High-density public housing may seem like an idea whose time has come and gone, buried along with the ruins of notorious projects like St. Louis’ Pruitt-Igoe and Chicago’s Cabrini-Green. Since the 1990s, HUD’s Hope VI program has demolished hundreds of public housing projects, usually replacing them with lower-density developments that house far fewer people. But is the issue really about density? A remarkable project currently underway in Toronto suggests that sometimes higher, rather than lower, density may be the best way to go.

By the 1990s, Regent Park, a public housing project built in Toronto in the late 1940s, was showing many of the same problems that had prompted the Hope VI program in the United States. With over 2,000 housing units on 69 acres, located less than a mile from booming downtown Toronto, Regent Park had become Canada’s own poster child for distressed public housing.

Although the appetite for large-scale revitalization seems to be modest in the United States these days, looking at how Toronto is rebuilding Regent Park offers some intriguing lessons for the federal government, as well as for states and cities that are grappling with the challenges of remaking distressed public housing projects.

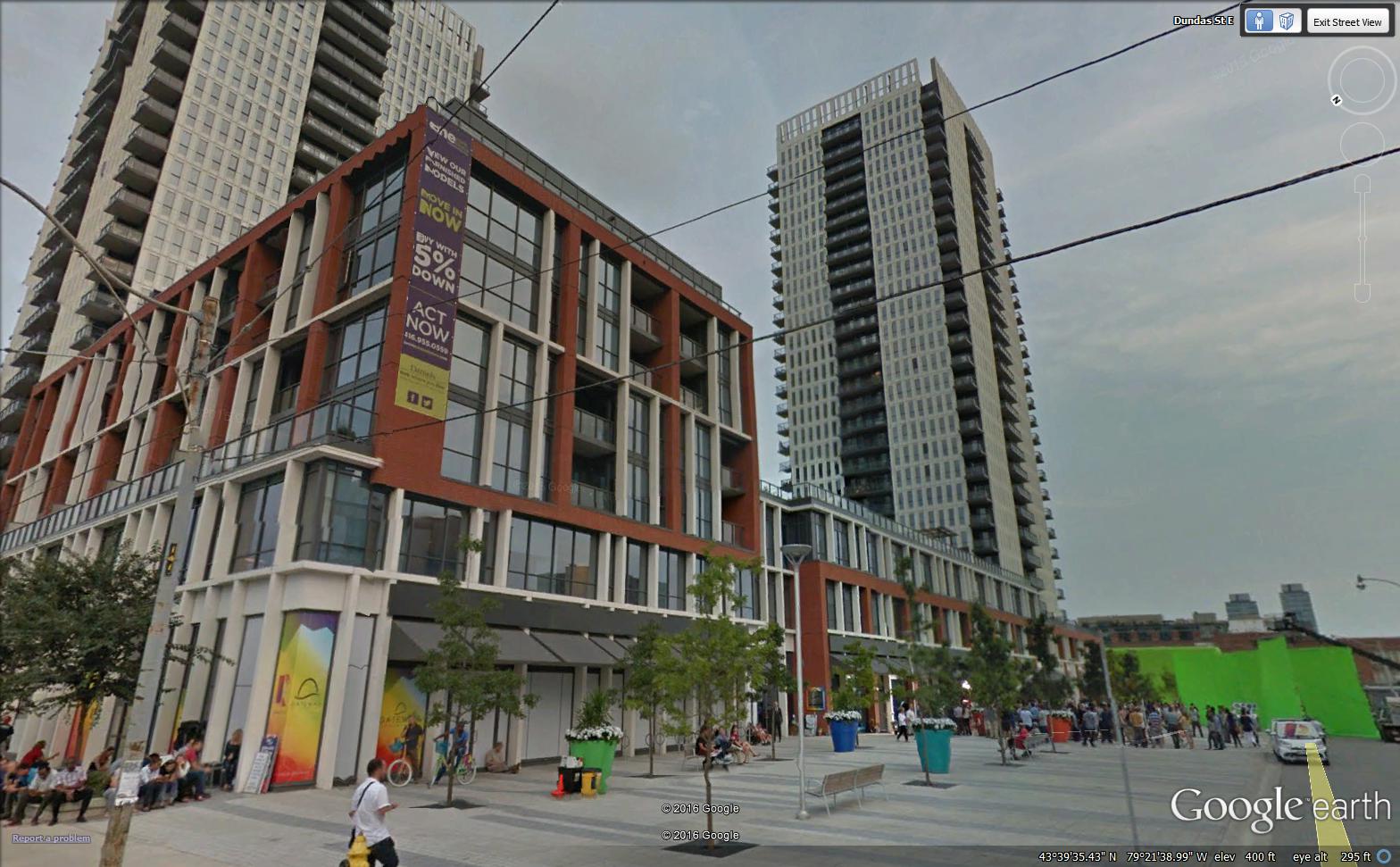

Don’t be afraid of density. When it’s completed, the new Regent Park will contain over 7,500 housing units—more than 100 units per acre. The site also includes extensive commercial space, public open space and community facilities. The increase in density means that the new community is walkable and compact, and that it can support major stores like supermarkets, along with restaurants and smaller stores, as well as actively use the recreational space provided. It also means that a source of internal subsidy is created—Toronto’s hot housing market helps–to underwrite much of the cost of the affordable housing. Most Hope VI projects, by contrast, keep the same or lower density; many end up with semi-suburban landscapes that, for all their New Urbanist rhetoric, are neither particularly walkable nor urban.

Replace the low-income units. All of them. When it’s completed, the new Regent Park will contain more affordable housing units–with rent geared to income, as the Canadians say–than were there before. Not only are all of the former public housing tenants given the right to return to the development, but lower income earning families are given an opportunity to become homeowners in Regent Park through a program that covers 35 percent of the purchase price, as long as they can afford to carry a mortgage on the remaining 65 percent. By comparison, most Hope VI projects replace only a limited number of low income units; most former tenants receive Section 8 vouchers so they can move elsewhere.

