The population of King Island has all moved to Nome on the mainland about 90 miles away, but walrus-hunting provides an important link to their roots.

They say the walruses turn a pink color when they are ready to “haul out” onto the sea ice where they can be hunted; watching the sky and sea for signs of the coming walrus migration is an art still passed on from elders to the young generation.

But the effects of climate change have wreaked havoc with Arctic weather conditions that while always extreme and highly changeable, could be read like a book by Natives with centuries of experience and highly detailed language to describe different types of ice, wind and other climate conditions.

Now, Native Alaskans across the state say, they can no longer predict important climactic changes and events like they used to, leading some to freeze to death caught in storms or stranded on ice; or face starvation as their traditional hunts are interrupted.

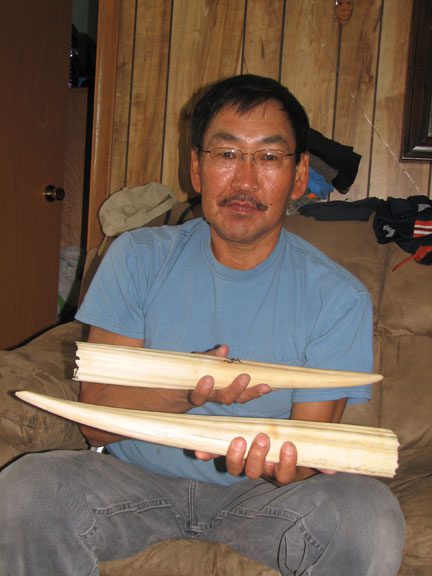

Around the 1960s most King Islanders left their homes built on spindly stilts on the steep, rocky, windswept side of the island, and migrated to the famous coastal town of Nome. They still return to King Island to hunt walrus in the spring. But this past year, the Nome King Islander community did not get a single walrus. That means no walrus meat for the winter — “we’ll have to go to beef,” said long-time hunter Sylvester Ayek (pictured) as he cleaned salmon in his home on a recent morning — fish that normally would be “put up” for the coming winter along with dried walrus meat.

And even more critical than the shortage of nutritious and traditional walrus meat, the failed walrus hunt of last spring means no new ivory tusks, which many King Islanders carve into sculptures, jewelry and trinkets to sell as their main form of income. Native Alaskans are allowed to hunt walrus, bearded seal, whales and other marine mammals in keeping with subsistence rights granted by the federal government. But people will often say “subsistence is an expensive lifestyle” — life has been inexorably altered so that even with subsistence hunting and gathering, heating oil to warm homes in winter and gasoline for boats and snow mobiles are crucial for survival.

And in remote villages and towns in Alaska, energy prices that are wreaking havoc throughout the country are devastating — from $5 all the way to $8 or more for a gallon of gas; and prices of food, clothing and other goods delivered by plane or barge are equally expensive.

Elder King Islanders who spend their days in Nome carving ivory from the community’s spring harvest are now having to buy it at expensive prices on the market, along with getting more frugal and creative in how they use ivory scraps and supplies left over from past years.

“He needs to finish those today and sell them today and then he can go to the grocery store,” said Marilyn Koezuna-Irelan, president of the Nome Native Arts Center, as an elder man carved tiny polar bears with a humming drill in the King Islanders’ center’s carving room. The Nome Native Arts Center, which affiliated with the Alaska Native Arts Foundation, and is slated to actually open in the coming year once full funding and a space is secured, will help carvers cut out the middlemen that take a substantial cut of their profits.

They hope the arts center can help offset what they expect will be continuing lean and unpredictable seal and walrus harvests in the future, due largely to changes in sea ice observed over the past decade. Thinner and more quickly receding sea ice, which are widely attributed to the effects of climate change, mean there is a smaller window in which to hunt walrus, which follow the ice as it recedes north in the spring. Like polar bears, walrus depend on it for their own survival. The shorter possible hunting time means King Islanders must also travel farther on rough seas in small aluminum boats; and are more likely to risk dangerous weather conditions to do so.

On September 15 the Native Arts Foundation’s gallery in New York City will open, giving Native Alaskan artists another venue to get their work out to a wider audience and earn more for it. The gallery will feature work from contemporary Native Alaskan artists rather than artifacts; trying to raise awareness that along with a rich history, Native Alaskans still have a living culture which they are fighting to preserve in the face of forces and changes their ancestors never could have predicted.

Comments