These statistics are well enough known, but we don’t think about them as much as we should, and often lose track of the actual human toll behind them.

A book coming out in March called, simply, Evicted, by Harvard scholar Matthew Desmond, tells that story. It should be required reading for anyone in community development (A paper by Desmond titled “Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty” addresses some of the same issues as his forthcoming book).

It’s a twofold problem: The most fundamental problem is that the economics of what poor people live on–either from public assistance or low-wage jobs–are totally inadequate to afford what it costs to create or provide even minimally decent housing. The 25th percentile rent in the United States–the low-end median rent, where 1/4 of the units rent for less and 3/4 rent for more, was $670/month, which takes an income of $26,800 to afford. Realistically, even the most self-sacrificing landlord can’t pay off a mortgage, pay taxes and maintain a rental unit in decent shape for what a poor family can consistently afford to pay.

The second problem is, of course, that our political system has failed to address this issue in a meaningful way. Instead, we have a sort of lottery, where a lucky few get housing vouchers, and the rest, for the most part, are out in the cold. What happens then? Poor tenants, whose incomes are not only low but highly unpredictable from one month to the next, live almost like refugees in a revolving door existence of substandard housing, dangerous neighborhoods, rent arrears, doubling up, eviction, and forced moves almost on a yearly basis.

Millions of people are evicted each year, and millions more move involuntarily without waiting for a formal eviction proceeding. Without a stable place to call home, these families live in a constant state of social and economic instability, their children moving from school to school, all perpetuating the multigenerational poverty that characterizes so many of our inner city neighborhoods, not to mention frustrating efforts by CDCs and others to build strong, cohesive neighborhood organizations and stable neighborhoods.

The response from the community development field, for the most part, tends to be to try to build tax credit housing. Yet, a recent HUD study has raised some tough questions about what tax credit housing means in this context. Even though tax credit rents are set at what a tenant at 50 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) can afford, the majority of tenants tend to have much lower incomes–45 percent have incomes below 30 percent of AMI, and another 19 percent between 30 and 40. But, unlike public housing, LIHTC rents are not adjusted to family incomes. This means two things: First, large numbers of LIHTC tenants make ends meet by getting a Section 8 Voucher, and using it to make living there affordable.

Although the HUD data is sometimes hard to interpret, it looks like at least 36 percent of all LIHTC tenants have a voucher or some other form of rental assistance. An educated guess is that at least 1 out of every 3 vouchers in circulation is being used in a tax credit project. Second, of LIHTC tenants who do not have a voucher, more than 60 percent are paying over 30 percent of their gross income in rent; in other words, suffering from precisely the cost burden that affordable housing is supposed to prevent. This probably represents a better option for most than private market housing–the quality of housing is likely to be higher, and in high-cost areas, like New Jersey or California, their cost burden, although high, may still be less than it would be on the private market. The point, though, is that LIHTC housing is, in the final analysis, not a solution. What is to be done, then?

If there is one issue that should be the focus of national advocacy efforts, it should be this one. The National Low Income Housing Coalition has done great work, but it is not enough. Rather than simply advocate for more vouchers, we should see this as an opportunity to take a close look at what the best way would be to fill the gap between what poor tenants can afford and what it costs for the private market to provide decent housing–and then try to build a broad coalition around it.

What would be the best way to meet these needs? I don’t know the answer, but it’s critical to ask the question. Over 40 years ago, then-President Nixon proposed a guaranteed annual income for every American family. Would simply putting more money into people’s pockets be a better way of helping them find decent housing, with fewer market distortions than the Section 8 program? Taking the opposite tack, could vouchers become more property– not project–based, with a competitive model where landlords of all stripes could compete for vouchers on the basis of price and quality? I’m sure there are other models worth looking at as well.

