My organization, the Maryland ACLU, recently helped launch a new website, www.housingmobility.org. Who needs another housing website? In fact, yes, there is a need.

Until now, housing mobility has not had a home on the web and is covered sporadically, if at all, by other housing sites sponsored by foundations or the affordable housing or community development industries. When it exists, the coverage is sometimes sensationalized, often superficial, and frequently misinformed. Rarely do housing mobility practitioners get to shape the message about what they do, their successes, and their challenges.

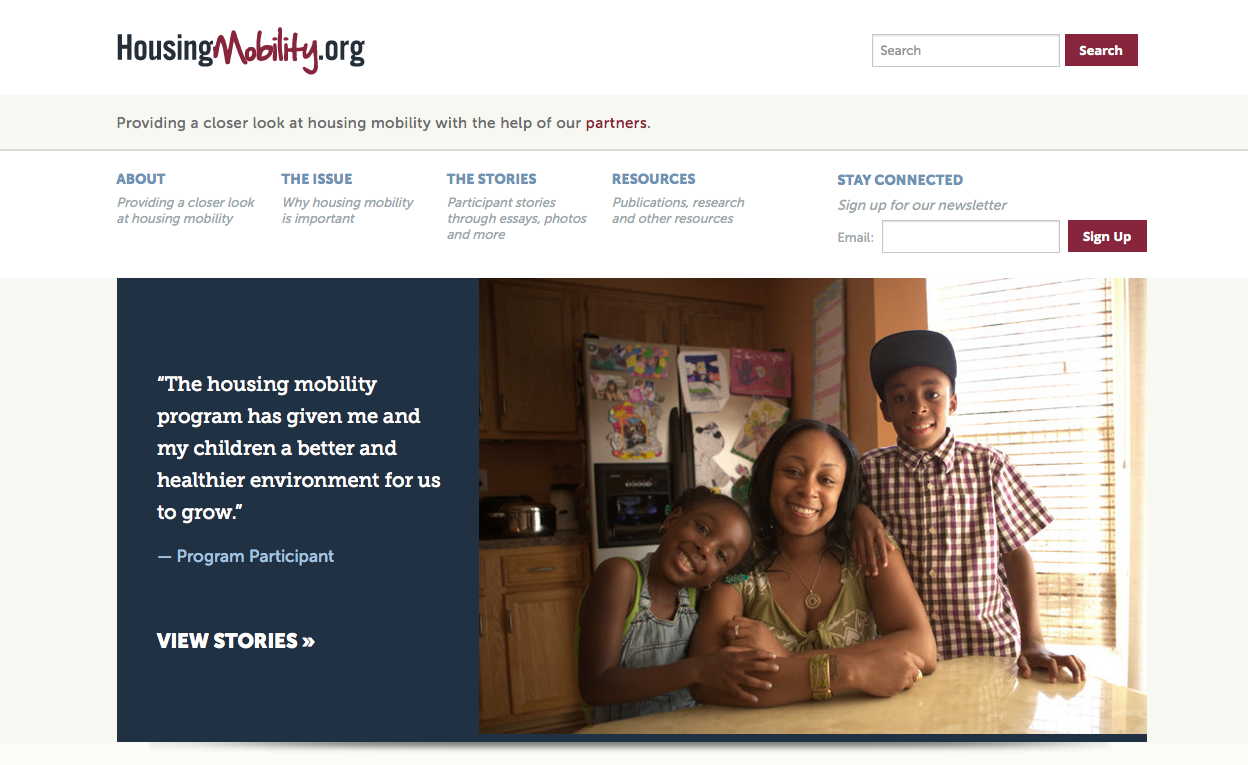

It is rarer still to hear the voice of parents or kids participating in housing mobility programs. Logistically, it is difficult for voucher tenants to be heard in the policy arena or within their local housing authorities. That is even more true for families in mobility programs. There is a dominant narrative from organized public housing tenant activists in the policy arena, but the community of HUD-assisted residents is far from monolithic.

Housingmobility.org aims to address this gap. It includes housing mobility program profiles and video, audio and photos of families participating in regional housing mobility programs from across the country. The site also includes a comprehensive resource library with the latest social science research, legal advocacy, best practices, and policy analysis in this growing field.

Hear Taneeka Richardson, for example, describe the impact of the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program, operated by Metropolitan Baltimore Quadel, on her life and the opportunities for her children. She says, “my kids would not be able to have the opportunities they have now, for a fact, if we were still living in the city.” Ms. Richardson, who has gone from a GED, to community college, to the University of Maryland, College Park, to graduate school, during the nine years she has been living in Howard County, Maryland, describes herself as a “firm believer in living in areas of opportunity…it does inspire you.”

Listen carefully as Rhonda Curtis describes her journey from eviction, which she calls, “the worst experience,” to living in HUD subsidized housing in West Baltimore where she felt “almost like a prisoner in our own home” and then to a HOPE VI project in East Baltimore, where her daughter was almost caught in crossfire and she plotted to get out. Ms. Curtis talks about starting over in a new community in suburban Baltimore County: “I’m ready for a new beginning, this is a new chapter in my life, and I’m going to take it for all its got. I’m going to ride this train until the wheels fall off because I don’t plan on going back.”

Nicole Smith says that she found out about the Baltimore mobility program from an aunt, who did not want to move. But Ms. Smith says she took the information from her aunt and ran with it. A mobility move isn’t necessarily right for every family, but almost everyone wants to know they have a choice.

For decades, many of the families living in public housing and distressed neighborhoods have been telling us of their desire to escape the violence and despair gripping their neighborhoods. Invariably, the number one reason families apply to mobility programs is the desire for a safer neighborhood and better environment for raising children. What could be more basic or compelling?

Yet, the voices of these families have largely gone unheard, or perhaps just ignored. In their stories are “inconvenient truths” about our nation that few on the left or right want to hear.

It’s time to start listening. Converging evidence from the medical and social sciences is telling us the same inconvenient truths. Children growing up in poverty, in the midst of distressed neighborhoods and exposed to community violence, are at risk of real harms. This is what their parents have been trying to tell us all along.

It is crucial that we all work to improve these communities. But in the meantime parents should have the chance to move to a safer environment that offers real opportunities for their children.

“Yet, the voices of these families have largely gone unheard, or perhaps just ignored. In their stories are “inconvenient truths” about our nation that few on the left or right want to hear.”

I am sorry to read this statement from Ms. Samuels because my experience over the past 30 years is very different. Yes, the tension of place-base and mobility exist. I would argue that our advocacy and work can be place-based and people-centered that recognizes the mobility is as much our fight for fair housing as the right to remain in place-based struggles.

I was on the Making Connections-Providence Family Economic Success team ( funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation) where this struggle was felt in our work to improve and stabilze five neighborhoods with a place-based approach. Yet, the reality of the financial crisis of starting in 2007 in our neighborhoods uprooted many families as foreclosures rose. We recognized that the work still required a place-based focus while supporting families that moved outside the five neighborhoods. Housing mobility is a tool and a resource for our families. Just as the battle around place-based ( see the Leaning In post on equitable development this week too). I fully embrace a place-based, people-centered approach to CED work. Housing mobility is part of that approach. Not better, not worse in our struggle to improve the places and lives of our families and communities.