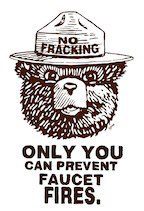

This past Monday, I attended a large anti-fracking rally here in Albany, NY, aimed at convincing Governor Cuomo to ban the practice. For those not living in an area wracked by this controversy, fracking is a way to access natural gas by injecting large amounts of chemicals horizontally through a shale layer of the earth. It poisons water, creates toxic byproducts, and even causes small earthquakes. It is perhaps one of the most contentious issues in New York state at the moment.

Of course as is so often the case with things that will enrich a large company at the expense of someone's air or water, it is being sold to struggling rural communities as a source of jobs and income for leaseholders, many of whom are having difficulty making ends meet on land that has been in their farms for generations.

Not only have the jobs promised in states like Pennsylvania not materialized, as many people at the rally pointed out, there are also all those jobs that rely on not despoiling the waterways of New York (and all those downstream).

This seems analagous to many of the Good Jobs First type fights we've seen in other areas, where we are told that economic development means pushing back against environmental regulations and labor standards and exempting corporations from paying taxes in order to lure them to set up shop. This race to the bottom has been proven to not gain workers anything over and over, but apparently that's a fight we have to keep repeating.

As we wrote about in the last issue of Shelterforce, California's voters resoundingly rejected the “jobs!” claim made for a dirty energy bill in favor of their health and lasting jobs in the clean energy economy. What do the anti-fracking advocates have to learn from that fight? It would be great to see some of the folks who have resisted having their interests pitted against each other in other contexts step up to lend their voice to the fracking fight.

The protest also, as any protest tends to do, made me thoughtful about organizing tactics—particularly about engaging the people who are disrupted in their day by such an event, and can ill afford to be. How does a movement raise hell when it needs to and still confront the reality that there's often a certain privilege in being able to go out and protest? I have no easy answers for how to address that, but I noodled yesterday about some ideas for how to approach some pieces of the question.

In any case, it seems like that as long as our communities are struggling for jobs, health, and quality of life, fracking—and similar challenges from energy companies trying not to give up on fossil fuel because they already have these reserves on their books—are going to become an issue for more and more of us.

Comments