The United States is emerging from one of the most extensive and painful economic crises in memory. It is well established that housing markets were at the heart of this crisis, and millions of American households lost, or continue to lose, their homes to foreclosure. While the recent housing crisis is not to be overlooked, far too many rural residents have struggled with housing problems and inadequacies for years, if not decades, before the national crisis hit. These are among of the key findings from the Housing Assistance Council’s recently released Taking Stock report, which is a comprehensive overview of social, economic, and housing characteristics of rural Americans. HAC presents Taking Stock every 10 years after the release of the decennial Census.

The Housing Crisis Hit Rural America Too . . . .

Over the past decade the United States economy fell into one of the most severe economic recessions in a half century. Unemployment rates reached generational highs, and substantial wealth and equity have been stripped from home values following the housing market crash. Millions of American households had trouble meeting their mortgage payments and lost their homes, while many still face foreclosure or eviction.

But Many Rural Households and Communities Struggled with Basic Housing Challenges Long Before the National Crisis

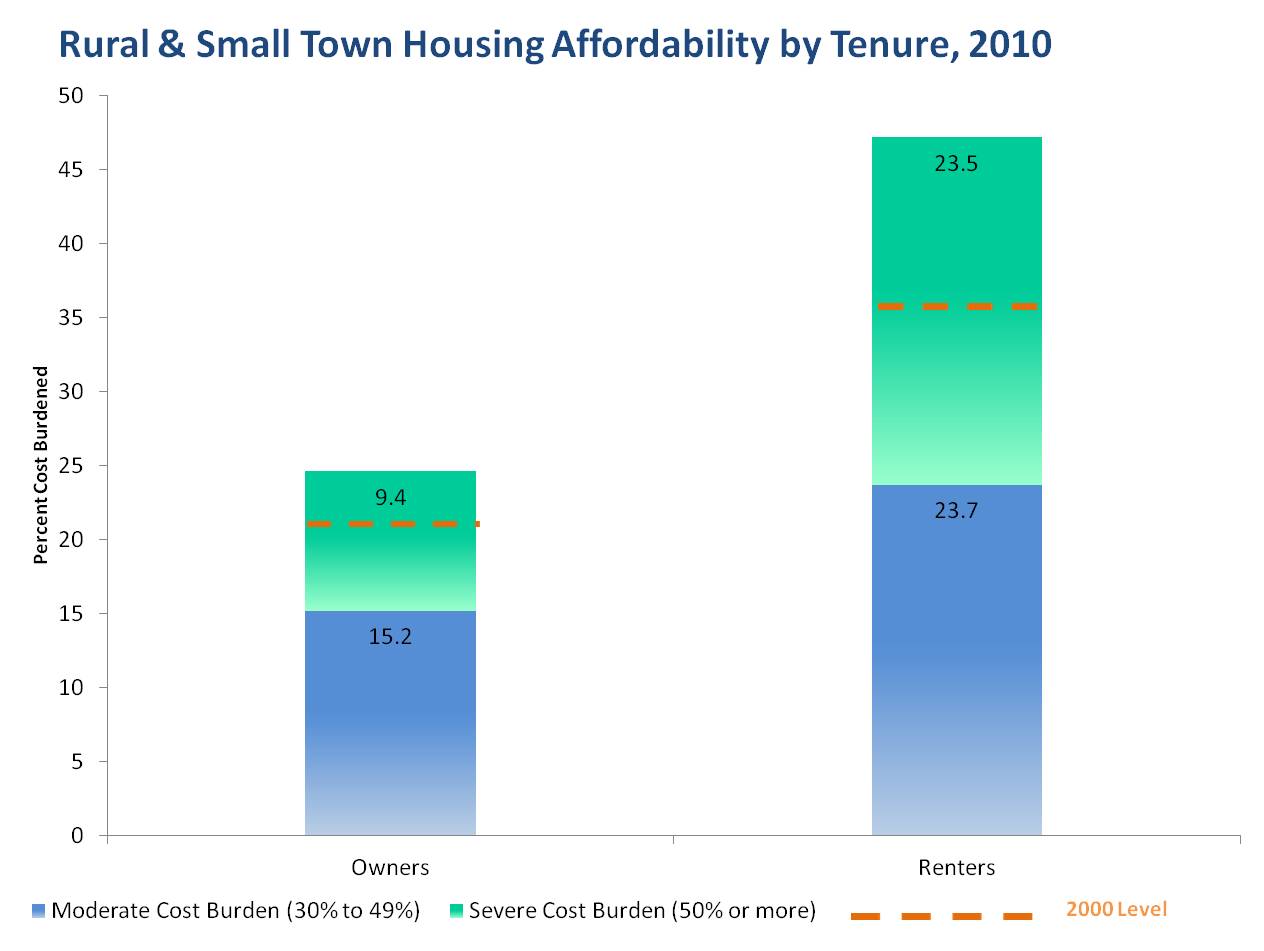

Affordability has become the most significant housing challenge in rural America, especially for low-income households and renters. Despite the fact that housing costs are lower in rural areas, an increasing number of rural households find it difficult to pay their monthly housing expenses. Over 7 million rural households – three in ten – pay more than 30 percent of their monthly incomes toward housing costs and are considered “cost-burdened.” The incidence of rural and small town housing cost burden increased by a full six percentage points between 2000 and 2010. Housing affordability problems are especially problematic for renters. Approximately 47 percent of rural renters are cost burdened, and nearly half of them are paying more than 50 percent of their monthly incomes for housing.

Crowded homes, defined as those with more than one occupant per room, are slightly less common in rural regions and small towns than in the nation as a whole. Household crowding, however, is more prevalent among some rural groups and communities than others. On Native American lands, 8.8 percent of homes are crowded. Crowding rates for Hispanic households are three times the overall rural rate, and Hispanics occupy over 30 percent of crowded housing units in rural and small town areas. Household crowding in rural areas is often an invisible form of homelessness as some rural households “double up” with friends or relatives in reaction to adverse economic or social situations, or to escape substandard housing conditions.

Housing problems are often not isolated and in many cases are compounded by the combination of inadequacies related to affordability, housing quality, and crowding. Over half of rural and small town households with multiple problems of cost, quality, or crowding are renters.

There are still far too many housing problems in rural America. But there has also been a precipitous decline in the most egregious housing inadequacies such as dilapidated homes and outhouses. The reasons for this progress are varied. But a relatively modest federal investment has directly improved the housing conditions for millions of rural Americans. Recognizing this progress is important as new and more complicated constraints of affordability and housing distress have emerged. If anything, the past decade has taught us the importance of housing to our nation’s economy, communities, and families. The nation’s fiscal outlook is complicated, but public sector investment and involvement are crucial to healing our housing markets and ensuring their long-term health while recognizing that all communities, rural and urban, need attention and investment.

Comments