This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Dual Crises: Housing in a Changing Climate

The National Clean Investment Fund and the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator program, both part of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, will benefit affordable housing residents and community development organizations.

On Nov. 13, Shelterforce sponsored a webinar on this transformative federal funding for affordable housing. Panelists discussed how individual organizations—including affordable housers—can take advantage of these opportunities and how we can ensure that low-income and disadvantaged communities truly benefit.

Shelterforce’s Lara Heard hosted “The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund: What It Is, How It Will Work, and How Communities Can Truly Benefit,” with panelists

Erica L. King, senior vice president of economic development and lending at the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs

Krista Egger, vice president of building resilient futures at Enterprise Community Partners

Mary Scott Balys, senior vice president of public policy at Opportunity Finance Network

Editor’s note: This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Lara Heard: Shelterforce in the fall did a housing and climate series called Dual Crises: Housing in a Changing Climate. We covered a range of topics about the climate crisis and housing crossover, which includes things like extreme heat, what makes affordable housing green, folks who are relocating communities away from the coasts in response to climate change, our response to wildfires, and a lot more.

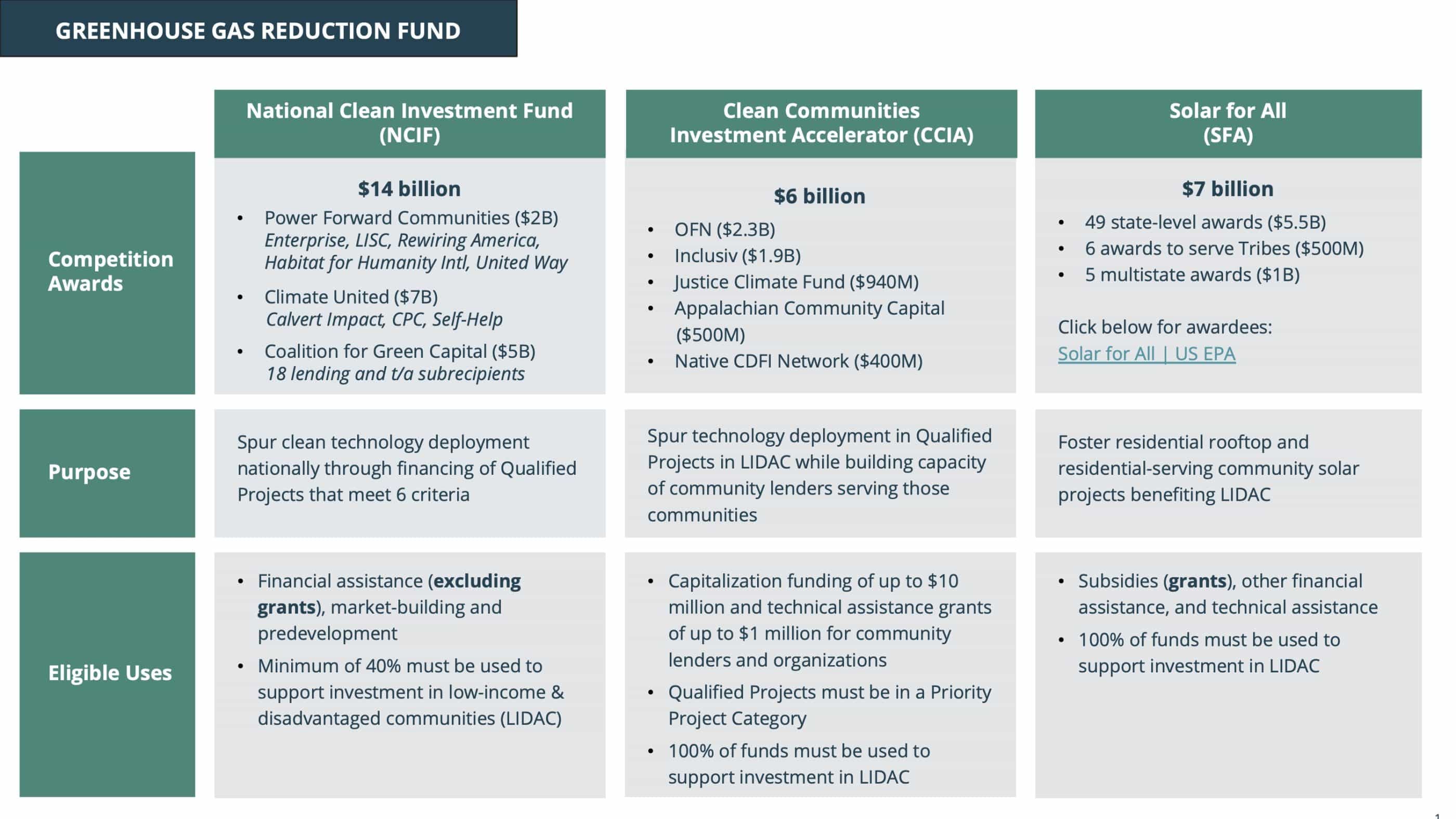

One of the things that we covered was the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), which is a $27 billion fund. To give a little context for those who don’t know about it, it was created in 2022 by the Inflation Reduction Act. But the funds were officially awarded in April and obligated in August.

