“Bad Credit? No Credit? No Problem! We finance everyone!”

“NO EQUITY REQUIRED. Use cash for bill consolidation, new car, home improvements, vacation.”

“In foreclosure? Call us—we pay ca$h!”

Despite more than a decade of hard work by community and advocacy groups nationwide to stem abusive lending practices, predatory lending continues to plague low- and moderate-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color. Foreclosure rates have spiked nationwide: This year, the number of filings is expected to increase markedly over an already alarming 1.2 million actions filed in 2006.

While there are lots of reasons why homeowners end up in foreclosure, the near-doubling of foreclosure rates in New York City and elsewhere is clearly traceable to abusive products and practices in the high-cost (or “subprime”) mortgage-lending industry. There is broad consensus – now that Wall Street is hurting – that the subprime-lending industry is in crisis, and that public solutions and corporate reforms are urgently needed.

One might get the impression from mainstream media that the subprime-lending industry was doing just fine until companies started to crash, and that borrower fraud coupled with a few rogue brokers have conspired to topple the industry. But for many community and legal-services advocates, it’s as if the rest of the world has finally woken up to the fraud and abuse that have pervaded the subprime industry since it emerged in the 1990s, moving into the vacuum created by decades of bank redlining.

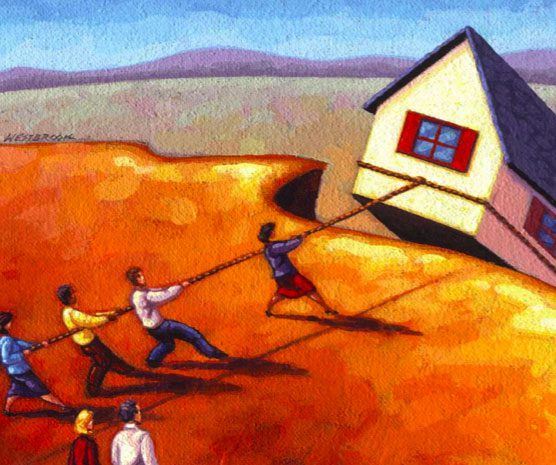

Millions of families nationwide have been devastated by predatory practices, many losing their life’s savings and ending up with ruined credit as a result. Foreclosures stemming from abusive high-cost and exotic mortgages have been overwhelmingly concentrated in neighborhoods of color, not only harming homeowners but also destabilizing entire communities.

On the positive side, the attention from policymakers at all levels of government provides an extraordinary opportunity to address the discriminatory practices that underlie the mortgage market in low- and moderate-income communities and neighborhoods of color throughout the country. Wall Street’s securitization of subprime loans, which continued unabated even after the fraud and deceptive practices of the industry were well-known, fueled the subprime-lending industry’s rapid growth. Now Wall Street must shoulder its responsibility, ensure that borrowers can modify securitized loans, and fundamentally change its standards and processes for securitizing mortgages going forward. It is also crucial that community groups and legal-services advocates, which see first-hand the effects of predatory loans and foreclosures on borrowers and neighborhoods, play a major role in crafting solutions.

The subprime-lending and foreclosure crises present an opportunity-and an obligation-to address fundamental inequities in our credit system. The mortgage market is two-tiered, working differently for people depending on their race and the community in which they live. The damage abusive subprime lending has caused to neighborhoods is profound and will no doubt take many years to undo.

Foreclosures in New York City

In 1999, the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project (NEDAP) began documenting foreclosure filings on one- to four-family homes in New York City, in response to the proliferation of subprime refinancing mortgages in communities of color. New York City experienced quantum increases in foreclosure filings during the past two years. In 2004 and 2005, the numbers were relatively static, with 6,865 and 6,873 foreclosure actions filed, respectively. Last year, however, the number of foreclosure actions filed jumped to 9,089, and this year, taking into account the first 11 weeks of 2007, NEDAP projects 14,730 foreclosure actions will be filed in New York City on one- to four-family homes.

These numbers are alarming on multiple levels. First, the foreclosure numbers were already disturbingly high, corresponding to thousands of families in distress. Second, the filings are overwhelmingly concentrated in a handful of neighborhoods – all communities of color.

Third, the average age of mortgages going into foreclosure has decreased significantly during the past three years. In 2004, the average age of mortgages going into foreclosure was four years. By 2006, the average age had decreased to less than three years. The decrease indicates that many of the loans were unaffordable from the get-go, including many adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs).

