qualified tenants. Targeted tenants are at or below 60 percent of area median income as determined by HUD.

- Single site new construction: Developer builds or renovates a building with a single entrance and six or more apartment units, or builds multiple units on a single parcel of land.

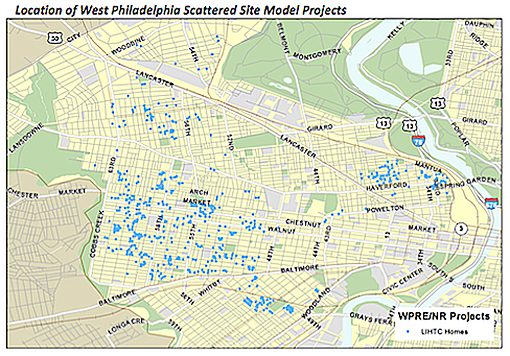

WPRE and Neighborhood Restoration, two private sector developers, created and implemented the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model from 1989 to the present in order to rehabilitate abandoned row house shells into affordable housing using Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) and private financing. The West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model has produced more than 1,100 units of affordable rental housing in 760 single-family houses or duplexes and has led to a direct investment of more than $160 million in West Philadelphia. The houses are located in some of West Philadelphia’s most economically distressed blocks. (See map below.) Summarized here are the findings of the study by May 8 Consulting and Reinvestment Fund that analyzes the impact of the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model rental housing built between 1989 and 2013 in the West Philadelphia area of the city. The results deepen our understanding of how to reactivate abandoned homes and revitalize the surrounding neighborhood.

- How Does the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model Work?

- What is the Revitalizing Impact of the Scattered Site Model in West Philadelphia?

- How Cost Effective is the Scattered Site Model Compared with Single Site New Construction?

How Does the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model Work? Developers WPRE and Neighborhood Restoration (WPRE/NR) created and implemented the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model in 1989 in order to rehabilitate abandoned row house shells into affordable housing. Since then, WPRE/NR have used the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model to rehabilitate more than 1,100 units of housing from abandoned, blighted single-family row houses and duplexes, and have maintained these units over the long term. Here are the four critical steps in converting abandoned shells to affordable rental housing:

Step 1: Buy Vacant Houses

Acquisition of vacant houses is the critical first step. For the most part, these are row house shells that have been abandoned for more than 10 years. Early on, WPRE/NR focused on acquiring properties on stable blocks that contained just a few vacant properties. When properties on these blocks were mostly redeveloped, WPRE/NR tackled blocks with multiple vacancies, ensuring acquisition of a sufficient number of these properties to stabilize the block. Over the years, WPRE/NR purchased these abandoned homes for a range of prices including $1 for city-owned properties, below market value bids at tax sales, and market value for privately owned listed properties. The average cost paid for the scattered site vacant housing units from 1989 to 2015 was $13,380, adjusted for inflation to 2015 dollars. Under the West Philadelphia Scattered Site Model, abandoned homes are purchased with an acquisition line of credit. The acquisition line is paid off once the developer breaks ground on the project and obtains a construction loan.

Step 2: Apply for and Receive LIHTC

WPRE/NR has applied for and received LIHTC support for 24 scattered site projects since 1989. The smallest project, in 1991, helped to fund the redevelopment of 10 units-six single-family homes and two duplexes. Two of the largest projects, in 2004 and 2006, funded the redevelopment of approximately 80 single-family homes each. In order to create a viable LIHTC project, an investor, typically a company, is identified that wishes to take advantage of tax credits. Prior to submitting a LIHTC application, WPRE/NR purchases a certain number of properties and obtains private construction and permanent financing to leverage the money allocated from LIHTC to redevelop as many new affordable rental units as possible. With site control of multiple abandoned properties clustered in the same area and with private financing, WPRE/NR next applies for LIHTC financing. If WPRE/NR’s project is selected by the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency to receive tax credits, the investor partner who receives the tax credits typically pays the present-value of the LIHTC credits over a period of time. These funds are then used by WPRE/NR for construction and development of the scattered site units.

Step 3: Rehabilitate the Houses

WPRE/NR performs gut rehabilitation on the abandoned shells that they acquire, completing about 60 homes per year or five homes per month. They strip the houses to their bare bones and build them new on the same footprint and with the same square footage. Often, the only original features that remain are the exterior walls. In each home, WPRE/NR provides all new plumbing, wiring, roof, floors, studs, and walls. WPRE/NR hires a general contractor to perform the rehabilitation work. The general contractor must provide documentation that they have at least 50 percent minority employees and at least 50% local resident employees. Since 2008, WPRE/NR has used sustainable building practices to ensure each home receives LEED certification by the U.S. Green Building Council, and Energy Star certification by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This ensures that all houses are energy efficient and utility costs are reduced to increase the home’s affordability. It also contributes to making each home warm, safe, and dry and lowers indoor air pollutants. Since 2004 WPRE/NR has provided each tenant with the ability to obtain free supportive services from the Public Health Management Corporation including:

- Preventive health programs.

- Job training and placement programs,

- Child care assistance services

- Substance abuse treatment

- Legal services

- And mortgage counseling.

Since 2004, 10 percent of homes rehabilitated have been made accessible for persons with disabilities.

