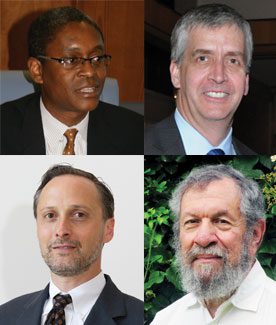

(top, l-r) Dr. Raphael Bostic, Chris Herbert, (bottom, l-r) Jeffrey Lubell Alan Mallach,

Taking part in this discussion with Shelterforce editor Miriam Axel-Lute and NHI executive director Harold Simon are: Dr. Raphael Bostic, outgoing assistant secretary of Policy Research and Development at HUD; Chris Herbert of the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard; Alan Mallach, fellow of NHI, Center for Community Progress and the Brookings Institution; Jeff Lubell of the Center for Housing Policy; and Janneke Ratcliffe of University of North Carolina.

Miriam Axel-Lute: Is affordability getting better or worse?

Alan Mallach: It’s an incredibly mixed bag. The variation between markets in this country is just enormous, and I suspect it’s greater than before the bust. Think of a market like Las Vegas now, where last spring, the housing and planning people from the city said that, basically, they didn’t want to see anymore tax credit housing because, as far as they could tell at this point, it was the people roughly from 35 percent of AMI or down who are the ones who had the real affordability problems and that, in fact, they had a whole bunch of tax credit projects on a watch list for potential failure, because they were losing ground. Essentially, they weren’t effectively competing with private market stuff in the same price range.

Then, at the other end, you’ve got markets, especially some of the major coastal markets, where it’s pretty clear that private market rental housing is rebounding, rents are rising, and the affordability issue, is as great, if not greater.

Chris Herbert: I think that there is a question about where we need new supply, or whether we need new supply. But in terms of what’s happened with affordability, last year, across the 100 largest markets, we looked at the share [of households] paying more than 50 percent of their income for housing over the course of the last decade, and it was up everywhere. There are variations in markets, and some markets obviously fare much worse than others, but the direction was the same.

And a lot of it comes down to the fact that income inequality has been growing. Incomes among renters fell across over the last decade. And that was not a story that was isolated to certain markets. It’s true that house prices have fallen and rents did soften, but rents didn’t fall that much.

Alan Mallach: No, not as much.

Chris Herbert: The CPI is a crude measure, but it showed really just a trivial decline. And part of it was because rents didn’t boom as much as they did on the price side. Price-to-rent ratios got out of whack, and so there wasn’t as much of a correction needed. And you had the homeownership crisis pushing renter household growth to the highest level it’s been in decades. We’ve had more than five million renters added over the last decade, which is the most since the ’70s, and it’s mostly happened in the last five years.

So I do think that affordability, while we can parse where it’s better or where it’s worse, it’s gotten worse everywhere, and mostly because of the different diverging trends in rents and incomes that are pretty consistent.

Jeff Lubell: We found somewhat similar information just looking at 2008 to 2010, a period in which housing prices were going down, and we found affordability got worse. So it really is important to distinguish between the cost of housing today if you’re going out into the marketplace and how that relates to incomes versus the actual cost that people are paying who haven’t moved. Everyone’s been hunkered down. They haven’t moved.

We found that rents have gone up by about 4 percent for working families, and incomes have gone down by 4 percent for working renters. Both of those push you in the direction of worsening affordability. And for owners, the two-year change in housing costs was only 2 percent among working families, a reduction, whereas incomes were down 5 percent.

So it may look great right now in theory to look at new housing, or the costs of existing housing and say that, as a share of incomes, it looks affordable. But for the folks who are stuck paying much higher shares of their income based on pre-recession housing prices and housing costs, that’s not a reality.

Miriam Axel-Lute: So Jeff, are you mostly talking about owners, or are you also talking about renters in terms of being stuck paying previous prices?

Jeff Lubell: Owners are the ones who are paying housing costs based on pre-recession prices. There’s been an over-emphasis on looking at the price of housing today as if people were completely free to move into the homeownership market when, in fact, they’re not completely free because they may be burdened with negative equity, or they may be unable to get a mortgage because their credit has declined, and credit supply has tightened.

And you can try to wave those problems away, but the reality is that, as soon as those problems go away, prices will start to creep back up, because demand will be back. So we’re basically, I think, in an artificial situation right now, and will be there for a while. And there may be a window in which people can take advantage of low prices due to the housing—due to the foreclosure overhang, and when credit starts to warm up and before it’s all been worked through, but that window is going to disappear pretty quickly.

Raphael Bostic: I actually think that the ownership story is a bit more complicated. It is certainly true that there are some burdens, but we’re going to see the working through hopefully in a more accelerated way of some of these mortgages that were unsustainable, or close to unsustainable.

Alan Mallach: On the owner piece, things may work out eventually, although I think the question of how the credit supply is made available is still a big question mark, with all the debates going on over the future of Fannie and Freddie and what constitutes a qualified mortgage and so forth.

But one way or another, I think that’s going to be a very slow sort of sorting out. So my guess would be that, on the ownership side, prices are likely to start moving only gradually and slowly. I think the double-digit increases that we saw in the early years of the last decade are not likely to come back for a long time, if ever.

Chris Herbert: The experience in places like California and the Northeast that had previous housing bubbles, although not of the same magnitude, is that house prices take a long time to develop any kind of an acceleration up.