In the meantime, difficult as it may be, this is a critical issue for any CDC or other organization trying to build stronger neighborhoods. Tenants in private market housing, most of them low or very low income, make up half or more of the residents of most lower urban neighborhoods. We need to look at how the community development field can help better support tenants in private market housing. We have a fairly decent although patchy network of organizations in this country to help homeowners keep their homes, but nothing that I’m aware of to help renters keep their homes. Changing that is long overdue.

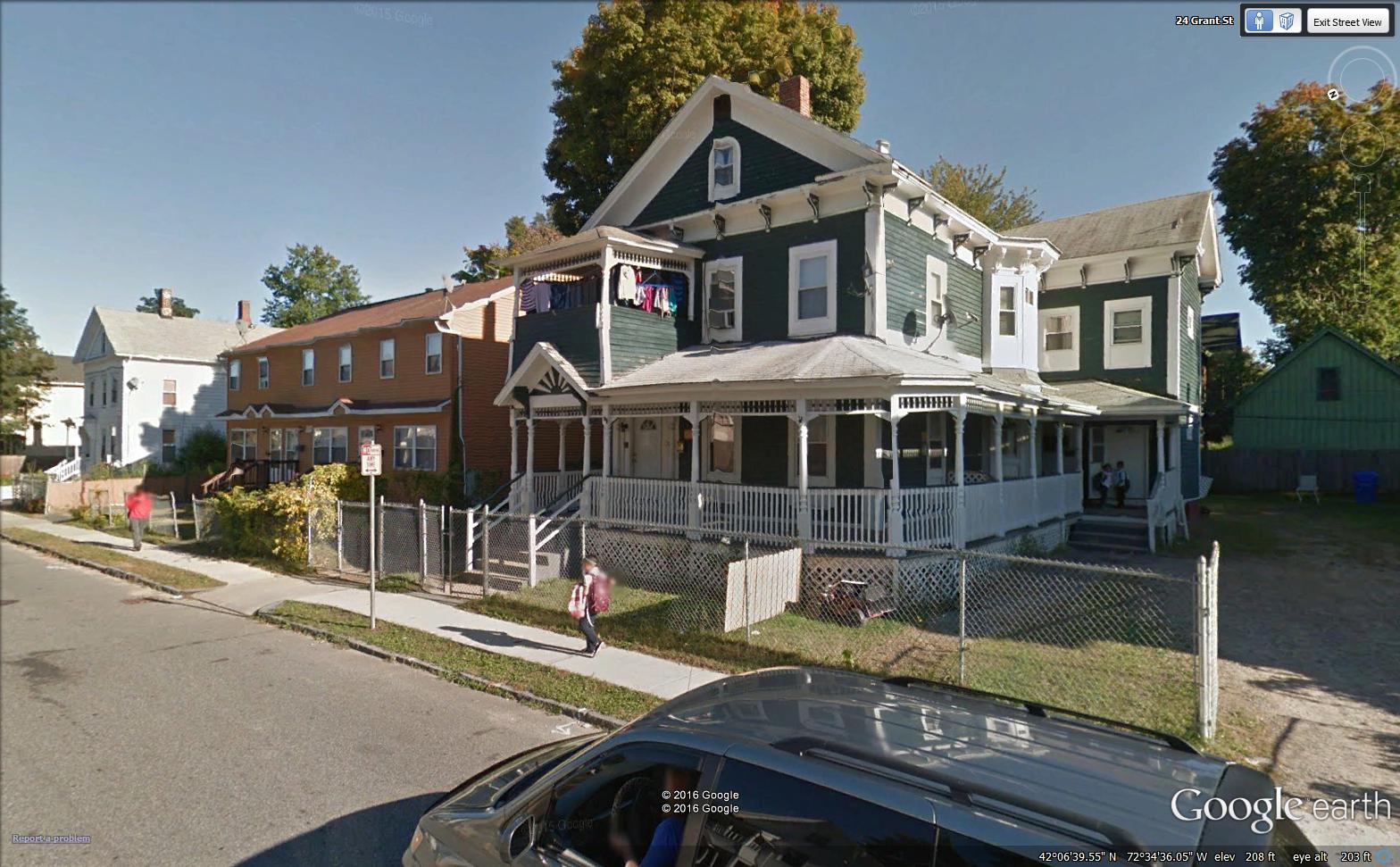

Photo: Small multifamily buildings in Springfield, Ma., courtesy of Google Earth, Alan Mallach.