And the goals of those funds are green investment in communities that need it: Reducing air pollution, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and overall mobilizing private capital for the climate crisis. Something really important and unique about them is that a significant portion of the funds are required to benefit low income and disadvantaged communities, which is one of the reasons that Shelterforce was interested in it.

The three funds are: the $14 billion National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF), given to three different groups; the $6 billion Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA), distributed across five different groups, which will in turn distribute the funds further; and the $7 billion Solar for All program, which goes to 60 recipients.

Panelists, would you introduce yourselves and tell us what organizations you represent and how you’re related to the funds?

KRISTA EGGER: I work for Enterprise Community Partners, which is a national nonprofit in the affordable housing space.

And as part of a coalition with four other amazing groups—including LISC, Rewiring America, Habitat for Humanity International, and United Way Worldwide—we are part of the Power Forward Communities coalition, which is one of the NCIF awardees within the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. And today I’ll be sharing more about Enterprise’s role in Power Forward, really more on the multifamily housing side of things.

ERICA KING: I am the senior vice president of economic development and lending for the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs. Our organization is a coalition of Black-led community development financial institutions, otherwise known as CDFIs, all with a common theme.

All of our institutions, as well as our organization, are committed to closing the racial wealth gap by identifying opportunities that result in economic opportunities for the organizations that our CEOs lead, as well as the communities they serve.

Our role within GGRF is that we are a part of the Justice Climate Fund’s Clean Communities Investment Accelerator application. We’re serving as a trade coordinator to help recruit community lenders to the program. I’ll be talking a little bit more about our approach to the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator program, as well as how community lenders can benefit.

MARY SCOTT BALYS: I’m with Opportunity Finance Network. OFN is an association of over 470 mission-driven community lenders—primarily CDFIs, but not exclusively—working in every state across the country, as well as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the District of Columbia to bring access to capital to disadvantaged communities. Our members were already doing housing work, already doing small business, community facilities, and a little over half of them prior to GGRF were already doing climate or energy efficiency-related work. OFN is a CDFI ourselves also. We’re certified by Department of Treasury, and we provide intermediary lending to our members. So under GGRF, we are a recipient under CCIA as well.

We’ll be managing just under $2.3 billion to distribute to our members to support their capacity building and development and market building around energy efficiency and climate lending.

The CCIA and NCIF work a little differently than the Solar for All program, which has 60 recipients, which include tribes, states, and nonprofits. It’s specifically aimed for residential solar for low income and disadvantaged communities.

We’re going to be focusing more on CCIA and NCIF. The National Clean Investment Fund and Clean Communities Investment Accelerator seem pretty similar on the surface. How do we tell them apart and what should we know about them?

KING: When we look at those two particular applications or competitions, the National Clean Investment Fund is a $14 billion pool that was awarded to three national hubs. And the objective of this particular program is to support clean technology projects across the country by delivering accessible affordable financing.

One of the key differences is the funding flow and the funding type. For NCIF, this program offers primarily low-cost loans to private sector investors, developers, community organizations, and other groups to help deploy projects and mobilize private capital at scale.

So think of NCIF as project-based funding. Another distinction is that at least 40 percent of the capital provided under the program must benefit low income and disadvantaged communities.

When we talk about the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator, or CCIA for short, this is a $6 billion pool of funding that was awarded to five national hubs, ourselves included, the Justice Climate Fund, as well as OFN, that you heard earlier.

The objective of the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator is to provide funding and technical assistance directly to community lenders in low income and disadvantaged communities. And this helps provide these intermediaries with pathways to deploy projects in communities that need it most, that are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, while also helping to build the capacity of these community lenders so that they’re able to continue to finance projects of these types in perpetuity.

The way that the funding flows under the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator is that the national awardees will provide capitalization funding to community lenders … up to $10 million per community lender. In addition to the capitalization funding, they’re also able to provide development and technical assistance funding up to $1 million to that community lender.

In addition, they’ll be providing education and training to help those lenders build their capacity to deploy distributed energy and other clean technology resources that help to achieve net zero buildings, or to achieve zero emissions, and transportation and other projects where it’s needed the most.

