Confession time: Despite the work that I do, when I began using AirBnB as a business traveler, I didn't think much about its affordable housing implications. To me, it was a chance to save a little money on hotels, an excuse to get out and see the neighborhoods a little, maybe meet some locals.

The “sharing economy” as many people like to call it makes some intutitive sense. I remembered how much trouble my parents had finding someone to rent the house I grew up in when my dad took a sabbatical and we went to England for 6 months. Perhaps AirBnB would have made it easier, much as it did for the family off in Australia for a year or so whose Philadelphia row house I stayed in during my recent trip to Philadelphia. I know someone who is able to afford the house she owns in a gentrfying area of Queens through AirBnB rentals of her spare bedroom. I was fascinating by the listing of a woman in Chicago who appears to be running what works out to a small hostel in her residence in a decidedly non-posh neighborhood, with international guests gushing about all the people they met while staying there and the value of getting out of the tourist areas of the city.

It did give me pause, I'll say, to notice multiple whole apartments for rent by the same user. I did get the feeling that in Atlanta I was possibly part of a chain of guests subsidizing a single college student's living in a large apartment that could easily have fit a family. And I did wonder how the neighbors felt about him having a lockbox with his keys in the stairwell of their building, and buzzing people in remotely.

But still, when it came to the fight over AirBnB's legality in New York City, my first thought was to side with the company (or at least, with the hosts, which is actually not at all the same thing). Ok, I thought, I guess folks making a full time business out of it should pay hotel tax, but surely you're not going to go after individual hosts?

I hadn't really grasped the depth of the potential problem until I read about what's happening San Fransicso though.

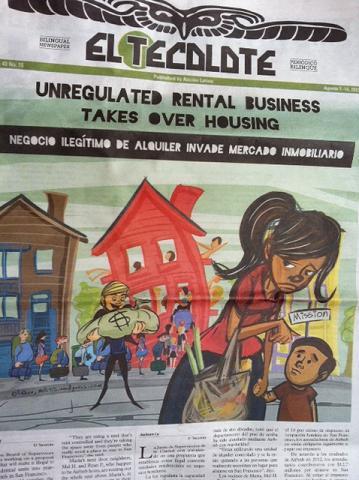

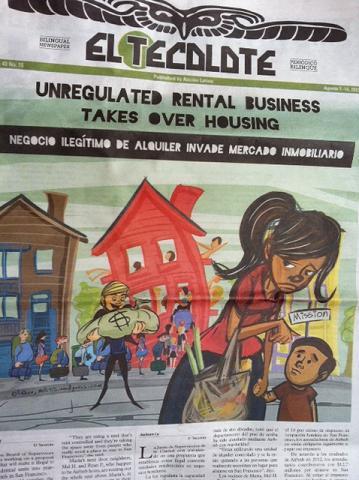

According to reporting by the Bay Guardian and El Tecolote, AirBnB rentals are so lucrative in San Francisco that they are affecting the supply of apartments as units are pulled off the rental market and put into the easier-to-manage tourist market. Many are illegal sublets of rent controlled apartments. In others, rent controlled tenants are evicted not to make way for owners, but to make way for tourists. In a city that is already struggling with a wave of condo-conversion evictions, more evictions and loss of rental units is a problem. (And it takes a rare thing to unite tenant and landlord advocates against it.)

Knowing the effects of an affordable housing shortage in an area like that, from homelessness and displacement to sprawl and grueling commutes: Ouch.

Meanwhile in San Francsico, AirBnB has been ordered to pay the city's transient occupancy tax (technically it is co-responsible with its hosts, but clearly it's the one with the ability to calculate and collect it) and is just point blank refusing to do so—not the kind of behavior we want to see out of a “sharing economy” company. (The Bay Guardian points out that some of AirBnB's competitors do collect the tax.)

I understand the company's argument that tourists who spend less on accomodations and who are staying in neighborhoods will spend more at local businesses, but would you really exempt a low-budget hotel chain that located in a neighborhood commerical district for the same reason?

So lost municipal revenue, increased evictions, lost affordable housing. Not something I actually want to side with.

Of course, the affordable housing angle is a complicated question when you involve the perspective of hosts, not just the company: many New Yorkers say AirBnB income from sharing their place of residence is giving them housing stability in a market that would otherwise have forced them out—something households have done through illegal longer term subletting from time immemorial. Renting a room as opposed to a whole apartment may be illegal subletting, but at least it doesn't remove rental units from the market.

I suppose one question is if you limited AirBnB to just those listings that cause less harm, would its business model survive?

AirBnB and similar companies are clearly a disruptive technology that will require some renegotiated rules, tax applications, and enforcement mechanisms that try to strike a balance between all the various interests afoot. That's only going to work, though, if the company will negotiate and the cities have some leverage to make them.

Has AirBnB affected the housing market where you are? Are you afraid it will?

[Nov. 1: edited to add: This Atlantic Cities piece on invisible work gives an interesting gloss on this question too.]

I admit to the same ambivalence, having used AirBnB, but I am getting annoyed at AirBnB’s “we are above the law” attitude.

AirBnB guests could pay hotel taxes, I am willing to do that. You’d think that a company that claims to be all about “sharing” could do that.

There could be limits on the number of days per month, or per year, that an apartment could be rented out for overnight use. If an apartment owner wants to go over that limit, they’d need to get a permit as a bed and breakfast.

What it would take would be AirBnB working with the cities, instead of stonewalling them.

I’m curious when you use the word “disruptive”, what you think is being disrupted. Those who rent multiple apartments are causing issues for those who are attempting to survive through this type of service. No I don’t think a small hotel is the same, not even the same as the people who rent multiple units. I’m not sure I see much empathy here for the folks who are struggling. And I di see how this could be an issue as far as housing shortage, but only if the majority of people doing it were landlords renting multiple units. And that can certainly be addressed by strengthening rental legislation. I think we have become a people who instead of looking for solutions, look to choose sides of an argument, thereby perpetuating division instead of working together to find solutions. In your article, it seems you have already made the decision that taxing everyone is the only solution. A shame.

The essence of a free market economy is demand and supply with competition. I don’t see anything wrong when one finds a cheaper way to provide accommodation for those needing them as AirBnB does. It is the hotels that should differentiate their services and make their accommodation superior. As for affordable housing, it is a systemic policy issue that law makers can address if citizens insist that it must be fixed.