As usual, Allan Mallach is on the mark. Thank you for making the point that we face a real crisis in housing instability among poor renters.

As Allan points out, tenants are often overlooked by many neighborhood groups and even CDCs, and disfavored by society. Counseling for renters and voucher holders is an eligible use of HUD housing counseling funds, but these dollars are spread thinly and grantees are almost entirely focused on homeownership.

Housing instability is such an important issue because it produces a range of problems for the children of poor renters —- jeopardizing healthy child brain development and lifelong health, as well as disrupting learning and socialization in school.

The bundle of services that we call mobility counseling is generally comprised of precisely the kinds of services that are needed by all renters to obtain and maintain stable housing: housing search assistance, follow up support, financial literacy, landlord/tenant intervention,, second move counseling, etc. But HUD generally hasn’t funded these services (the proposed budget includes funding for mobility counseling, but just $15 million nationwide, barely enough for 10 sites).

To be sure, funding to make housing more affordable is crucial, whatever the tools used to achieve that. But we also need to make these kinds of services available to poor renters on a widespread basis, starting with those most harmed by housing instability —- children and their families. Whether that funding comes through HUD, HHS, DoEd or as an interagency effort, it is long overdue.

Moderate income renters are facing the same housing instability as low income renters, yet they’re rarely asked to be part of the discussion, despite paying more than their fair share of tax dollars.

We need to reallocate incentives for building affordable rental housing in order to prevent middle-income families from sliding into poverty — something I’ve been advocating for years. Preventing people from becoming poor is far more cost-effective than having to constantly put out fires and “save” people once they’ve fallen off the cliff.

Until we start treating our moderate income renters with the same sense of urgency, we can watch our cities and counties go further into debt as their tax bases move away or sink into poverty.

A large part of this has to be a look at municipalities. Every municipality wants to raise property values to bring in more tax revenue. So they are resistant to low-cost housing; small homes, small lots, etc. They pass ordinances requiring facade improvements, landscaping, etc. They are resistant to multi-family housing.

All that drives housing costs. Until we find a way to make it easier for developers, especially private developers, to create affordable housing without subsidies, we’ll never solve this. Housing assistance should be concentrated on ELI and VLI families, but too much of it goes to households that shouldn’t need subsidies if the market was truly functioning.

Brian, I agree. However, I’m not sure what the solution is when large well-funded foundations don’t understand the need for moderate income housing funding, and banks are only funding homeownership projects — there needs to be a funding source for moderate-income rentals that isn’t tied to ELI and VLI families.

These comments are absolutely right on. The tax credit program does not support people who need housing the most. An income structure in addition to a development program with deep subsidies is the answer. Combine a below market interest rate loan program with home funding as rental subsidies

Excellent post by Allan Mallach on housing instability and the role of evictions. Where I differ is that work on eviction prevention should have no income limit and this includes greater advocacy to assist families and individuals in public housing and with other housing assistance to remain in their home. I will give credit to the Newport Housing Authority for asking the question- why are we seeing an increase in evictions?- then moving on to explore financial counseling and identifying other causes. Tenants far too often as the recent report looking at evictions in Baltimore attest lack legal representation and either have legal defense not raised or get pressured by the landlord’s lawyer to accept an eviction. I would welcome foundation funding to have tenant legal advocates in our courts to see this results in cutting evictions, regardless of income. Housing stability must be equated with eviction prevention efforts including sources of funding (grants and very low cost loans) to keep folks in their homes. The focus should not be on ones’ income or the type of housing assistance (if any) to averting evictions through legal advocacy, organizing and counseling.