Subprime Lending and the Continued Exploitation of Neighborhoods

Since 2000, NEDAP has documented subprime-lending patterns for New York City, showing through maps and data research what studies have demonstrated nationwide: that subprime loans are overwhelmingly concentrated in neighborhoods of color. NEDAP’s segment of a March 2007 report, “Paying More for the American Dream,” documented that blacks in New York City were five times, and Latinos almost four times, more likely to receive a higher-cost home-purchase loan than their white counterparts.

Today, one hears much about newfangled refinancing and home-purchase products, designed for the “savvy investor” but in recent years let loose on the general public. The new array of subprime and exotic products – such as 2/28s and 3/27s, notoriously referred to as “ticking timebombs” and “exploding ARMs,” and interest-only and Option ARMs – are leading to the record-high foreclosures. These include “interest only” mortgages, for which homeowners pay no principal and consequently build zero equity; “stated income” loans, for which borrowers’ incomes are not verified (notwithstanding many borrowers’ ability to document their income); and Option ARMs, which give borrowers the choice of paying principal, or interest only.

Though the current array of subprime and exotic loan products might seem novel, the fundamental issues are in no way new. For years, New York City’s neighborhoods of color have been experiencing successive waves of exploitative lending and real-estate practices.

The first wave consisted of the now-notorious subprime-refinancing scams, which peaked in the late 1990s, as predatory brokers and lenders aggressively targeted lower-income homeowners – especially seniors and women – for high-priced mortgages based on borrowers’ home equity, rather than their ability to repay the loans. Their aim was to “skim equity” from people’s homes in neighborhoods that had long been cut off from access to conventional, mainstream lending. The refinancing abuses led to hundreds of foreclosures in Central Brooklyn and Southeast Queens, among other neighborhoods, and sapped billions of dollars in equity from lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

In 2002, New York State enacted the Responsible Lending Act, modeled largely on the anti-predatory lending law North Carolina had passed three years earlier. The New York law addressed some of the worst refinancing abuses found in the state, but applied only to very high-cost mortgages. The law did not end predatory refinancing practices, but had the salutary effect of lowering the cost of refinancing loans, curbing some of the most egregious gouging.

The next wave of abusive practices emerged soon after the state law passed, with the dramatic increase in property flipping, especially in New York City. Property flipping is typically perpetrated by a group of unscrupulous real-estate speculators, mortgage brokers and lenders, appraisers and inspectors, who operate as a “one-stop shop.” First-time homebuyers are assured that the one-stop shop will take care of all aspects of the home-buying process, from helping them find a house, to obtaining a loan and getting the property appraised and inspected.

What homebuyers do not know is that the homes they are shown were purchased at foreclosure auctions, or otherwise on the cheap. The homes are then fraudulently over-appraised, only cosmetically improved, and quickly sold to unsuspecting first-time homebuyers without a legitimate inspection or loan-brokering process. These buyers end up with a house in need of significant repairs, often with a Section 8 tenant arranged by the property flippers, and with an inflated mortgage. Many quickly default on their loans, end up in foreclosure, and the cycle begins anew.

The refinancing and property-flipping scams have propelled another wave of exploitative practices by a fast-growing sub-industry of “foreclosure bail-out” outfits. Unscrupulous individuals and deed-transfer companies target seniors and lower-income homeowners of color and promise to rescue them from foreclosure by paying off arrears on the outstanding mortgage.

Homeowners sign over the deed to their home to the company and are told they may eventually buy back their home. The “foreclosure rescuer,” however, has no intention of selling the property back to the homeowner. Instead, the homeowner is evicted within months of the transaction and loses every penny of equity she had built up – sometimes in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. New Yorkers for Responsible Lending, a statewide fair-lending coalition of more than 130 organizational members, successfully pressed the New York State legislature to pass a law prohibiting deed theft, which went into effect in February 2007. It is still too early to gauge the law’s impact.

The most recent wave appeared about two years ago, when exotic and unaffordable adjustable-rate mortgage loans began to plague New York City neighborhoods. Edward Jordan is a typical homeowner with an ARM now in foreclosure. A 78-year-old retired post-office worker, Jordan has lived in his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, since 1975. He was induced into refinancing his 6-percent fixed-rate mortgage with a “teaser rate” ARM, which started at 1 percent but jumped to 8 percent in just two months. From the outset, the loan was just a few dollars less than his Social Security income. But when the loan’s interest rate reset, the monthly payments were double his fixed income. According to Meghan Faux, an attorney with the Foreclosure Prevention Project at South Brooklyn Legal Services (SBLS), which is representing Jordan, six seniors with the same loan product have contacted her office in the past few months.

