It was during 1973 that I first began thinking about a national publication for the housing movement. I was a legal services lawyer helping to build the New Jersey Tenant Organization (NJTO).

It was a time of uncertainty. Richard Nixon had been re-elected by a landslide. By the end of that year, a dozen leading men in the law and order administration were under indictment. The Vice President, stern champion of traditional values, pleaded guilty to corruption, and President Nixon was forced to resign.

The “New Politics” alliance between working class blacks and white middle class activists in the women’s, peace, and environmental movements seemed promising. It was given a boost by the Democratic primaries in 1968 (Kennedy and McCarthy) and revived by Watergate and the success of the McGovern campaign. But I sensed at the time that a coalition that reached no further was doomed to failure. An unassailable majority of Americans were neither black nor radical (or even liberal).

The great political movements of the 60s were waning. But a new populist political movement was growing, one that could add to the middle-class/black alliance.

Harry Boyte was to name this new grassroots movement “The Backyard Revolution.” Socially, these groups valued community stability and cohesion; economically, they fought around bread and butter issues like housing, and targeted corporate interests as their enemy. They sought to deliver government services to urban residents more efficiently and humanely than centralized bureaucrats by relying on the intended beneficiaries to help provide the service; and politically, they sought to democratize and broaden citizen participation in politics.

The tenant movement was very much a part of this activity.

In the 1970s, tenant groups were active all over the country, usually with the aid of legal services lawyers. NJTO was in the midst of winning the most progressive landlord/ tenant laws in the country, including just-cause eviction and rent control in over 40 municipalities. In Boston, thousands of families living in FHA apartments were organizing themselves into the Tenant First Coalition, a dramatic if not typical example of local efforts around the country. (Their story was told in the first and 13th issues of Shelterforce.) Coalitions in many states were forcing legislatures to create laws on issues like leases, condition, and security deposits.

My sense was that a national publication was necessary to link and inform the various local struggles. New Jersey tenant activists provided an excellent recruiting ground for this new endeavor. I first went for help to my brother and close friend Ron, who was also a lawyer and founder of the NJTO. His “can do” attitude gave me confidence that we would succeed. Next, I went to other friends – Pat Morrissy, who was to coin the name Shelterforce, and Phyllis Salowe, the President of the East Orange Tenant Association, and several other organizers and lawyers, including Woody Widrow. We committed our own financial resources and also received a small but helpful financial contribution from the New Jersey chapter of the Lawyers Guild.

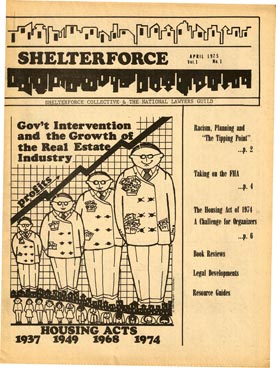

The look and purpose of Shelterforce quickly expanded beyond a lawyers’ publication to include organizers and planners involved in housing. After several tedious months of meeting, gathering mailing lists, and writing and soliciting articles, the first issue was ready for print in April 1975.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, there was no hierarchy. We didn’t even list our full names when identifying who we were. Bylines were shunned. Headlines were decided by committee!

In the first issue, I took the responsibility for writing an article entitled “Who Is SHELTERFORCE?” In it, I wrote: “The SHELTERFORCE Collective is composed of tenant organizers and community workers who live in and around Newark, New Jersey. Some of us also lived and worked in other parts of the country – Boston, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and Detroit. In all these cities we see families forced to live in environments unfit for human habitation, paying exorbitant rents for the privilege of living without benefit of proper heating and water facilities, in cramped, subdivided apartments, in poorly lit, unpainted, deteriorating buildings. In the suburbs, we see people paying unreasonably high rents to live in sterile yet polluted environments, often in apartment buildings whose ‘beauty and charm’ are only a memory of a bygone age.”

The last sentence was personally poignant, since at the time I was organizing my own building in Orange, New Jersey, the beauty and charm of which were fast disappearing before my eyes. (After repeated attempts to force the landlord to make repairs, we went on a rent strike.)

In the article, “Who Is SHELTERFORCE?” I wrote: “As we experience living in a dehumanized society people ask if humanization is even a possibility. People realize that something is seriously wrong in this country but are immobilized by their belief that there are no better alternatives.”

In keeping with the Saul Alinsky community organizing commitment, I declared: “WE THINK THERE ARE THINGS THAT CAN BE DONE. We can have a just society where people do have decent shelter in healthy environments at prices they can well afford.”

“Many people around the country who are active in the struggle for decent housing feel isolated,” I continued “People feel they are struggling alone. In fact, they are not. SHELTERFORCE will be a vehicle for the development of strategies for tenants and housing activists across the country. We will attempt to draw housing movement people together, providing a forum and an impetus for a stronger national movement.”

For the next few years we operated on a volunteer basis out of living rooms, basements, and friends’ offices. Pat Morrissy’s house served as Shelterforce’s home.

Today, a “prosperous” Shelterforce celebrates 20 years with a paid, inspiring staff and a real office.

Comments