Ray, the study, unfortunately missed a few points that are important to the outcomes of tenants in rent court.

In Baltimore, we do have a mediation process available to tenants, along with an organization (Baltimore Neighborhoods, Inc.) that operates a landlord-tenant hotline where tenants who do not meet BNI’s issue requirements (Fair Housing) are referred to other organizations around the city for further assistance. We also have legal orgs here that will take on landlord-tenant cases in court.

I think part of the bigger issue is a lack of capacity on the part of the orgs, and a lack of true outreach and marketing by these same orgs to get their names and services to the people who need them the most. I’ve often said that many of my colleagues need to get out of their offices and into the communities they claim to serve — otherwise, it feels very “ivory-towerish”. I have to say, though, sadly…I’m usually met with shock, horror, or disgust when I suggest working in the community instead of a downtown or trendy-neighborhood office. I’ll keep trying, though.

At one time I was an affordable housing expert*. This was before blogging, discussion boards, social media, etc. Now, I pursue other interests.

For a while, I continued to read affordable housing trade magazines and, as they came along, visit the websites. I do so infrequently now, but I’m still interested. Funny thing, though. When I do visit, it seems I read the same articles over and over again.

Same trials and tribulations (funding program complexities and incompatibilities, gentrification, NIMBYism, lack of funding, discretionary and/or discriminatory financial underwriting criteria, zoning and other regulatory obstacles, etc., etc.). Same accolades (smart development, innovative financing, public/private partnerships with win/win outcomes, successful community organizing efforts against all odds, energy efficient, innovative project design, resident/neighborhood empowerment, community building, etc., etc.). Same arguments/advocacy for and against various proposals for improving or tweaking “the system” (better integration of housing development activity and social services delivery systems, permanent affordability, inclusionary zoning, place-based development, etc., etc.)

So far, I’ve resisted the urge to do more than just browse. But I just can’t resist the impulse to jump in here and say “I agree” with Alan Mallach.

In fact, I’d go a step further and remind that the main reason the LIHTC program is so ineffective is that it’s not an affordable rental housing program at all. Last I knew, it’s a tax-sheltered investment vehicle administered by the IRS that generates ridiculously complicated (yet insufficient) financing while saddling overworked affordable housing organizations with equally ridiculous and burdensome administrative obligations in order to guarantee financial betterment for high-wealth individuals and partnerships. Affordable housing? A noble but wholly incidental by-product.

As an infrequent visitor to these pages, I can’t be totally certain this is the first time someone with Alan Mallach’s insight, experience and credentials has questioned the efficacy of such a popular program and called for introspection in search of a better way.

If this IS the first time, let me just say …it is about time!

If it is NOT the first time, then I’d say …what, exactly, is everybody waiting for?

And by “everybody”, I mean affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators (i.e., presumably the very folks who visit websites like this more frequently than I do).

I’m particularly taken by Mr. Mallach’s call for introspection in pursuit of (and I paraphrase here): a better way to address the gap between what income-qualified, program-eligible households can afford and what it costs the private market to provide decent housing.

If such introspection ever IS undertaken by a big enough group of affordable housing experts (introspection, by the way, is typically a personal endeavor, not a group endeavor) it just might firm up the ground upon which a foundation of broad agreement can actually be reached regarding a better way to do affordable housing. But that’s a tall order.

Still… if such introspection were to lead to broad agreement (dare one hope for consensus?) on a better way to do affordable housing, that would still leave the monumental effort required to build an effective coalition among affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators to challenge the status quo and actually make it happen.

The cynic in me says it’ll never happen. It’d require an effort akin to, say, a revolution.

But just in case, I’d like to suggest that the failings of the LIHTC program may be a mere symptom, if you will, of a bigger problem.