What makes this application different from NCIF is that 100 percent of the funding must benefit low income and disadvantaged communities. So think of NCIF as project-based to support projects directly, and then CCIA is supporting community lenders with the capital who will then support projects and community.

EGGER: Many of the things that Erica shared in terms of NCIF are direct project funding. CCIA you could consider almost as intermediary funding to support market-building activities and then Solar for All separate from the states, tribes, and coalitions of nonprofits that are deploying that funding.

For NCIF, at least 40 percent of this funding must be used to support residents in low-income and disadvantaged communities, [which is the] LIDAC term that EPA uses throughout GGRF.

That aligns with the Biden administration’s Justice 40 commitments, while with CCIA, 100 percent of the funds must be used in LIDAC communities. Both of the initiatives certainly are supporting affordable communities, but doing it in slightly different ways. And of course, all of the awarded coalitions are putting their own spin on this as well.

And as I mentioned earlier, Enterprise is part of Power Forward Communities, and a unique aspect that we’re taking there is really focusing our entire award on the residential sector, specifically affordable housing, both multifamily and single family, as well as new construction and retrofits.

Climate United and Coalition for Green Capital, the other two NCIF-awarded coalitions, have broader focus areas than just housing. There is no restriction on using multiple sources of GGRF funding in a single project, so a singular project may end up receiving NCIF, CCIA, and Solar for All funding, if the scope of work matches those requirements. So these can be mixed and matched to some regard, as long as eligibility guidelines are met.

All three of you represent organizations that have been either awarded funds or are part of coalitions that were awarded funds. What should folks know about your timeline for distribution and how the rollout is going?

BALYS: Like you mentioned earlier, Lara, the funds were just awarded officially in August, and it takes some time to iron out all of the terms and conditions and things like that. So you’ve probably been hearing about GGRF for more than two years now, but funds are just beginning to start to flow.

From OFN’s perspective, I can talk a little about our timeline specifically. We opened a pilot round of applications for funding for our members about a month ago. And for that round, we are specifically looking to do a smaller cohort of awardees, probably around 10 or 15. And we are concentrating on OFN members in good standing who have participated in our pipeline request when we were putting our application together and have some experience working on climate or energy efficiency related projects.

We’re looking to use this small group as a pilot round, to help both OFN learn how to administer the program, how to comply with all of EPA’s existing reporting requirements and other pieces, and how to set up our own transparency and community engagement and other pieces that we want in place from our perspective and work with our members to really learn from them what they need to be able to use this brand new program.

So we have that application period for that pilot round. We are anticipating making those awards [in] early 2025 and then opening subsequent rounds. We are likely to do multiple rounds every year over the six-year life of the program. I can talk a little bit more later on about how we’re approaching that and different categories we’re using and things like that, but there will be multiple rounds. Nobody is late to the game at this point. I think every organization is just starting to get going. We are going to do a full round sometime in Q1 of next year. And then in conjunction with that, we are also launching a nascent climate lender training program early next year as well, which I can talk about a little bit more later.

I think a brand new program for EPA to set up, a brand new program for each of the grantees to administer and to our members, these things take a little time and we want to be sure that we are doing this right by EPA’s requirements and with congressional oversight and things like that, but also doing right by our members and the communities they serve.

EGGER: The same principles about timeline that Mary Scott shared for OFN apply to Power Forward Communities as well. We’re in the stage of operationalizing our program design so we can … secure technical assistance providers that can help in our market-building work.

And we’re finalizing our term sheets for our capital product. We will have financial assistance via loans as well as pre-development grants available. And the intake forms for accessing those will go live in first quarter in January. We’re working through all of the details now to ensure that when we officially launch, there won’t be any information that we have to correct or roll back.

But it’ll be full steam ahead. So y’all can look forward to updates for the Power Forward Communities website in January to include both the intake form for evaluating properties and portfolios for potential financial assistance, as well as for more information about where our market-building activities will be launching first.

If you go to the Power Forward Communities website today, you can sign up to be on the email list so you get a notification as soon as our work is updated. And similar to what Mary Scott shared, we are not setting up a program to just be first-come, first-serve. We know that there are many valuable projects to engage with that won’t necessarily be ready right out of the gate. And that’s what we’re really looking forward to leaning into, the impact of Power Forward Communities in terms of assisting projects and organizations that need the extra time and assistance to be able to engage in this decarbonization work.

We’ll have certain tranches of funding and technical assistance open and available throughout the seven-year period of performance, if not longer than seven years. So we’re hopeful that this will be a long-term program for us.

Erica, did you want to talk a little bit about Justice Climate Fund?