Also common are loans of $500,000 or more made to low- and moderate-income first-time homebuyers. Families with household incomes of $50,000 or less are now routinely receiving these mortgages, which they cannot possibly afford to repay, often on homes that have been fraudulently over-appraised or are in areas where systematic appraisal fraud has driven up comparable housing values. “In the New York market, where housing is so expensive, people are buying houses at fair-market value but don’t have the incomes to support what are unsuitable mortgages,” says Herman De Jesus, a paralegal with SBLS, who has counseled low-income homeowners in foreclosure for the past seven years.

Since the subprime-lending crisis began to affect Wall Street, we have seen a rash of news stories about irresponsible borrowers who get in over their heads with their mortgages. But New York City homeowners in foreclosure tend to tell a very different story about why they took out the mortgages they did: Their loans were made to look affordable.

According to Ann Goldweber, director of St. John’s Law School Elder Law Clinic, with subprime loans, “there’s no semblance of even trying to see if people’s income stream in any way enables them to make payments. Affordability is not taken into consideration.”

Here are just some of the statements borrowers living in New York’s lower-income neighborhoods repeatedly hear from brokers and loan officers seeking to assure them they can afford the loan:

- “Don’t worry about it. You can refinance later.” Prepayment penalties, however, are not mentioned.

- “You can afford this loan if you rent out your basement.” In New York City certificates of occupancy frequently do not allow the addition of a rental unit.

- “See, you can afford this monthly payment.” The homeowner is shown the monthly payment based on interest only, without principal, property taxes, or insurance.

Neighborhood Impacts of Predatory Lending Practices

A trustee of a large New York-based foundation recently commented that predatory lending practices over the past decade have been more harmful to neighborhoods of color than the preceding decades of redlining, when people couldn’t get a mortgage at any price. How destabilizing credit and foreclosures will affect a particular neighborhood depends on local conditions. In New York City, with its high property values, for example, many neighborhoods are generally immune to the blight and abandonment seen in places like Buffalo or Cleveland.

Foreclosures in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick, Brooklyn, have helped fuel gentrification as long-time homeowners – sometimes four or five on a block – are displaced from their homes. Many of the homes are brownstones that homeowners bought 30 or 40 years ago for tens of thousands of dollars, and which now sell for upwards of $1 million. “Houses don’t stay vacant in New York City. Once someone is duped into buying a property and loses the home, it’s just a matter of time getting someone else to buy it, even with property values going down somewhat,” says De Jesus.

Not only are rampant foreclosures helping to accelerate change in the economic and racial make-up of these neighborhoods, but they are also exacerbating the lack of affordable housing in New York City. Foreclosures on two- to four-family and larger multifamily homes have led to wholesale evictions of lower-income tenants. Tenants in multifamily homes suffer as a result of foreclosures when landlords walk away from the home, stop making needed repairs, and fail to communicate with tenants about their housing status. As new owners take over the buildings, particularly in gentrifying neighborhoods, lower-income tenants are driven out to make way for higher rents.

“Sometimes it sounds like we’re bemoaning the marked increase in property values, and we’ve been accused by lenders of trying to downplay the market,” reports Jim Buckley, executive director of University Neighborhood Housing Program. “But it’s out of concern that [brokers and lenders] are making lousy financial assumptions for people in the neighborhoods, based on property values and not on realistic expectations about how willing people are to put a tremendous amount of their income into paying the mortgage, taxes, and so on. And everything assumes that the person’s job situation stays the same.”

“We’ve never seen anything like this,” says Buckley about the spiking foreclosures in the Northwest Bronx, where he has worked for more than 30 years. “On some blocks, it used to be blighted apartment buildings that brought down the value of private homes in the area. Now it’s the private homes that are dragging down conditions on the block.”

What Now?

A coordinated, comprehensive response is needed on the part of community and other nonprofit organizations, government agencies, elected officials, foundations, and the financial-services industry. To date, responses to the subprime-lending and foreclosure crises have been scatter-shot at best.

Mortgage and foreclosure-prevention counseling groups are struggling to meet the increased demand for their services, which are desperately needed at the neighborhood level. (See “Weathering the Storm” in this issue) Even before the current foreclosure wave, however, there were major gaps in the availability and quality of counseling services, a problem that must be acknowledged and addressed to ensure that resources are appropriately scaled up. One national hotline, for example, is touted as a great resource for people facing foreclosure due to traditional reasons, such as loss of job, divorce, or medical emergency. But that hotline, which is funded by financial institutions, does not screen for abusive or discriminatory lending practices. Conceivably, homeowners could be receiving workouts to pay off bad loans that should instead be written down and restructured.

