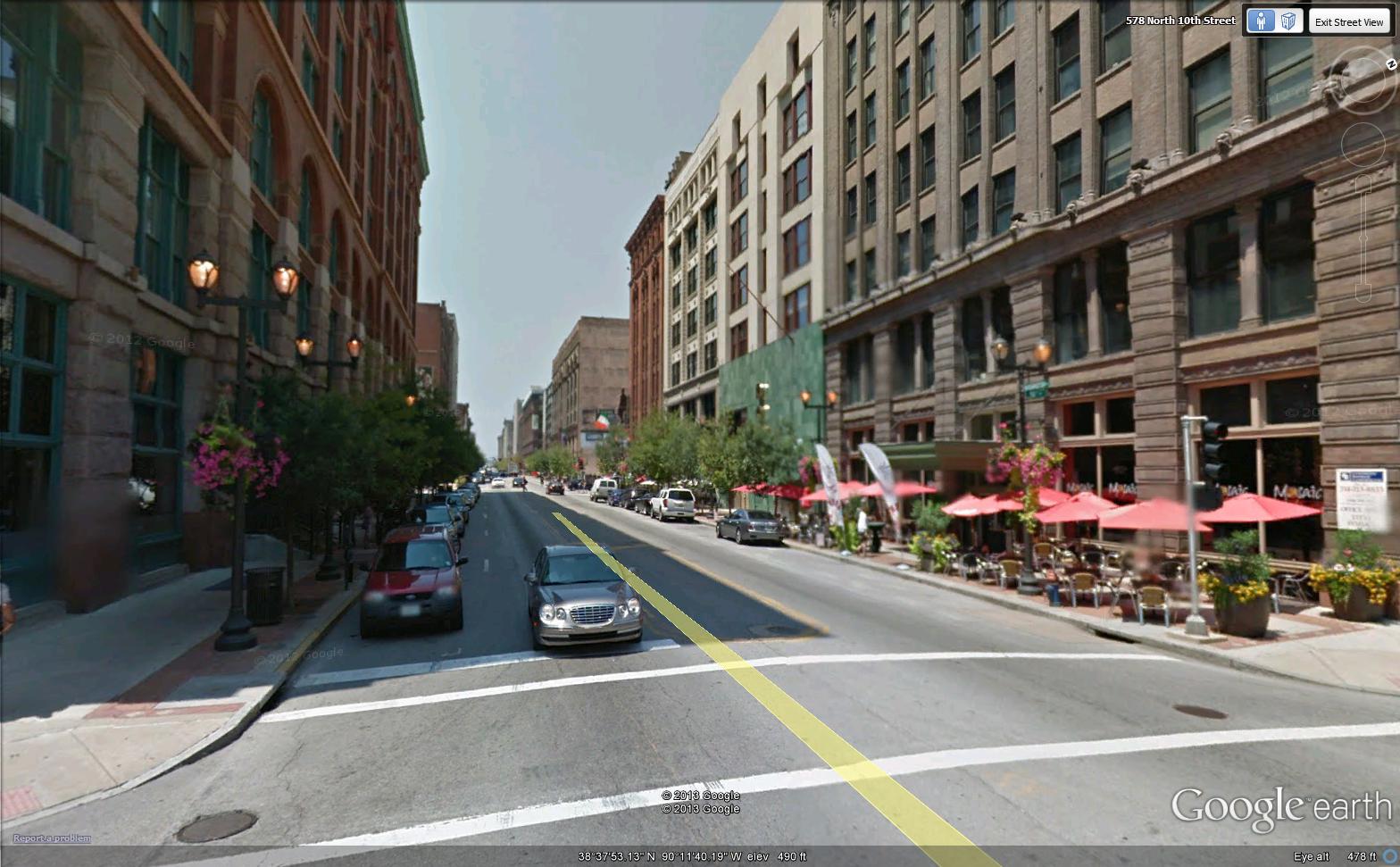

Washington Ave St. Louis (credit: Google Earth)

As I continue to wrestle with the future of cities and urban neighborhoods, and about how to go about reversing the decline that seems to face so many of them, I find myself increasingly concerned about how the future of our cities and their neighborhoods will be affected by the demographic changes that are going on in the United States. Downtowns may be resurging, but are our urban neighborhoods, which are a much larger portion of the area of cities, built to attract and serve the sorts of households that now predominate?

Let’s look at the city of St. Louis, though it’s pretty much the same in other cities.

In 1960, over half of all the housing units in St. Louis were occupied by married couples, and over half of them were raising children. Fast forward to 2011, and less than a quarter of the housing units in the city were occupied by married couples, and only 1 out of 10 by married couples raising children.

At the same time, the share of single individuals in the city’s population nearly doubled. Meanwhile, single head families – many of whom were women raising children – did not increase that much, but all the same went from less than a quarter of all families to half.

|

St. Louis Households |

1960 |

1960 |

2011 |

2011 |

|

All family households |

70% |

|

48% |

|

|

Married couples |

|

56% |

|

24% |

|

Married couples with children |

|

32% |

|

10% |

|

Single-head families |

|

14% |

|

24% |

|

Non-family households |

30% |

|

52% |

|

|

Single individuals |

|

22% |

|

43% |

|

Other non-family households |

|

8% |

|

9% |

These trends may not be exactly startling – although when I visit a city like St. Louis and ask what percentage of their households are married couples raising children, people typically will guess high, saying “about a quarter” or “maybe 20 percent.”

The point is, these numbers have powerful implications for what is happening in urban neighborhoods. Nationally, 20 percent of American households are married couples raising children, about twice the percentage in most cities, but well below what it was only a couple of decades ago.