KING: My response is also going to be very similar to that of Mary Scott and Krista, that we’re being very thoughtful, taking our time to ensure that all the right people are in place. The Justice Climate Fund is a newer nonprofit organization that organized around GGRF, and so we’re building out the team. Justice Climate Fund plans to open its application sometime during the first quarter of 2025. But keep in mind that the program funds community lenders who will then fund community projects. So funds will reach those lenders at some point in 2025, but it’s likely that we won’t begin to see an infiltration of capital into community until about Q3 2025.

And so for those folks that are representing community organizations or may have projects, I would say it’s also important to research the CDFIs that may be near you. You can do this by going to the CDFI Fund and you can simply search your area and it will populate a list of all the CDFIs that are near you.

But in addition to that, I would also advise folks to follow the Justice Climate Fund’s application so that you can receive announcements and news so that you can also be abreast of when the application opens. And if there’s publication about lenders that are receiving that funding as well, that will be the best place to go for that information.

So it’s in process. The applications we hope to open soon within the next quarter, and we’re excited about that and more to come. One thing Krista just mentioned is that NCIF is a seven-year program. I also want to highlight that CCIA is a six-year program. So there is time. Justice Climate Fund also plans to introduce funding in waves so that it allows opportunity for lenders at whatever stage they are to get prepared for the funding ahead.

How can we make sure these funds are distributed fairly across the organizations and the subgrantees that they will be given out to? How do we keep smaller organizations from missing out?

BALYS: We’re very intentional about this with our 470 members. I should say, our funding is going to be available to OFN members. Those are primarily CDFIs, but not exclusively CDFIs.

If you go to our website under membership, you can look at the criteria. If you are a mission-driven community lender you could potentially meet the requirements to become a member … It’s not only going to people who are currently members, you can continue to apply beyond today.

But we’re very focused on ensuring our smaller members have access to it. This has been, pre-GGRF, a focus of our organization over the past several years to get more of our funding and our programs to touch smaller CDFIs and to help them where they are.

With GGRF specifically, there’s two different ways that I want to talk about how we’re doing this that I haven’t touched on already. The first is for our funding and participating in general, we have established four different categories for lenders: starting at nascent and then emerging, maturing, and established climate lenders.

And we want to be able to do this to meet all of our members where they are. Like I talked about at the beginning, we have … several members that have been doing energy efficiency and climate work for a decade or more and know exactly what they’re doing, have a pipeline of projects ready to go, just need the help and the funding and can get right to work. We have other members who have never touched anything related to this, or are interested in it, but have never underwritten a project with solar panels on it or anything else. And in between there. We want to be able to meet each of those members where they are and then be able to provide them what they need at that point. So if you come in as a nascent climate lender, you’re not eligible right off the bat to receive grant funding. You’re eligible to go into our nascent climate lender training. And you have to go through that training before you’re eligible to take grant dollars on…

And then those other three levels, as you go through, you can come back in these subsequent rounds. And get some grant dollars on your balance sheet or some technical assistance funding, go work through some projects in a cohort, be able to move up, and maybe a year or two later, you’re able to come back and get more grant financing. We are also working to connect our members to the NCIF awardees—like Krista was saying, you can use from multiple different pots.

And we have some members who are either part of coalitions or themselves are going to be administering Solar for All dollars. So when a state government either declined to apply directly or there’s some multi-state coalitions, our members are touching all of these places. The biggest thing is we want to meet people where they are and ensure that as they continue to grow their capacity in climate lending, they can come back and receive more resources.

The second piece is related to the nascent climate lender training. Say you’re a very small CDFI. Maybe you have two or three employees. Asking them to give up their time to go through this long training program could be a challenge and could be a barrier that prevents them from accessing the program. So we are planning to issue stipends on a sliding scale based on number of FTEs in an organization, to help offset the employee time that is spent in the training. We think that’s vitally important. We know when our members are looking at what they can get done, they want to be able to do the work, and it’s sometimes difficult to make those choices to go into training to then be able to offer these climate programs.

And sometimes those climate and energy efficiency features are the first things that are eliminated from a project due to cost. So as much as possible, we would like to be able to mitigate that and to give everyone opportunity and access to the funds.

EGGER: We’re looking forward to being able to support organizations of all sizes, but in particular the owners and operators of small and medium-sized multifamily properties are what Enterprise and LISC will be looking at because those aspects of the market are often hardest to serve and we’ll be looking to see if we can prioritize those through this funding opportunity. In general, taking a step back, just looking at the approach of our coalition, Power Forward Communities, we have allocated a significant amount of our award to market-building activities.