An even greater challenge, perhaps, is figuring out how best to assist the many homeowners with loans on homes that are over-appraised or in areas where real-estate prices have dropped. These homeowners will never recoup their investment by selling their homes. According to De Jesus, “The only way some homeowners can afford to stay in their homes is if we get a write-down of $300,000 or more, which is of course impossible. Their credit is ruined, probably for the rest of their lives.”

The foreclosure crisis requires both remedial and prospective solutions. On the remedial side, we must find ways to assist people in foreclosure and ensure that, wherever practical, financially distressed homeowners can stay in their homes. Loan servicers must make meaningful concessions, by writing down and modifying overpriced, unaffordable loans.

New refinancing products are urgently needed to help people get out of bad mortgages and into sound ones. We will also need to create publicly accountable mechanisms for buying and restructuring non-performing loans that are sold at a discount. Otherwise, bottom-feeding debt buyers will invariably buy up these loans, creating yet another layer of serious problems for borrowers and communities.

On the prospective side, short of overhauling the entire credit system, we can readily ensure that subprime mortgages are made fairly, affordably, and equitably. The New York State Assembly just introduced the 2007 New York State Responsible Lending Act, based on a model bill crafted by New Yorkers for Responsible Lending. The bill requires lenders to verify borrowers’ ability to repay loans, not only when loans are made, but also when the interest rate resets for adjustable-rate mortgages. It requires brokers to act in the borrower’s best interests, essentially codifying a duty that most borrowers believe already exists, and requires subprime and nontraditional lenders to escrow property taxes and insurance. The bill prohibits some of the worst subprime and nontraditional lending abuses, including balloon payments, yield spread premiums, negative amortization, and prepayment penalties, among others.

New York legislators and regulators are pursuing state solutions, notwithstanding federal preemption, which severely impedes states’ ability to enforce fair-lending and other consumer-protection laws against nationally chartered banks. In 2004, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which regulates national banks, ruled that its banks were exempt from state consumer-protection laws, including state anti-predatory lending laws. Within months, New York’s largest banks, HSBC and JPMorgan Chase, gave up their New York State bank charters for national ones, taking advantage of preemption and the OCC’s generally lax enforcement of consumer-protection laws. New York State, however, continues to regulate most mortgage-lending institutions and mortgage brokers. As the country’s financial services center, New York can be a leader in state law reforms, and use its leverage to influence Wall Street and financial institutions.

The four federal banking agencies have a crucial part to play in reforming practices and enforcing existing fair-lending and consumer-protection laws. But to many advocates, the banking regulators have been asleep at the wheel. “Under the pretext of wanting to protect the flow of credit, the federal regulators have abdicated their responsibility to protect the public and have essentially left the industry to its own devices,” says Ruhi Maker, an attorney with the Empire Justice Center in Rochester, N.Y.

The banking agencies have brought only a small handful of public enforcement actions against mortgage-lending institutions in recent years, despite systemic fraud and documented targeting of neighborhoods and borrowers of color. The Federal Reserve Board, for its part, has failed to exercise authority granted to it under the 1994 Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) to prohibit unfair and deceptive mortgage-lending practices. The Fed is now hearing repeated calls from Congress and advocates to use its HOEPA authority.

Wall Street, for its part, must be required to fundamentally change the terms of securitization agreements so that borrowers, who never asked for their loans to be sold in the first place, are not left unable to modify their loans.

Consumer education and disclosures are frequently cited as the solution for protecting borrowers from unsuitable loans and foreclosures – a position that typically reflects the views that legislative, regulatory, and corporate reforms are unnecessary, and that the burden should be on the borrower to make sound choices. But, as Uriah King, policy associate with the Center for Responsible Lending, says: “Education and disclosure are no substitutes for strong laws. Mortgages are complicated transactions, and any closing involves reams and reams of complex information. Even the best-educated borrower can be overwhelmed and misled.” Effective financial education and counseling are both extremely valuable components of prevention and remediation efforts, but are not the solution.

To a large extent, the problems we now face with respect to subprime lending and foreclosures are symptomatic of broader economic injustice in our society. To resolve the crises we need to stop what has been a systematic transfer of wealth from lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color to brokers, lending institutions, and Wall Street.

Comments