There's an utterly fascinating recent post by John Roman on the Metrotrends Blog of the Urban Institute called “Gentrification Will Reduce Crime and Violence—But Only if Poor People Stay.”

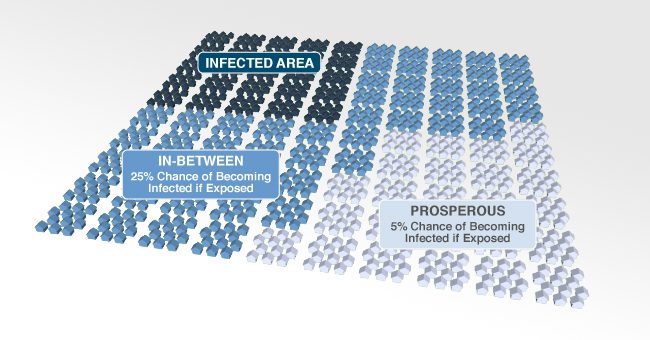

The thesis is that if you take a public health approach to crime and violence, and consider it contagious, that having prosperous, and therefore presumably less susceptable to contagion, areas abutting poorer areas will slow the spread of crime, and therefore the total amount of it in a larger area. Roman writes:

While we know that isolating our poorest residents is really bad for them, it turns out that segregating the rich and poor leads to the worst outcomes for a city as a whole. Economic integration, where the rich and poor live side by side, leads to the safest cities.

I'm inclined to agree with statement, as I think would Dr. Mindy Fullilove, who argues forcefully for “unsorting” our cities and preventing displacement as a prerequisite for improving public health and stable communities.

But I have to admit to being a little confused as to how Roman's maps represent either gentrification or economic integration or anti displacement.

At least in his blog post, his first example involves an area “infected” with crime, and a prosperous area (mostly “immune”), with a barrier between them of an “inbetween” area that is susceptible to being “infected,” and thus the crime spreads. Then he flips it and puts the prosperous area in the middle instead, showing that this arrangement from an epidemiological standpoint has a better outcome.

Unless he's talking about very fine grained areas, this doesn't exactly sound like economic integration to me. In plenty of cities and regions there are wealthy and poor neighborhoods or towns nearby in central areas with less extremely segregated neighborhoods on the fringes.

I do realize he was taking an extreme example as a thought experiment, in which there were no remedies for crime except moving where people live. So perhaps I'm being too literal, but I guess I'd like to see this modeling taken further—what happens if you create a tipping point by various actions to reduce crime in the “infected” area such that some people with means move in, but take measures to ensure those who are already there and want to stay are not displaced? What if we do a thought experiment about a region of varied neighborhoods that are not distinguished from each other by the mix of incomes present?

Policy Change?

In any case, I'm still very interested to see the question being framed this way, and I'm curious to know if this sort of thinking will gain steam and lead to different policy and program discussions. I have long said that the binary conversations about whether we focus on helping people leave distressed neighborhoods or improving those neighborhoods too often leave out the crucial third point of the triangle—preventing involuntary displacement from places that are changing, whether slowly by gentrification or wholesale by redevelopment.

If venerable research groups like the Urban Institute start speaking up against displacement will it become easier to give anti-displacement strategies their due and remember to consider the displacement consequences of other programs and projects? I'd like to think so.

Comments