Some examples of these market-building activities that are designed to really boost the market so that all owners, but particularly those that don’t have dedicated resources for this on staff, are better able to participate in this energy transition include looking at aggregating demand across technologies that are efficient and electric, such as heat pumps, to be able to lower the actual purchase price of these systems for households.

We’ll be developing online planning tools, building off of some of the great work that our coalition member Rewiring America has already created for the single-family market. These online planning tools will be able to cover and reveal what incentives—apart from and in addition to GGRF funding—are available for projects, to be a part of the capital stack. They’ll also identify estimated bill savings folks can expect from implementing certain scopes of work. These online planning tools should help speed up and make more transparent the decision-making process for organizations who are engaging.

We’re also planning a consumer activation campaign in partnership with the United Way and their 211 help desks. Throughout the country, we’re planning a program to engage community leaders and community-based navigators for this, along with direct technical assistance that we’ll be able to provide in terms of capacity building. More so for the multifamily side of the market, as well as a workforce development approach that LISC within our coalition is leading.

All these market-building activities are designed to make it easier for anyone and everyone, but perhaps the smaller organizations in particular, to engage. And that’s in addition to the financial assistance that we’ll have available both on the single family and the multifamily side. This technical assistance and outreach and support of community-based organizations is a high priority of ours.

Otherwise, I think what I mentioned before about phasing out deployment of the capital is also important for smaller organizations to keep in mind. And if you are representing a smaller organization today and you’re on this call and you’re thinking about what you can do to get ready, to really position [yourself] to be eligible to access GGRF funding or in particular NCIF funding, I think some of the things that you can already do [to] start phasing in this work over time so it’s less of a burden [later] is start prioritizing which properties within your portfolios are the best candidates for moving to zero emissions. This might be based on how much energy usage they have today, what the utility bill profile looks for those properties, which properties are intending to engage in recapitalization events sooner than later, and how you could build in or blend in decarbonization activities into those, etc.

You might also be a smaller organization that’s in an area of the country that has local or state mandates or incentives for reducing emissions associated with your properties, and if that’s the case you can think about these sources of capital as a way to help pay for that compliance. So look at how the requirements and incentives of your local programs may compare to these national and federal initiatives to help you achieve two goals at once.

We’re really viewing our job—in terms of Enterprise’s role within PFC—as assisting the multifamily affordable housing sector in particular to be eligible for these funds.

And I think your question, Lara, about how we can ensure that the funds are distributed fairly is something that we’ve tried to bake into our program design, but certainly will be reevaluating and iterating on as time goes on to make sure that we’re successful with that.

I wanted to go to Erica to talk about Justice Climate Fund also.

KING: Just a reminder, the final application and the eligibility criteria has not yet been released. But I can say that the Justice Climate Fund is being very thoughtful as to the planning and execution to ensure that smaller CDFIs aren’t excluded from funding and that they have a path towards accessing this capital.

And just to reiterate, the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator is all about building the capacity of lenders to be able to provide more green lending solutions or develop solutions that they weren’t already doing.

Our organization at the Alliance, we’ve been working for the past couple of years to ensure that our members are prepared for green lending activity. We do that through providing clean energy certification programs or giving them access to those cohorts where they can get clean energy certification programs. We ourselves have provided workshops and webinars around clean energy tech, incentives, rebates, so that our members can get an understanding of what the ecosystem looks like, hoping to provide partnership opportunities, loan participation opportunities, to help shorten the learning curve.

All of these things we’ve been doing over the past couple of years have been to help build the capacity of those smaller CDFIs so that they can participate in the opportunity, and the Justice Climate Fund will continue to do this work through its CCIA program.

One of the things that the Justice Climate Fund plans to do—and again, final criteria and eligibility have not yet been released—there will be an assessment of all applicants to determine their readiness, their ability to participate in training and development that the program is set to provide.

There’s going to be customized training that every lender will be required to go through. And also depending on their level of understanding and readiness to deploy clean energy capital, that training will look different, right? It’s very much built with intentionality to meet members where they are. And because of the program’s components, being a six-year program, we want to make sure, of course, that funding does not run out during that six years and some of the larger CDFIs aren’t just the first in the wave to receive funding.

And so there will be some sort of reservation of capital upon application acceptance. We’ll spell that out a little bit more in detail, but some of those things are being built in to ensure that funds aren’t exhausted by the time the smaller CDFIs that may not have the experience in offering products, go through training, go through programming, get their questions answered.

They’re being very intentional about ensuring that there is a trajectory and there’s a path for smaller CDFIs to be able to be a player in this space.

Is there any concern about the change of administration affecting the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and its rollout? Are the funds in peril?