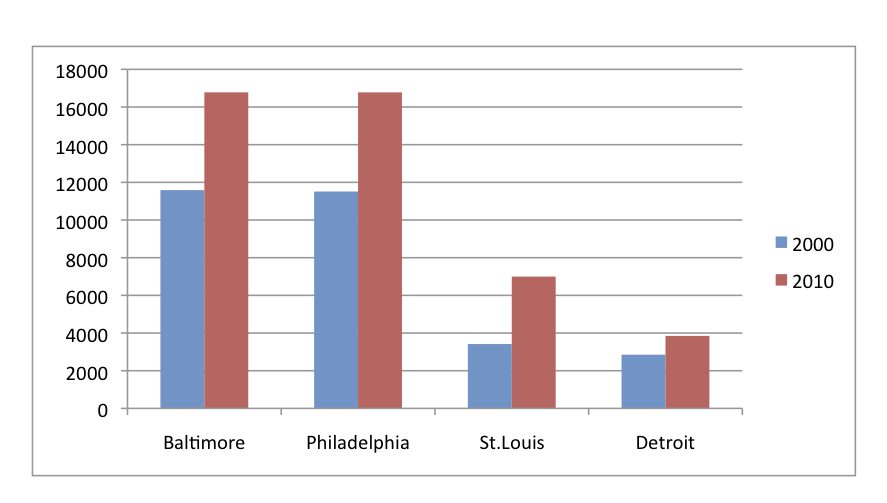

This is what’s driving downtown revitalization. Somebody, I forget whom, has said that “downtowns are the low-hanging fruit of urban revitalization.” He or she was right. With millions more young singles and pre-, post-, or non-childrearing couples in the population, and with cultural trends favoring urban living – at least up to a point – there is a natural market for any downtown that is visually appealing, walkable, and with enough jobs in and around it so people can pay for their loft and their lattes. Downtown areas in St. Louis, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and even Detroit are gaining population, as the graph below shows. Meanwhile, in each of these cities, the rest of the city lost population.

Change in Downtown Population in Selected Cities 2000-2010

This is pretty small potatoes, though. Of these four cities, in 2010 the downtown contained 2 percent of the city’s population in Baltimore and St. Louis, about 1 percent in Philadelphia, and about ½ of 1 percent in Detroit. The other 98–99 percent live in what can generically be called the city’s neighborhoods. That’s where the difficulties arise.

With few exceptions, America’s urban residential neighborhoods were built for a single purpose: to provide a place for married couples to raise children. They varied enormously otherwise. Some were developed with grand houses for the wealthy, but most with modest houses, often for people who worked in the nearby factories. In New England and Northern New Jersey, a lot of houses were two and three family houses, where the owner could live on one floor, and rent out the others. From Trenton, N.J., south to Richmond, row houses were the norm, while in the Midwest single family detached houses predominated. But they all served the same purpose.

Rethinking the Neighborhood

What will the future of these neighborhoods be? While they were walkable, in the sense that no house was usually more than a few blocks from the nearest streetcar line or the nearest convenience store, they’re not the kind of walkable environment that draws the same people who flock to downtowns. A few areas, mainly those with higher density, distinguished historical housing stock, and excellent access to downtown, have been colonized by upscale families. Those families include quite a number of child-rearing couples who send their children to private schools. Those are the exceptions – cities never had that many of that type of neighborhood.

What about the rest, the majority of neighborhoods that do not have those features? In some cities, they have become immigrant destinations, particularly for Latino immigrants who are still somewhat more likely to be raising children than other ethnic communities. Latino immigrants have repopulated southwest Detroit and Newark’s Ironbound, along with large parts of Trenton that were Italian neighborhoods through the 1980s.

That still leaves a lot of neighborhoods, particularly in cities where immigration has been limited – like St. Louis or Cleveland – not to mention the open question whether those Latino immigrants who prosper, or their children, will stay in these urban neighborhoods, or whether they will move to the suburbs as have most of the white or African-American households who’ve had the ability to do so.

People like me talk a great deal about creating communities of choice, about drawing demand into urban neighborhoods to foster the diversity and market strength that seem to be needed to create strong, healthy neighborhoods. That is important, and needs to be done.

But this is where the heavy hand of demographics comes into the picture. Where is the demand going to come from to sustain our urban neighborhoods, and is there enough demand to go around? Or, should we be doing more thinking about building different types of community to reflect the different demographics of 21st century America?

And if we do want to build different types of community, what would they look like? And, how would we pay for them?

This is interesting. I have found that my neighborhood, which is not downtown, but does have a walkable commercial strip and a good bus connection to it, in a small city that has been slowly losing population, is thriving. And it’s thriving with families with children, many of whom love the two-family houses that predominate because they can house grandparents on the other floor, or get some extra income so they can spend more time with their kids. It’s not an affluent area, and the parents we know send their kids to a mix of public, private, and homeschool—but I think public is the most common.

Do you think we are just a fluke? Or is there possibly one neighborhood like ours in most cities where the families with children who want to be living urban concentrate? (I can think of three in Albany, really.)

There are things we need to address. Violence and school performance is a major concern of any parent of school age children. A study cited in last months Mother Jones Magazine says the decline of our schools and the violence experienced by all inner cities is directly attributable to lead poisoning.

So we regulate against lead. We place a burden on the home owner but do not address this corporate problem with corporate action. So owners are in a position where they avoid knowing of lead contamination. The result is a low level problem that never gets addressed, Lead in the soil is not addressed at all.

Even having addressed these how do we deal with obsolescent housing stock. No one lives in three rooms. Is a two family conversion the most cost effective use of resources? How can we preserve low income housing while updating for today’s needs?