Step 4: Lease and Maintain Homes

To qualify to rent a house, tenant households must have incomes at or below 60 percent of area median income. Most WPRE/NR properties offer three bedrooms, a basement, and a small yard. In the first 10 years, almost 90 percent of tenants had Section 8/Housing Choice vouchers. In 2015, only 40 percent of tenants used a Section 8 voucher, and the other 60 percent were able to pay the affordable market rents without assistance. WPRE/NR has created a property management program designed to provide quality, affordable scattered site housing to responsible tenants. Tenants sign a 1-or 2-year lease but tend to stay 3.5 to 4 years. An affiliate of WPRE/NR, Prime Property Management, leases and manages the units. Since 2000, the average maintenance cost per unit has been $1,200 per year. Operating expenses average $3,380 per year for each unit and include debt service, insurance, legal and professional fees, advertising, and taxes. Prime Property Management is responsible for fixing all systems within the house and the home’s structure. Prime Property Management has a full time staff of 16 employees. Half of these employees perform maintenance on houses, while the other half provide administrative support. Almost 90 percent of Prime Property Management employees are minority and live in Philadelphia, with about 70 percent living in West Philadelphia. The most common maintenance requests from tenants are plumbing issues and help getting into their locked unit when a tenant loses a key.

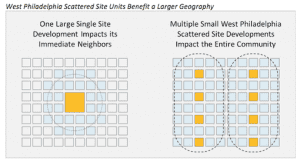

What is the Revitalizing Impact of the Scattered Site Model in West Philadelphia? The West Philadelphia Scattered Site housing model had a significant revitalizing impact on its surrounding neighborhoods. In fact, the study found that the scattered site rehabilitation model had twice the positive impact on the surrounding neighborhood as single site new construction. Property values are a good measure of overall neighborhood impacts because they show the willingness of homeowners or investors to pay for neighborhood attributes.

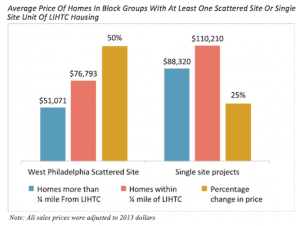

Home sales prices for houses within a quarter mile of West Philadelphia Scattered Site properties rose by 50 percent, while single site new construction increased sales prices by only 25 percent. Homes sold within a quarter mile of a scattered site property sold for an average of 50 percent more than those homes not located near a scattered site property. Homes sold within a quarter mile of a West Philadelphia Scattered Site house (roughly two and a half blocks) sold for an average of $76,793. Homes in the same census block group, but not located near a scattered site house – or sold before the scattered site house was rehabilitated – sold for only $51,071. The prices paid for homes located near scattered site projects were 50 percent higher than prices paid for homes not located near scattered site projects. The additional $25,722 real home buyers paid for homes near scattered site properties in West Philadelphia suggests they are having a positive effect on their surrounding communities. Houses near single site development show a smaller positive benefit of 25 percent on sales prices. Homes sold near a single site project sold for an average of $110,210. Homes in the same census block group but located more than a quarter mile away from a single site project, or sold before the single site project was built, sold for only $88,320. Single site projects were generally located in block groups with more expensive homes than scattered site projects. The development of a single site multifamily building resulted in an increase in price of 25 percent when compared with the prices paid for homes not located near single site properties. The following chart shows that the benefit of being located near a scattered site property is nearly twice as large as the benefit of being located near a single site project. The gold bar shows the percentage change in actual sales price and documents the fact that homebuyers were willing to pay proportionally more to live near the rehabilitated single-family homes that make up the scattered site development. Homes sold near a single site development, although more expensive to begin with, sold for only 25 percent more than homes not located near a single site development.

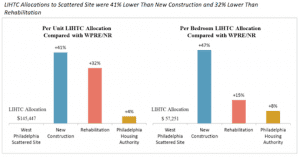

How Cost Effective is the Scattered Site Model Compared with Single Site New Construction? The West Philadelphia Scattered Site model created affordable housing for about 24 percent less cost than comparable new construction units in multi-family buildings.

West Philadelphia Scattered Site units cost 24 percent less than single site new construction and 27 percent less than other rehabilitation. Reinvestment Fund compared the relative cost effectiveness of the West Philadelphia Scattered Site model with other Philadelphia LIHTC developments constructed between 2005 and 2007. The analysis found that the scattered site rehabilitation model was more cost effective, even though the rehabilitation process is less predictable and more challenging due to housing stock that varies in age, condition, and construction methods.

West Philadelphia Scattered Site cost per bedroom was 32 percent lower than single site new construction developments and 10 percent lower than single site rehabilitation developments. Per bedroom, West Philadelphia Scattered Site development costs were 32 percent lower than new construction development and 31 percent lower than PHA projects. West Philadelphia Scattered Site developments were 10 percent less expensive per bedroom than other rehabilitation projects. Between 2005 and 2007, 68 percent of the units built in West Philadelphia Scattered Site developments offered three or more bedrooms, compared with 51 percent of new construction units, and only 48 percent of PHA units. Seventy-five percent of rehabilitation units offered three or more bedrooms.

West Philadelphia Scattered Site units used 41 percent lower tax credit allocations than new construction and 32 percent lower than rehabilitation. Scattered site rehabilitation required 41 percent less tax credit financing per unit than new construction projects and 32 percent less per unit than other rehabilitation projects. Per bedroom, West Philadelphia Scattered Site used 47 percent lower tax credit allocations than new construction projects, 15 percent lower than rehabilitation projects, and 8 percent lower than Philadelphia Housing Authority projects.

Conclusion: This study strongly suggests that it is time to take another look at scattered site rehabilitation as a cost-effective model for reactivating vacant properties and creating needed affordable housing.

Hello Karen – this my first real visit to this site…. great write-up and commend your evidentiary content and detail. How would MIHTC play out under this (or any current) scenario?