Rents have become increasingly unaffordable in New York City. NYC has been in a housing crisis for decades. A housing crisis, defined as under 5 percent vacancy rate, in NYC triggers an elaborate system of rent regulation.

Rent regulation is not a subsidy program, but a system in which rents are regulated and determined by an appointed Rent Guidelines Board. Under rent regulation, tenants receive a guaranteed lease renewal and can compel landlords to provide essential services, such as water, heat, and repairs.

Unlike public and subsidized housing, rent regulation costs the city, state, and federal government almost nothing to operate, beyond a small regulatory apparatus. Rent regulation is a virtually no-cost affordable housing strategy that houses millions of low- and moderate-income tenants in nearly 1 million rental units citywide.

Rent-regulated housing has by and large disappeared in the rest of the country, and in New York City, where rent regulation remains a critical mainstay of affordable housing, landlords and the real estate industry continually mount attacks on the system, seeking to undermine it in favor of market-rate housing.

Tenants & Neighbors is a citywide membership organization of rent regulated tenants. Our members are low-income, moderate-income, seniors, youth, and immigrants, and live in all five boroughs. Though diverse in age, race, class, and ethnicity/nationality, they all tell the same story. They are trying to figure out how they can stay in their homes and communities, as their rent climbs to an ever-increasing proportion of their income. Many of them have seen their neighborhoods change rapidly as New York City has increasingly become a city for the wealthy, leaving them and their neighbors wondering just how much longer they will be able to call this city their home.

The attack on rent-regulated housing and New York City’s breakneck gentrification are inextricably linked.

New York City has 8 million residents, approximately 2.5 million of whom are rent-stabilized tenants. (An additional 32,000 live in “rent controlled” housing, a legacy program.)

Over the past 20 years, the city has lost over 100,000 rent regulated units to a process called vacancy decontrol: when the monthly rent reaches $2,500 and the unit becomes vacant, the unit becomes market-rate, and is no longer subject to rent regulation. Due to vacancy decontrol, there is great incentive for owners to increase rents to $2,500 and then to harass tenants to vacate. In neighborhoods that were once working class and middle class, rents in formerly regulated units are reaching $3–4,000 and more, far more than even middle-income residents can afford.

How are rents raised in rent-regulated apartments? Loopholes in the New York state rent laws allow landlords to raise rents upon vacancy and to add a portion of the costs of major capital improvements permanently onto the tenants’ rent. (Landlords frequently add more than they are legally permitted.)

Most importantly, rents are raised by the annual decisions of the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB), a nine-member mayor-appointed board. The RGB is tasked with looking at landlord’s costs, tenant’s incomes, and any other relevant data to determine what the increase should be. In its 45-year history, the board has always voted to increase rents while the affordability crisis has gone from bad to worse.

Over the past six years, under the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the RGB raised one-year leases an average of 3.25 percent per year, and two-year leases an average of 6.3 percent.

After new appointments by Mayor Bill De Blasio, pressure by many new City Council members, and massive organizing by the tenant movement, the RGB voted last month for the lowest increase in its history: 1 percent for one-year leases and 2.75 percent for two-year leases.

Though the increases were low, the mayor, the tenant movement, and many elected officials representing rent-stabilized tenants had called for a rent freeze, which would have helped to redress the substantial increases of the Bloomberg years that took place in the depths of the Great Recession. There was enormous disappointment that the RGB did not vote for the rent freeze.

Affordable housing policy shouldn't be just about building new affordable housing. It should be about making sure that the affordable housing resources we have don’t become so unaffordable that tenants get displaced. Currently, over 30 percent of rent-regulated tenants are paying half or more of their income toward rent.

If there isn’t a rent freeze next year, or the year after, approximately 750,000 tenants will likely be under threat of displacement in the next few years. This is our potential reality in a city where landlords have seen their profits rise for eight consecutive years; this year their profits rose 9.6 percent. Landlords were overcompensated for years under the previous administration, leading to the worst affordability crisis the city has ever seen. Through voting for an increase this year, the RGB continued its current trajectory and low- and moderate-income tenants will continue subsidizing landlords’ profit. The Rent Guidelines Board must vote for a rent freeze next year; affordable and diverse neighborhoods in New York City depend on it.

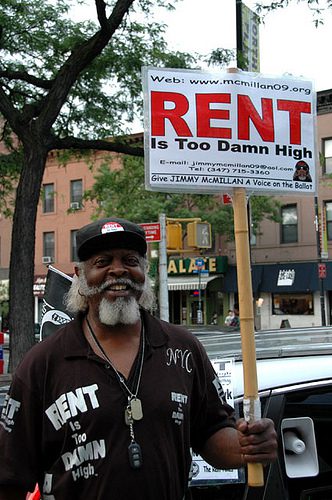

(Photo: Jimmy McMillan, founder of the Rent Is Too High political party. Photo credit: Matt Law, CC BY-NC-ND.)

I grew up in New York and lived in the city as an adult.

There is no more toxic CAUSE of high rents than rent control.

Yes. Rent control causes higher rents.

In direct violation of the fundamental laws of supply and demand, rent control and rent stabilization have kept SOME rents in New York City artificially low.

The inevitable result of such market meddling, if you know anything about economics, is a shortage.

And that’s what New York has, a shortage of those artificially cheap apartments.

Beyond the rent controlled apartments, the lopsided demand that shortage has created in the rest of the city’s housing market is unnaturally high rents. The abolition of rent control in New York would bring LOWER rents for most apartment dwellers looking for homes as landlords could start charging real world market rates for their units. The introduction (back) into the real world market of all those apartments would eventually reduce the price of the commodity just as happens when you add any new supply into a commodity market.

Of course doing away with rent control overnight would be a horrific hardship for apartment dwellers who have, sometimes for generations, benefited from unfairly suppressed rents. For occupied units, rent control should probably be phased out over a reasonable period of years.

Rent control or stabilization of vacant apartments should be abolished immediately.

It would take years for the market to stabilize after decades of distortion by government intrusion but the end result would be a fairer rental market. ….and probably a lot of BETTER apartments as it suddenly became worthwhile for landlords to invest in upgrading them. It could even provide a jobs stimulus as workers were employed to improve long neglected units.