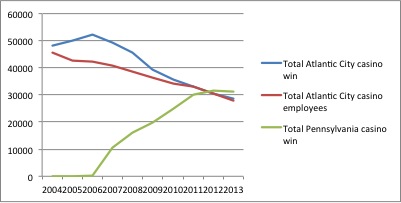

Suddenly, Atlantic City faces a $65 million budget shortfall, and is a city in crisis. No slouch at crises, New Jersey’s Governor Christie summoned 30 politicians and casino executives to a closed-door meeting in September to figure out what to do about it—without apparent results. The fact is, though, that casino revenue and employment have been plummeting in Atlantic City for a decade (see Figure below). Even before the casinos started closing, the number of casino jobs had fallen by 40 percent since 2004, and total casino revenues adjusted for inflation had dropped by over 50 percent. Meanwhile around the country, as the American Gaming (aka Gambling) Association gleefully reported, casino revenues have rebounded smartly from the recession. What we’re seeing now is the end game of a process that began the day the first casino in Atlantic City opened in 1978.

When Pennsylvania went for casinos, they were very clever: seven of the state’s twelve casinos are strung like beads along the Delaware River, keeping Pennsylvania’s gamblers at home, and drawing the many New Jerseyans and New Yorkers who live closer to Bethlehem, the Poconos or Philadelphia than they do to Atlantic City. What that is about, in turn, is that Atlantic City has utterly failed to become a place where people do more than come in, drop their money at the casino, and leave. Thirty-six years after the first casino opened its doors, most of the city is still a tired collection of low-end stores, housing projects mixed with tiny row houses, faded Victorian boardinghouses, and parking lots—lots of parking lots. It’s not terrible, to be sure. It’s fairly clean, and somebody has spent a lot of money landscaping it, but there’s nothing to keep a visitor there. Yet, the whole purpose of approving casinos was to foster the revitalization and redevelopment of Atlantic City, and the current crisis, if that’s the right word, raises a fundamental question: are casinos a way to make urban revitalization happen, or is the whole thing another shell game?

The fact is that there is zero evidence—outside, perhaps, a special case in Bethlehem, PA—that casinos are an effective tool for urban revitalization. Yes, they generate awesome numbers in terms of the dollars they take in and the jobs they create, but both jobs and numbers tend to be spread across the region, and—since casinos generate no value added—the money they collect represents a zero-sum game with other expenditures, whether its tickets to basketball games or buying groceries. Little of the money, in any event, stays in the community when we’re talking about a place as small as Atlantic City, which offers few lifestyle amenities for casino workers. Indeed, the percentage of families in poverty has risen from 23 perecent to 29 percent in Atlantic City since casinos first arrived, hardly evidence of economic improvement. Workers commute from the mainland, the profits go to companies headquartered elsewhere, and the tax revenues go to the state.

As destinations go, casinos are unusually self-contained creatures. In contrast to other tourist or visitor facilities (with the exception of Club Med), casinos don’t want you to step outside their front door. There’s a story I heard when I worked in Atlantic City in the early 1980s, when the city started giving disabled veterans permits to sell hot dogs from sidewalk carts. One enterprising vendor set up shop right outside the main entrance to one of the casinos, selling hot dogs for 75 cents. The casino owners tried to shoo him off, but when he wouldn’t budge, they went out, bought their own cart, set it up right inside the entrance, hired somebody to cook hot dogs, and sold them for 50 cents each.

Finally, if casinos don’t generate urban revitalization, and don’t really add that much to the economy, why do states love them so much? The fact is, they are state tax revenue cash cows. There’s a basic economic rule that if you give someone a monopoly, you can tax them at a much higher rate than someone who has to compete in an open market. Outside of Las Vegas, every casino in the United States is part of a monopoly of some sort, either limited to a particular area like Atlantic City, or given exclusive rights to a geographic territory, as in Pennsylvania. Maybe Atlantic City will come up with a new way of rebuilding their economy. If it does, I doubt that it’ll be the casinos leading the charge.

For an in-depth look by the author at the economic and social impacts of casino gambling published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, see this review.

Photo credit: Alan Mallach

Comments