In my view, there’s a perplexing cultural bias among affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators in favor of an affordable housing strategy that doesn’t work. The LIHTC program is just one component of that strategy.

Our nation’s affordable housing strategy, first laid out in the Affordable Housing Act of 1949, is to deliver subsidy to program-eligible, income-qualified households (whose buying power never keeps up with housing costs, whether rental or ownership) so they can afford to live in un-affordable housing. Let’s call this strategy ‘Plan A’. Truly affordable housing isn’t even on the long list (let alone the short list) of Plan A’s desired outcomes (regardless of whether HUD or the IRS is driving the boat).

Plan A’s crowning achievements are 1) to have enabled a relative handful of low and moderate income lottery winners to enjoy affordable payments while living in un-affordable homes (and in the case of ownership housing programs, windfall profits, too), and 2) to ensure a continuous and plentiful supply of housing that is un-affordable to a huge number of the very program-eligible, income-qualified households it purports to serve …many (most?) of whom are unaware such a lottery even exists.

Only a relative few U.S. households are likely to have more than a passing interest in the issue of affordable housing (rental or owned), let alone the esoteric concerns of affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators.

How can I possibly make such an outrageous assertion, you ask?

Well, because a significant majority of U.S. households own their own home. That majority has been fluctuating between 65% and 70% for the past many decades. Except for those sucked into the sub-prime lending vortex of a few years back, it’s reasonable to presume that most purchased a home they could afford. For property owners, news of rising or even skyrocketing home prices and market rents is likely viewed as a good thing. For those in the vortex, endless and large price increases were/are a must.

Making matters worse, even fewer households are likely to agree with the idea of an affordable housing ‘crisis’. This is true despite the earnest reports, surveys and data compiled by affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators …and the occasional human interest story in the Sunday newspaper.

[You know the story I’m talking about don’t you? …the one where the local affordable housing outfit helps the struggling (pick one: single parent; low-income; moderate-income; formerly homeless and/or abused individual; immigrant; refugee; parolee, etc.) buy or rent an affordable home while working 2 jobs and pursuing a college degree?]

The biggest obstacle to an effective affordable housing strategy, however, is that the vast majority of affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators actually believe (or are satisfied leaving the impression) that Plan A works.

I know this reads harsh but, seriously, how else to explain the chronic shortage of affordable housing (rental and ownership) after spending hundreds of billions of dollars over the course of nearly 70 years?

Plan A costs a fortune, addresses only a fraction of the need, is mind-bogglingly complex …and (except for a few organizations committed to permanent affordability, virtually all of which, however, must contend with the illogic of Plan A and operate with their shoelaces tied together) …produces NO affordable housing.

Who benefits from this?

Certainly, it’s not unreasonable to consider scrapping Plan A altogether? Almost any other plan would be an improvement …except a plan to put another “tool in the affordable housing toolbox”. (Can you say “let’s add another provision to the tax code”?)

I could be wrong about all of this.

But…

IF: a significant majority of households in the country think that housing is affordable enough …OR, if not, that there’s enough of it that IS affordable …OR, if neither, that affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators are actually doing something about it;

THEN: how affordable housing development practitioners, policy/opinion makers and program administrators think about the affordable housing problem – and what they resolve to do about it – may be the only thing that really matters;

ELSE: things will pretty much stay the same as they ever were.

Just sayin’.

Finally, for some introspective context, here’s a link to an article in the current double issue of The New Yorker (Feb 8 & 15) by the same Matthew Desmond referenced in Mr. Mallach’s piece: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/08/forced-out. (You may need to cut and past this URL into your browser’s address bar.)

It’s short, poignant and powerful …and devoid of charts, tables and graphs.

*An expert is a [person] who has made all the mistakes that can be made in a very narrow field – Niels Bohr

Allan Mallach is correct in his assessment that LIHTC developments are not meeting the needs of lower income households. It was never meant to do that! I was there at the beginning of this industry and am still a practicing developer of affordable housing developments.