BALYS: Specifically regarding the funding, since it has been obligated and the funding has been disbursed to a fiscal agent, it cannot be clawed back without cause. Obviously if an organization were to violate the terms and conditions of the agreement or some other fraud or abuse or something like that, money could be clawed back by the federal government, but it could not just be rescinded by the administration, by Congress, or in any of those typical ways that money can be pulled back after it’s been allocated.

There are other parts of the Inflation Reduction Act that I think are potentially more at risk or some of the tax incentives that may not be continued or things like that. But GGRF specifically, I think the funding is legally obligated and cannot just be rescinded.

There could be challenges depending on how EPA decides to administer the program moving forward. But again, we have our terms and conditions and we all signed our contracts. So everything by both the federal government side and the awardees has to be in line with those legal documents.

EGGER: I’ll just add that our funding is under the same parameters as Mary Scott just described for OFN and CCIA. We signed a seven-year contract with EPA in August, and we are really excited to fulfill the responsibilities within that contract. We understand that regardless of administration, Americans need efficient solutions to preserve affordable housing, lower energy bills, create good-paying jobs. We’re hoping that we’ll be able to deliver those types of results expediently with this program.

BALYS: I’ll just add, yes, it was a bill that passed under a reconciliation bill with no Republican support, but there are some concepts of reducing energy burden for homeowners or for small businesses or others that I do believe will have universal support. So I think at this point, yes, we are excited to administer the funds. We are also very concentrated on transparency and accountability and making sure the funds make an impact for Americans and we believe that that will help gain support regardless of political affiliation or where you are in the country.

I’m really glad we answered that because it’s an important question and on everyone’s minds.

So going back to these funds, a lot of them are earmarked for low-income and disadvantaged communities, which is defined as a combo of communities with certain environmental and socioeconomic challenges, along with low-income folks. How can we make sure they really achieve that and that they do what they’re supposed to for these communities that really need them?

KING: The benefits are kind of fundamentally built into CCIA, because 100 percent of the funding has to benefit low income and disadvantaged communities. It says that on paper. How do we ensure that in a practical way? I think it’s all about empowering communities and those institutions that are within those communities to serve them. We want to ensure that we’re educating the community on the benefits of clean energy technology. Also, we want to educate on the opportunity cost of doing nothing. What does that mean for being excluded from this market? What does this mean for everyone else that may have transitioned? What does it mean in terms of what the energy burden might be for those that are still left on the grid or are still left using dirty energy?

And so we really need to uplift that in community, so that there’s buy-in. It’s one thing to come into a community to say this is what you need and why, versus showing and demonstrating and explaining. So perhaps having community centers be a model for the benefits of clean technology. And I think that it’s going to take community organizations to uplift that. There is a lot of infrastructure building that needs to occur in community to ensure that they are really benefiting from GGRF. The incentives are great that IRA presents. GGRF in itself, being able to have access to low-cost capital. But if the infrastructure isn’t built in such a way that can receive new technology, then we’re doing ourselves a disservice, and we’re not necessarily positioning communities to be able to truly benefit from the opportunity.

We need to think about what infrastructure needs to be put in place in order to make ready for the new technology. And many low income and disadvantaged communities have a lot of work. Are we looking at policies? Are we looking at additional funding and other opportunities that help to build up that infrastructure so that GGRF can really do what it intends to do? We also want to ensure that there’s workforce within community to be able to support those projects. If we think of GGRF as just a funding opportunity—and I am quoting Amir, the [CEO] of Justice Climate Fund, who had a really captivating comment—if we look at GGRF as just providing funding, we’re truly missing the essence of impact that the program can potentially have.

There’s workforce opportunity impact. And if we don’t allow that to be developed within community then we’re missing out on that opportunity. There’s new markets for community to be able to take advantage of. And if we’re not looking at ways in which we can address that and help to build those new market opportunities, create a new set of small businesses within those communities—[for example,] that can be an installer or that can be a vendor of some of the clean technology products—then we’re missing out on that opportunity as well.

If we focus on the entire ecosystem and building that up, then we can truly ensure that low income and disadvantaged communities benefit from GGRF. As well as IRA.

Krista, did you want to talk a little bit about the distinction between CCIA and NCIA?

EGGER: The question about how these funds can benefit low income and disadvantaged communities as defined by EPA is part of the reason that Enterprise and all of our coalition members signed up to create Power Forward Communities. This is the demographic that our organization serve day in and day out and have for decades.

We mentioned earlier that 100 percent of the CCIA funds must go towards LIDAC [low-income and disadvantaged communities] communities as well. At least 40 percent of the NCIF funds must. Within our coalition’s approach, Power Forward Communities is committed to ensuring that at least 75 percent of all of our funding will be benefiting LIDAC communities, so nearly doubling that required commitment and we’re hoping that that we’ll exceed that.

