Americans have just wrapped up another ugly presidential election. Even with the outcome, as Gar Alperovitz reminds us in America Beyond Capitalism, the progressive achievements of the 20th century and progressive aspirations in the 21st face rocky times ahead.

The continued shrinking of labor will give the wealthiest Americans, individually and through their corporate personhoods, a growing opportunity to chip away the remnants of the New Deal and the Great Society. We should prepare to work longer hours, for less pay and more limited benefits, and to retire in abject poverty. Our hours to participate in small-d democracy will become more scarce, and democracy itself will increasingly be like this year’s political conventions — theatrical performances orchestrated by those with money. Meanwhile, any remaining sense of happiness and stability will be upended by environmental crises like climate change, social crises triggered by widening inequality, and political crises deepened by all the local power we’ve surrendered over the years to global free-trade regimes.

Yet it’s the very severity of these crises and their intractability, Alperovitz argues, that might just move Americans to consider more radical options. After we have exhausted tinkering with private health insurance through half-baked reforms like Obamacare, we finally might be willing to entertain a coherent single payer system. Once we recognize that we cannot possibly pay for Social Security and Medicare, we might decide that rather than cut our benefits we’ll impose more serious taxes on the wealthy.

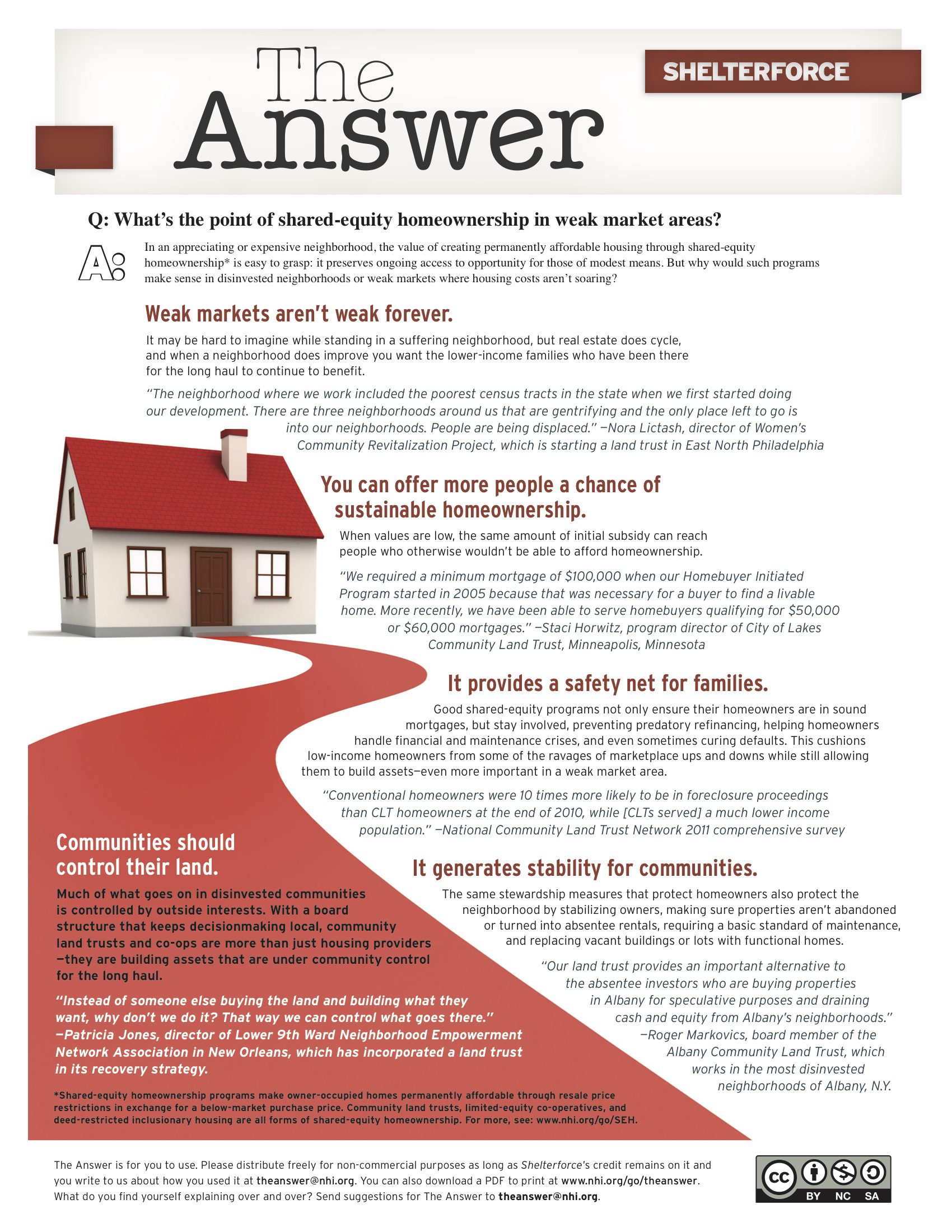

Alperovitz finds hope beneath the political surface. Across the country, progressives — often with the support of principled conservatives — are reinventing business, government, and civic life, through what he calls the Pluralistic Commonwealth. Cutting-edge cooperatives, small businesses, worker-owned firms, social enterprises, community development corporations, and municipally owned entities are providing competitive alternatives to the Fortune 500 economy. These new community-based businesses not only are raising the bar on labor and environmental standards but also democratizing the ownership of capital and experimenting with shorter work weeks. Meanwhile creative states are stepping into the voids left by federal inaction, whether it’s California leading auto mileage standards, Vermont moving ahead with single payer health care, or North Dakota running its own public bank. And as U.S. demographics shift away from the white males who long dominated our political culture, space will open up for new leaders, new strategies, and a new politics.

Three features of America Beyond Capitalism make it an especially valuable book for classes and study groups. First, Alperovitz is a remarkably thorough scholar. Some 75 dense pages of notes underscore how many years he and his colleagues spent culling books, articles, and the Internet for literally hundreds of creative proposals. It’s hard to think of another book that provides such a thorough overview of the literature of economic alternatives.