The constant whining of a few that we must subsidize and eventually just give housing away for those low income households makes me sick. You never seem to remember that someone has to pay for all those things you don’t want the poor to have to pay for! Don’t tell me that taxing the rich is the answer, its not. You could take all of their money and still not meet the needs of all the poor that have been created in the last 8 years.

The tax credit program is complicated and its onerous and no one in their right mind would decide that they want develop tax credit housing for a business model. Its quite a crazy business when you have a stable of state employees coming up with a new plan every year or two to devise new ways to make you dance their dance to get their funding! Its really no way to run a business. It should be streamlined and objective but the QAPs that I see are moving to the left a bit more each year as they try to make the tax credit take the place of an MHA. Please, call your congressman and senator and tell them to make it stop! If they don’t stop allowing this madness, the tax credit will be totally unusable in a few years except by MHAs and Mental Health providers as they divine new ways to house their special needs.

A history lesson is in order here, that 9% credit was designed to create a public/private partnership to develop housing that was affordable for the working poor. They could live there for as long as it took to save money for a home and when they were ready, they could move from LIHTC housing into home-ownership. Thats it, pure and simple. Stop trying to change the credit to make up for the cuts that a failed HUD has had to endure for the last 30 years. There is a reason that HUD has no friends on Capitol Hill.

If you want people to be able to afford their housing, help create more jobs! To think that we need to provide never ending subsidy to evermore people to pay their housing costs is wrong. You need more and better jobs to help people make the money they need to pay the rent for their housing.

I appreciate the many thoughtful comments on my post, and would like to speak to a couple of them. Perhaps Mr. Siddons was in a bad mood when he read the piece, but I feel that I should respond just the same. One of the most fundamental aspects of any civilized society is that it makes an effort to address the needs of all of its people. Yes, that’s one reason why we pay taxes, and no, I’m under no illusions that taxing the rich is the answer. My point, which he may have missed, is that we have created a system in this country where housing is inherently too expensive for millions of families at the bottom of the income scale, and that as a result, we have condemned those millions – except for the lucky ones who win the voucher lottery – to lives of desperation and insecurity, with devastating consequences not only for themselves, but for their children and grandchildren, and for society as a whole.

Moreover, as Mr. Siddons (and perhaps some other correspondents) does not appreciate, is that the great majority of the women who (mostly) head those families are not sitting around, but are working. 74% of all single moms in the United States are working, and a lot of those who aren’t are looking for work. And showing up at a low-wage job when you can’t afford decent transportation or child care isn’t exactly the same as getting on your Google bus in downtown San Francisco. And, because of the way our wage structure and our housing cost structure are out of whack, they can’t afford decent housing. Pointing this out is not whining.

I agree with Carol Ott that there are many moderate income families that are also struggling, and agree that we could do more to meet their needs. I’m concerned about the inference, though, that meeting their needs and addressing the needs of the poor are a zero sum proposition, or that somehow the moderate income families deserve it more. Assuming we’re talking about families earning 50% to 80% of AMI, in the Baltimore area, that translates to $40K to $60K for a family of 3, who could afford rents of $1000 to $1500 per month. It strikes me that if we had the right land use regulations, some modest development incentives, and a development industry that was oriented to building plain vanilla rental housing the way they did in the 50s and 60s, those needs could be met by the market, which would be a much better way to go than trying to advocate for more subsidies. Subsidies are hard to come by, and should be targeted to those who really need them.

Nowhere in my comment did I state or infer that moderate income people were more important than low-income. Secondly, the data I use, as I live and work in Baltimore City, is city-specific One of the reasons why housing is unaffordable for so many is the reliance on MSA income data. Baltimore City’s median income is far less than that of the MSA, and therefore not relative to the problems we face in the city.

Using local data and not MSA would go a long way towards clearing up these overused misconceptions about what qualifies as “moderate income” in my city and many others.