Create high quality amenities. Regent Park offers some of the best recreational amenities available in Toronto. The development includes a six acre park; nearly three acres of athletic grounds with a hockey rink, basketball court, soccer/cricket pitch and a running track; the Daniels Spectrum, an arts and cultural center with event, performance and exhibition spaces; and the Regent Park Aquatic Center, a multi-purpose swimming pool complex in an architecturally spectacular facility that the project architects describe as capturing “a feeling of transparency and connection to the outdoors.”

Be responsive to the community. Toronto is one of the world’s most ethnically and culturally diverse communities, and Regent Park is a microcosm of that diversity. According to one source, 57 different languages are spoken in the neighborhood. The planners of the new Regent Park have engaged the community in the planning from day one, and made a real effort to be responsive to this diverse community, particularly in meeting the cultural and religious needs of the area’s large Muslim community. The sensitivity of the planners to the needs of immigrant communities reflects a strong Canadian ethos, which is currently being seen in the country’s welcome for Syrian refugees. Canada, with 10 percent of the population of the US, has already admitted over 25,000 Syrian refugees, a number that is likely to double over the course of 2016. The Regent Park project includes a variety of educational youth programs and activities, as well as a large number of job-generating businesses, projected to create 1,100 new jobs, with neighborhood residents given priority for the jobs being created. Few Hope VI projects contain much if anything in the way of job-generating facilities, although to be fair, few are even close to the scale of Regent Park.

The program has not been without its problems, particularly with respect to relocation. With most of the city’s public housing stock located in outlying parts of the city, many residents have been forced to move–even if temporarily–to unfamiliar areas where they may feel isolated and uncomfortable. It’s not clear how many of the displaced tenants will in the end move back to Regent Park after being relocated. Still, even though it is still a long way from completion, it is an amazing achievement; and perhaps most important is the prediction of University of Toronto professor David Hulchanski, dean of Canadian housing scholars: “as time passes, people won’t know where Regent Park begins and ends.”

Readers interested in learning more about urban policy (and more) in Canada, and how the US can learn from the Canadian experience can look up Alan’s new book with Canadian planner Ray Tomalty, America’s Urban Future: Lessons from North of the Border, published by Island Press.

(Photo credits: 1-New development in Regent Park, Toronto, author image via Google Earth; 2-Old Regent Park Housing Development, author image via Google Earth; 3-Regent Park Aquatic Center by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects, photo by Shai Gil)

Alan–Can you give us any examples of the kinds of design or other decisions that resulted from “in meeting the cultural and religious needs of the area’s large Muslim community”? Curious what that looked like.