This is Part 1 in a series about the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty. Click here for Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.

—-

In honor of the 50th Anniversary of the War on Poverty, I’m going to do a series of posts about poverty with a bigger-picture, retrospective look.

For this first post, I’m going to start with the changing racial demographics of poverty. But then I’m going to try to bridge to a bigger point about how we think about poverty and then try to debunk some of the current rhetoric around the legacy of anti-poverty programs.

The Changing Racial/Ethnic Demographics of Poverty

Fifty years ago, the racial/ethnic demographics of poverty (and the country as a whole) were much more starkly black and white.

In 1959 (based upon the census’s analysis of the 1960 decennial data), the racial breakdown of people living under the federal defined poverty line was:

- Black: 26 percent

- White: 73 percent

- Not Black or White: 1 percent

More recently, in 2012 (per latest 1-year ACS data), the racial breakdown of the poverty population was:

- Black: 22 percent

- White (non-Hispanic): 44 percent

- Not Black or White (non-Hispanic): 35 percent

These numbers are a little misleading in that, in 1960, the census did not track people of “Hispanic” origin and so the 1960s “White” category almost surely contains significant numbers of people who would have identified as Hispanic.

However, in the 1970 Census (the first time “Hispanic” was in a decennial census), less than 5 percent of the general population identified as Hispanic. This is compared with 17 percent of the general population in 2012. That is, the Latino/Hispanic population has grown dramatically in the past five decades and the larger point still stands. Fifty years ago, the U.S. poverty population was largely black and white. The current poverty population is much more diverse, with over a third of the people in poverty being neither black nor white.

In other pieces I have argued and will argue again in the future that the changing demographics of poverty means that we need to re-think paradigms of race and poverty and adjust (in both big and small ways) policies and programs that serve those with economic need in order to better reach a more diverse poverty population.

I have argued and will argue again in the future that the continuing disproportionate numbers of African Americans in poverty is part of a body of evidence demonstrating that we have not adequately addressed/redressed the specific history or current-day realities of racism against black people.

But here, in this piece, I’m going for something more philosophical.

Not the Same River

“You cannot step twice into the same stream.” – Heraclitus

Looking at the changed demographics of the poverty population is an entry point into seeing how deeply the poverty population has changed over the decades. People talk about the poverty population as if it is the exact same people who are poor today as it was 50 years ago. But, looking at the racial demographics, you can see that a good chunk—at least a third—is different.

But it’s more than that. For all intents and purposes, it is a completely different population. There is probably a number of people who were poor at the onset of the War on Poverty and who are still poor. But this is not a high number, relative to the overall poverty population. Millions of people who were poor in 1960—whether by pulling up their own bootstraps or by luck or by direct intervention via War on Poverty programs—have been lifted out of poverty. Millions of people who were poor in 1960—particularly the elder poor—are simply dead. Their ranks have been refilled with new people.

It seems obvious when you say it directly, but it is not something that has fully reached how we think and talk about the poverty statistic. If we hear that the poverty population increased from 45 million to 47 million from one year to the next, without thinking about it too deeply, we tend to think that the exact same 45 million people who were poor in the previous year are still poor and that there are an additional 2 million poor people.

But the population isn’t so static. From year to year, there are births and deaths. Some families at the margins of poverty—particularly the working poor—may dip in and out of poverty from year to year depending upon very small changes in circumstance (e.g., ability to get overtime or find supplemental part time work, changes in health of family members).

I don’t want to make too fine a point of it because I still believe that economic mobility—particularly in terms of obstacles for poor folks to climb the economic ladder—is far from what it should be (70 percent of people raised in poverty never make it to the middle income). But, the poverty population is dynamic. There are always inflows and outflows. And, over the sweep of 50 years, it’s not the same river.

The Legacy of the War on Poverty

Paul Ryan, one of the leading critics of the legacy of the War on Poverty, argues that because there are still so many people in poverty, the War on Poverty has failed. This line of argument, among other fallacies, relies on the assumption that poverty has been a static population, unchanging despite all the money that we throw at it. But it is not same river. And the demographic category that I led with—race—is only one dimension in which the poverty population is different.