But I do think that we can also overstate—I mean, the prices will probably stay low, but the cost of credit, while it seems it is historically low now, it’s not as low as it seems, and it could go up quickly. The headline interest rates don’t take into account the loan level price adjustments that the GSEs are imposing. So if you’re a borrower with not as much money down, with a worse credit score, if you have loan features like an adjustable rate or the like, then you’re going to be facing significantly higher interest rates than those headline rates.

And on top of that, you also have mortgage insurance premiums. FHA has been an affordable option, but FHA is also starting to try to take a position to encourage the private sector to come back in. They’ve announced increases in their insurance premiums that are going to take place this summer. That’s going to push the up-front premium up to 1.75 percent of the loan amount, and the annual premium to just under 1 percent. And so, if you’re able to get a mortgage at 4 percent, you still have to pay another 1 percent on top of that for your mortgage insurance premium if you’re a buyer with less than 20 percent down in the FHA world.

And those rates are only going to go up. As the economy expands, we’re going to see general rise in interest rates. We’re already seeing mortgage rates rise. So that window we have where, at least on the mortgage cost side, are as low as they are, is probably going to close. And that can have a significant effect on closing off the affordability of homeownership for folks with little savings for a downpayment.

Harold Simon: If you have that on the financing side, what will happen on the price side of homes? Will that drive prices lower? Will there be an equilibrium there?

Alan Mallach: I don’t know if it’ll drive prices lower, but assuming that there is a positive trend in the economy and increases in household formation, it would certainly act as a drag on prices rising the way they might otherwise if borrowing costs and credit availability were constant.

Miriam Axel-Lute: We spoke at the beginning about the differentiation between coastal markets and a place like Las Vegas. And even if we agree that there are affordability issues in each place, they’re still markedly different. How do we talk about and think about the differences between hot markets and distressed markets in terms of affordability?

Alan Mallach: I think a big issue is the question of the extent of existing supply and the extent to which one could use the existing supply as a vehicle for creating affordable housing options rather than new production. If you look at some of those high-pressure coastal markets, they’re starting to show significant declines in supply, and some are showing fairly tight rental vacancy rates and so forth. Those are areas where I think there’s a strong case for production strategies, particularly on the rental side.

In the other markets we’re talking about over-supply still. And I think for some time to come, because of the slow increases in household formation and the extent of the foreclosure overhang in places like these distressed Sun Belt and Rust Belt areas.

That’s where I think the question of actually trying to figure out how to maximize the use of the existing supply really becomes much more important. I mean, it’s important in all cases, but more to the exclusion of additional production.

Jeff Lubell: One of the issues that needs to be considered here is not just looking at the market as a whole, but trying to think about sub-areas within each market, and trying to understand the long-term trends that are going to affect the demand for housing in particular sub-areas within a market.

And it’s difficult to look out five, 10 years, but if we’re talking about whether or not we invest in a production strategy versus a demand strategy, I do think we need to have a longer look. And that means trying to think about some of the long-term trends in the age of the population. For example more older adults, more younger adults without children, both tenure groups that, 10-to-one, live somewhat closer in, not always central city but perhaps first-string suburb. The rising price of gas is [also] going to increase demand for housing close in.

My fear is that in particular areas, both within markets we think of as strong markets and also some that we don’t necessarily think of as strong markets but aren’t in the weak category, there’s going to be increased demand for housing near transit stations, near job centers, places where transaction costs are low and where there’s sort of more of a mixed-income, mixed-use kind of approach. And that’s going to end up increasing the price of housing in those places over the long-term, because we do not do a very good job responding with supply to increases in demand in infill settings.

And here we really need to think about how do you lock up affordability over the long-term to ensure that families of all incomes will have access to those kinds of neighborhoods. So it is a transition from the market side to the policy side, but it requires us, within each metro area, to understand the demographic trends, what type of housing they want, and in particular will they want to live in particular places within that metro area.

Housing is unaffordable largely due to zoning (height, minimum setback restrictions, segregation of residential, commercial and institutional), impact fees (too low for low-density, too high for intensification/infill), and property taxes (based primarily on the value of the building, rather than the value or size of the land). In addition, apartments are taxed a higher rate of other types of dwelling units (because it is considered to be a business), in spite of the cost to provide services per dwelling unit is lower. Cost of living should incorporate both housing and transportation costs, as if one’s common destinations are within walking distance, transportation costs are close to zero.

Pithy, insightful, and chock full of useful ideas. Great job Shelterforce!

I’m particularly intrigued by the notion of a “pass-through” LIHTC for 2-4 family homeowners to help preserve market-rate affordable rental units. Over the next decade or two as low-density homeownership neighborhoods in NYC recover from the shock of the foreclosure crisis, I think we’re going to need some strategies to keep these homeowners (and their rental units) stable. I think we’re facing a wave of homeowners who will manage to squeak by and keep their homes, but who will suffer from underwater mortgages, poor credit, tight cash flows, and no other cash assets at their disposal. So what happens when they need to replace the roof or the boiler? They won’t be good candidates for accessing any conventional financing, that’s for sure. A straightforward loan fund (like HEMAP) is certainly an option — but a tax based incentive that’s simple for the homeowner to access could also prove a compelling tool.

Anyway, great food for thought!