But it was his answer to a question asking why the need for quality housing that caught my ear last week. The country, he said, needs more high-quality housing because of the shockingly unfit condition of the recruits in WWI, summed up best in a post-war poster of the era: “you cannot expect to get an A1 population out of C3 homes.” Health and housing, it turns out, have been linked through history.

Fast-forward to last week’s Healthy Neighborhoods regional convening sponsored by the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation in Oakland, Calif., where the focus had expanded beyond housing to encompass healthy neighborhoods and the opportunity for new partnerships (and new funding streams) between community development, housing, and health care to improve the “upstream” social determinants of health. As most in the room would agree, treating illness without treating the root causes of poor health is costly on many levels.

Although this intersection of health, housing, and community development is not new, what is new are incentives that are aligning today, in part due to the Affordable Care Act (ACA). As Mindy Landmark of the Sutter Health Alta Bates Summit Medical Center put it, “Health care systems now have the financial incentive to address the upstream strategies to improve community health and keep people from coming through our doors.”

One of the incentives built into ACA, for example, is accountable care organizations (ACOs) where payments are aligned with health rather than sickness. Instead of being paid based on the volume of services they provide to Medicare patients, ACOs are accountable for the health of a defined population, often their surrounding community. Those ACOs that save money while also meeting quality targets keep a portion of the savings accruing to Medicare and can choose how to invest those “savings.”

These and other incentives, said Landmark, “encourage [hospitals] to partner with people who understand the community.”

Yet, it’s hard work and there are many barriers that stand in our way. Community development and public health workers often don’t speak the same language, or even use the same acronyms. (Case in point, a CDC means a community development corporation to one group and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to another.) They often don’t understand each other’s motivations and impediments. They may still eye each other as potential competitors for funding. Further, in a world that wants fast answers, interventions to improve community health can take decades to demonstrate true impact. And in the end, any cost savings that occur frequently end up in “the wrong pocket”.

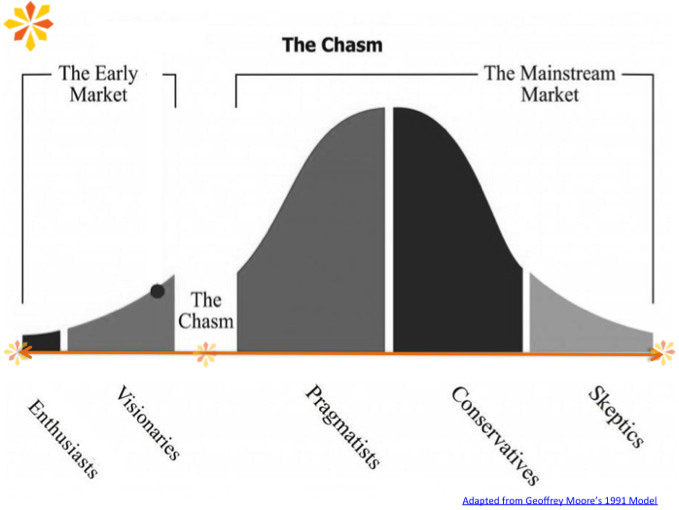

We’ve formed the Build Healthy Places Network to support collaboration across the health and community development sectors. We want to help reduce these barriers and bring people together. In his best-selling book, Crossing the Chasm, about bringing cutting-edge products to progressively larger markets, Geoffrey Moore points to the chasm that must be crossed between the early adopters—the enthusiasts and visionaries—and the mainstream market.

By highlighting success stories, sharing impact and measurement tools, and providing resources for working together, the Network aims to narrow that chasm, connecting practitioners and moving both fields toward more cross-sector collaboration. We are excited about the work at this important intersection, and would love to hear from you if you have thoughts about ways we can support your work. Please connect with us and help us share our vision: communities where all people live healthy and rewarding lives.

(Photo credit: Flickr user josh baptist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Comments