As another example, seniors are a much smaller proportion of the poverty population than they would be if not for the War on Poverty. Before the War on Poverty, senior citizens had double the poverty rate of non-elderly adults. Since then, the poverty rate of seniors has pretty consistently been about half of non-elderly adults. This is in large part due to the creation of Medicare and Medicaid and the expansion of Social Security, which happened as part of the War on Poverty.

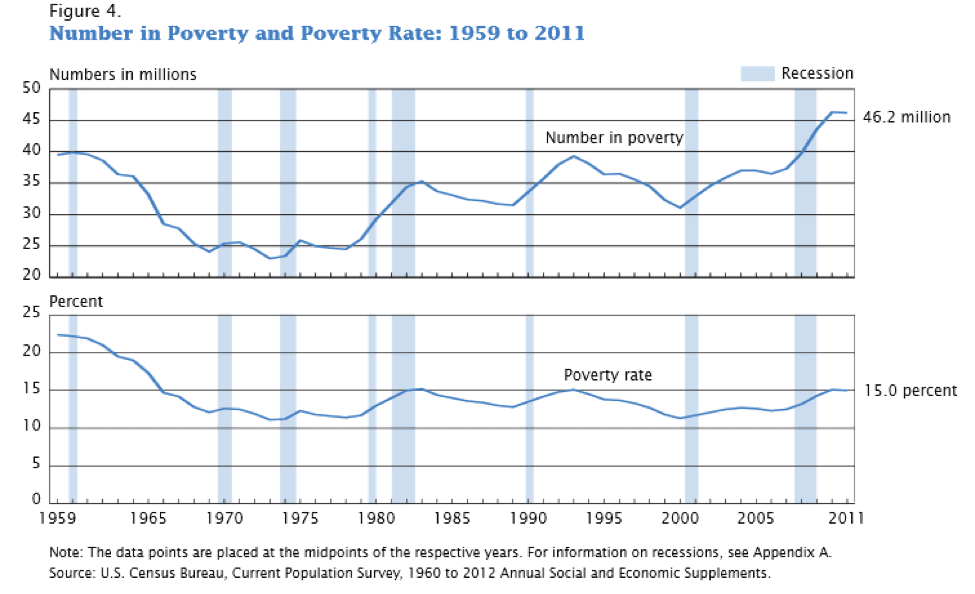

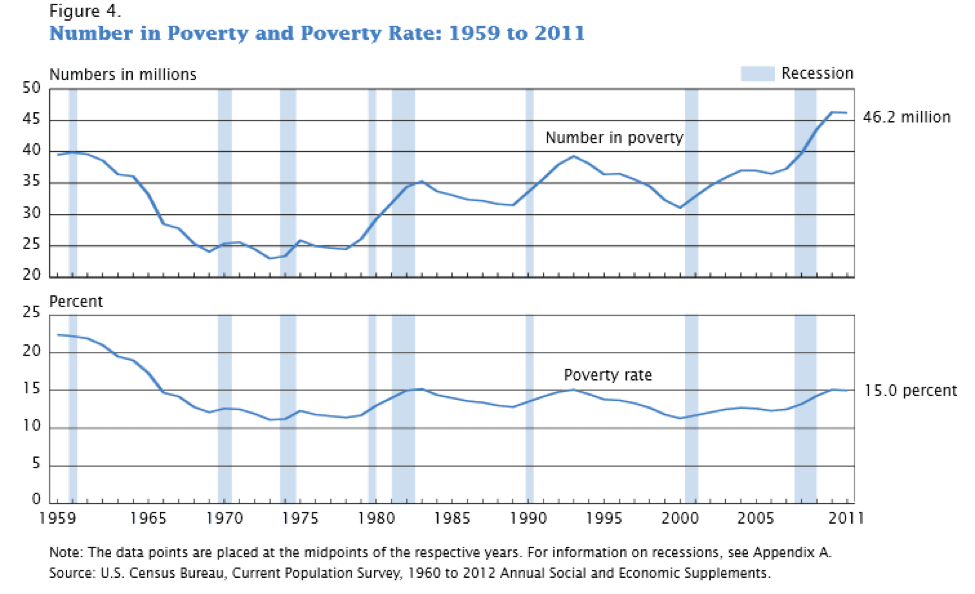

Despite not having vanquished poverty in the battlefield (declaring WAR! on poverty was stupid), the War on Poverty has been a success. Absent the War on Poverty programs, it is estimated that the current poverty rate would be double what it is now. The War on Poverty, and other anti-poverty programs that grew from it, have helped millions of people out of poverty. But, the ranks of poor people are constantly being replenished.

Despite our best efforts, there continue to be people who live in poverty. This is because these anti-poverty programs have been designed to address needs/problems on an individualized basis and are not about addressing more fundamental limitations on income/job distribution.

One big thing is that there simply aren’t enough high quality jobs for everyone to have one. But this is no fault of the War on Poverty. It’s a simple issue of scarcity/capitalism. And, through our macroeconomic policies, we actively discourage full employment.

Therefore, we should know that, for structural economic reasons, we will always have a portion of the population that is unemployed or low-income. Given these boundaries, the issue shouldn’t be whether or not poverty persists. Instead, we should be focusing on whether opportunities are open to all; whether poverty is unfairly distributed on the basis of race, gender, faith, sexuality, etc.; whether we are doing all that we should to limit the number of poor people; whether we are doing enough to assure a basic quality of life for the people that will inevitably be poor.

By these measures, we still have a lot more to do. But the mere continued presence of poor people doesn’t invalidate what has been accomplished to date. We have made progress. And, if we can continue to muster the will, we will continue to make more progress.

I am afraid this article is way too simplistic to shed much light on the issue of poverty and potential ways to better address it. Here are just a few more complicated aspects that mitigate against Mr. Ishimatsu’s comments:

1. Of course in 50 years the people who were poor then are not the one’s who are poor today…the question is whether their children and grandchildren continue to constitute the larger proportion of those in poverty. If so, then there is reason to believe that the so-called “war on Poverty” has not been a effective program…at least from a cost-for-success point of view.

2.A major aspect of poverty in the US, particularly among the rise of Hispanics, is immigration. Few countries in the world import poverty to the extent the US does. Legal and illegal immigrants preponderantly bring their own poverty with them…they don’t inherit here. And it stresses the system’s ability to effectively deal with those ever-increasing numbers.

3. The not-so-subtle poke at the supposed capitalistic intent to develop scarcity so as to maintain low labor costs plays into the typical class-warfare and conspiracy of power thinking that has kept communistic countries in the backwater of economics. It’s easy to blame conspiracy and argue for socialistic reform, except that where it such reform has been fully implemented the results haven’t proved as helpful as promised.

4. The greater reality of continued failure to raise people out of poverty resides in three associated issues:

A. We have raised the level of what constitutes poverty to the point that for some people it is easier to live in an acceptably reduced economic circumstance than take the effort and risk to do better.

B. We have so gutted the educational system of truly producing a workable education that would lead to better ability to cope with a constantly changing economic field that only strongly committed family structure can overcome it….and too many of governmental programs do little to lift and support that needed family structure.

C. The unfortunate and failed “War on Drugs” has created an artificial sub-culture that attracts too many in the lower economic areas to turn to the “quick” riches of the drug business rather than seeking the necessary education and development of marketable skills for the standard market.

These and other related commensurate issues work in concert to make poverty a hard nut to crack. To blame one well-intentioned but deeply flawed government program; or alternatively to take a Marxist(equally flawed) critique of capitalism and propagate conspiracy theories against power-brokers will do little in effectively addressing the problem.

The need to address real issues might just lay a foundation for doing something of merit. But continuing to throw political barbs from philosophical stances probably isn’t going to do much of value.