In a sense, it’s baked into this funding to have that kind of impact. I will say that in our designing our programmatic approach, both in terms of technical assistance as well as the financial assistance, we are trying to keep a keen eye towards avoiding any unintended negative consequences of deploying the funding. So for instance, we know that in certain parts of the country today, if you simply swap out a gas appliance for an electric one, depending on what electric rates look like, that will determine how your utility bills are at the end of the day. Could be higher, could be lower. We are not going to take a haphazard approach to that. We’re going to take an intentional approach to ensuring that we’re managing energy burdens throughout this work so that there aren’t any inadvertent consequences in terms of higher bills when they could be managed with bigger investments in energy efficiency, for instance, in a property, in addition to the electrification and the clean energy work.

Pairing those together—energy efficiency, electrification, and clean power—is really a strategy that we’re leaning into heavily to ensure that families will benefit with lower bills at the end of the day. And if you couple that with the addition of electric vehicles, you can see even greater savings so this is certainly one of the aspects that we’re looking forward to being able to pursue.

BALYS: What Erica and Krista talked about are also things that we are looking at, but I want to highlight a couple other things. Krista mentioned that the LIDAC focus is baked into these programs. I think it’s also baked into all of our organizations and mission-driven lenders, all of our members. If you’re a CDFI, it’s a part of your certification through Treasury that you have to have accountability to your target market and your community, and that includes representation.

But I also think with CCIA in particular, it’s even more baked in by the model where yes, as a national organization, we initially received the funds, but 90 percent of that funding is flowing back out to our members and those will be those on-the-ground community-based organizations. You have CDFIs that are able to know what their community needs. What does your energy market, your electrical rates look like? What are the best resources for decarbonization there? I think the distributed model itself helps to drive community outreach and engagement.

We are requiring all of our applicants for funding to have an outreach and engagement plan for the community to make sure that they’re doing that, it’s not just OFN doing outreach or putting out information, that the individual organizations are doing it.

Erica talked about workforce training, and I think this is a huge place where we can make sure that the benefits are really flowing into a LIDAC community. All of these projects require contractors, installers, maintenance afterwards, a variety of positions, and we are also subject to Davis-Bacon and related acts, which means they have to be paying a prevailing wage. I think it is vitally important to make sure if you’re sending this money into a community and you’re going to be paying a prevailing wage, we should do everything possible to ensure those businesses and employees are also from the community.

Some of our members not related to GGRF funding, just the work that they’re already doing, are looking to build both this energy efficiency and small business ecosystem. I’ll use one example. One of our members located in Maine, Coastal Enterprises, or CEI, they have been looking at energy efficiency and with a lot of these programs, the first thing you need is a home energy audit to be able to see where the gaps are, or for some of the tax incentives, you have to prove a certain improvement in efficiency. But there aren’t enough people trained to do that. So they are partnering with an organization that’s providing that training to get individuals the resources they need to set up their home energy efficiency audit programs.

And then when those individuals complete the training, CEI is able to provide them some working capital loans in order to get their business started. And then they also have a list of contractors who they know have been trained properly, whose business plans they’ve looked at so that they know that those are going to be sustainable businesses that are around for the next several years that they can work with when they do want to go into a project and need to find someone.

That’s one small example. Some of our members are looking at different ways of doing that work across the country, but I think those are the kind of models that we as the national entity are going to want to elevate and allow our members to be aware of them, to facilitate peer learning to see what would work in their community. From our seat, we’re not necessarily going to be able to provide on the ground training to different elements of the workforce, but making those connections between technical colleges, community colleges, other training opportunities, and to be able to support those small businesses that are going to power a green economy and be able to maintain those solar panels 15 years down the road or 20 years down the road, or that electric vehicle, I think that’s an important piece of this as well.

Our final question before we move into the Q&A: These funds touch on a number of areas of the climate crisis. They cross over many different projects, many different communities. They’re super ambitious. So for those here who have a housing interest, what’s in the fund for affordable housing?

EGGER: Power Forward Communities is all in on affordable housing, and Enterprise, LISC, Habitat for Humanity international, that’s our bread and butter day in and day out. In partnership with Rewiring [America] and United Way, our organizations touch about 99 percent of the counties throughout the United States, primarily working in communities of affordable housing.

GGRF is a historic climate investment, but we’re really trying to view it as a historic investment in affordable housing and how it can be leveraged to preserve and produce more efficient, healthy, resilient high-quality affordable housing.

As you can imagine, with the name Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the primary goal of the funding is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with different projects. While building, transportation, and clean power can be eligible uses of the funding, our Power Forward Communities Coalition is focusing on the affordable housing component.

