Shortly after President Obama’s second inaugural address calling for collective action on our greatest national challenges, I happened to speak with someone curious about Community Solutions' work in two high poverty neighborhoods. I explained that the Brownsville Partnership in New York City’s Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, and the Northeast Neighborhood Partnership in Hartford, CT, were collective efforts involving multiple organizations coordinating their actions to transform these left-behind communities into safer, healthier, more prosperous places.

“But what kind of organization are you?” he asked.

“We coordinate collective action” I said.

“But are you a housing developer? A social services agency? What exactly are you?” he pressed.

It was clear that there was no file in his brain for “coordinator of collective action”.

While it is becoming clearer that the only way forward to solving the most complex and destructive problems facing our communities, nation, and planet is through new forms of creative collaboration, we haven’t yet settled on the language to describe this process, and the organizational structures needed to support this movement are still emerging. We can acknowledge the many elements of our social welfare system that are broken, and the limitations of familiar economic development and case management strategies for reducing poverty, but have a hard time abandoning the old language, and questioning the old structures to make way for the new ideas and organizations needed.

The concept of “multiples” refers to ideas that bubble up at the same time in different places, or in science, discoveries made independently at roughly the same time. While Alexander Graham Bell was inventing the telephone, for instance, so was one Elisha Gray, who got to the patent office later that same day. Ideas whose “time has come” seem to have that quality of emerging simultaneously in response to clear needs and as next steps made possible by other discoveries. Such is the moment now it seems for collective strategies for challenging poverty and strengthening communities.

In a widely shared 2011 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, authors John Kania and Mark Kramer described the notion of “collective impact” as an emerging strategy for educational reform (STRIVE), environmental action (Elizabeth River Project) ,and combating childhood obesity (Shape Up). They defined collective impact as cross-sector coordination to achieve common, measurable goals directed at the root causes of problems in contrast to isolated programs. Collective approaches are inherently more efficient. They enable existing resources to be used in more targeted ways, reduce redundancy and begin to expose and weed out those programs and ideas that are too expensive to be justified or simply don’t work.

The collective impact concept is also surfacing in community development, and the potential is highlighted in an important new book, Investing in What Works for America’s Communities published in September by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. With many local partners we are applying these concepts on the ground in neighborhoods of extreme disadvantage, and discovering other efforts, such as the Magnolia Place Community Initiative in Los Angeles, that are on the same road. And the approach is proving transformative to the lives of vulnerable homeless people and their communities. Volunteers, government agencies and not for profits in over 180 communities are working collectively to end chronic homelessness through the 100,000 Homes Campaign.

Collective action to solve complex problems is proving to be an idea whose time has come, but perhaps with any shift, the new reality precedes the language needed to describe it. Let’s not let that get in the way, but get to work on defining a new vocabulary for this essential process, and on creating the structures to support collaborative local problem solving. Who else is interested in working on this? I’d love to hear from you: [email protected].

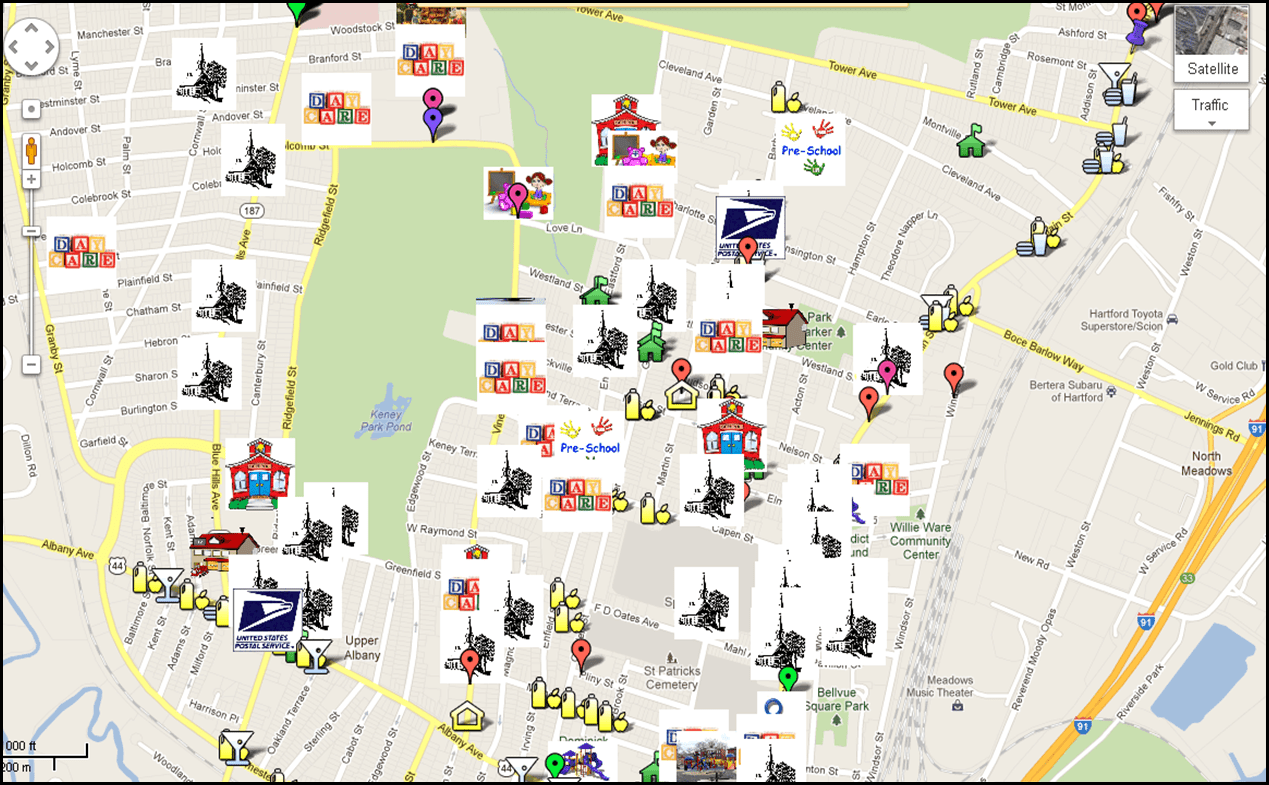

Image: A community asset map detailing services, organizations and recources throughout Northeast Hartford. / Credit: Community Solutions staff

Comments