Second, Alperovitz is not just an abstract theorist. He worked his early professional years on Capitol Hill. He later helped Youngstown, Ohio, consider the possibility of buying a recently closed steel mill in 1977. Thirty years later, he worked with community activists in Cleveland to design and deploy an American version of the Mondragon Cooperatives, anchored in the Evergreen Laundry. These real world experiences, all of which had important successes and shortcomings, give the analysis a welcome tone of humility and cautiousness.

Third, while a self-avowed Wisconsin-bred progressive, Alperovitz is remarkably non-ideological, and urges us to reject the worst elements of both capitalism and socialism. Clintonian New Democrats, Wellstone liberals, Ron Paul populists, and even Reagan small-government conservatives will find proposals here that are exciting and thought-provoking. It’s hard to imagine another contemporary scholar who, on a two-page spread, could so credibly weave together the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, Herbert Marcuse, and John Adams!

Every reader will surely also find lots to quibble with. Personally, I find Alperovitz’s critique of centralization persuasive, but not his arguments that regional governance (which barely exists in the United States) is more promising than local government (which is thriving). I agree that unless we change the demands of work and family, Americans will be unlikely to participate in day-to-day democracy; but I worry that many citizens today, in the absence of greater education and mobilization, would use a shorter work week to become couch potatoes rather than activists. I find his proposals for redistributing corporate stock obsolete (not to mention politically farfetched) now that recent crowdfunding reforms make it easier for small local businesses to create new stock. I prefer to abandon Wall Street, not redistribute it. Nor is the top-down character of these proposals consistent with Alperovitz’s (or my) faith in decentralization. At the end of the day, any redistributionist policies may well have to be led by the states, communities, and even cooperatives.

These are the kinds of friendly debates Alperovitz and I have been having for more than 20 years, since we worked shoulder-to-shoulder at the Institute for Policy Studies in the early 1990s. The genius of Alperovitz, and this book, is that no reader exposed to so many ideas can possibly come away without rethinking where he or she stands or without pondering some new ideas he or she might embrace. Above all, Alperovitz is one of the nation’s most skillful teachers.

The book was mostly written before 2005, though several new chapters for this edition resituate the arguments for today. The first edition was remarkably prescient. Alperovitz foresaw that sooner or later the 99 percent would find political legs in increasing taxes on the top 1 percent. If the book’s thesis is right, Occupy Wall Street is just the beginning of a new chapter in American history where wealth is distributed more fairly as a prerequisite for a decent society and real democracy.

Alperovitz counsels us to look past short-term wins and losses in elections — and many of both lie ahead — and encourages readers to focus on the slow, patient work of rebuilding America, one family, one business, and one community at a time.

Comments