And one thing that I really appreciate about how NCIF was designed is that the funding can go towards elements that reduce emissions in a building. For instance, adding roof insulation or installing more efficient heat pumps, water heaters, stoves, windows and doors, etc.

But what I especially appreciate is that it can be also pay for enabling upgrades that are necessary to make those things happen. There is a lot of deferred maintenance across the affordable housing stock, so with these funds, if, for instance, you’re needing to open a wall throughout a renovation to install more insulation and you discover that there are health and safety measures that need to be abated, repair of those could be considered an enabling measure and a use of these funds to upgrade the home in that way. Similarly, if you are switching from one fuel type that’s not electric to an electric source, funds are eligible to be used for upgrading the electric service to your property, which we know is such a large expense and often a barrier for affordable housers to do that type of work, but it can be covered here.

I’m really excited not only about the opportunity to reduce emissions through this fund, but to improve the health and safety and resilience and address some of those deferred maintenance issues as they relate to upgrades in housing, that will meet the climate goals. I’m really looking forward to how this can come to fruition.

KING: The members that the Alliance represent all work in various sectors of lending. We do have those that are focused in affordable housing, whether it be development or expansion. We have those lenders that are focused on small business lending and other community facilities development. And so who we serve runs the gamut.

Now, when you look at Justice Climate Fund’s application, it represents not just CDFIs, but also CDFI banks as well as CDFI loan funds and other green banks. And as a collective, we do realize that housing is an important component and it plays a huge role in the emission of carbon. If we don’t look at and address how GGRF can support helping those homes or buildings become clean we’re missing out on a huge opportunity.

Now, when we talk about affordable housing, we know it’s pretty tough in certain communities to do affordable housing development projects. There’s other financial tools that can be used like LIHTC and others that help bridge a gap to make those projects more feasible.

We see GGRF as another opportunity, another tool in a toolbox, to be able to identify ways in which we can ensure that affordable housing projects can increase.

And we can bridge the gap through maybe some of the incentives offered through GGRF’s low cost capital component, whether it’s NCIF, whether it’s CCIA, but also other incentives like rebates and tax credits that may be offered through IRA that can help further bridge that gap and make the affordable housing projects more feasible in low income and disadvantaged communities.

And so time will tell, but there’s clearly opportunities for GGRF to play a role in this space of affordable housing.

BALYS: I’ll talk a little bit about OFN’s work around housing. Similar to what Erica just said, our members represent housing lenders, small business lenders, nonprofit lenders, agriculture lenders, a little bit of everything. A lot of them do multiple things at once but somewhere between 30 and 40 percent of our members are primarily housing lenders. So that is obviously going to be a huge focus of the work that our members are doing with CCIA funding. Krista also referenced some of the eligible project categories. There’s some difference, but under CCIA specifically every project has to fit in one of three large categories: Distributed energy generation or storage—things like solar panels and battery storage. The second one is net zero emission buildings. And then the third is zero emission transportation.

And I think housing fits. Probably the most straightforward way to think of housing is for both distributed energy generation or storage and for net zero emission buildings. Those are natural fits for housing.

We know it’s going to be a challenge, particularly with retrofitting toward net zero emission buildings. But that is something that we have spent a lot of time thinking about. It does not have to be one shot, you immediately get a building [that] hasn’t had any upgrades in 50 years to net zero emissions in one project. You just have to have a plan and show significant progress toward reaching that goal. So we are definitely focused on how to approach that in addition to new construction.

I think residential installation of solar panels is going to be an obvious one under both Solar for All and all the other programs. We have members that are working on multifamily housing, members that do single family homeownership, all pieces of the housing market. Those are going to be a huge component of our program and we think, as you’re looking at your portfolio, it’s likely going to be housing that is the first thing to pop to your mind. I think there are a lot of small business cases that maybe aren’t quite as obvious. But I think those are going to be some of the first projects we see out the gate.

Moving to audience Q&A: Are all of the NCIF funds going to multifamily projects? Or is that specifically what Power Forward Communities is focusing on? And are there other NCIF funds that will be focused on single-family units?

EGGER: Single family is certainly an eligible category for NCIF as long as all of the fine print is met. Power Forward Communities will be focusing on single family as well as multifamily, new construction as well as retrofits. Enterprise’s role is primarily multifamily. And so that’s probably why that is coming through stronger from what I’ve shared so far. Certainly all those classes of housing are relevant here.

This isn’t specific to NCIF, but does any of the funding include organizations that are interested in forming CDFIs for green lending activity or technical assistance?

BALYS: First, none of the GGRF funding would necessarily be available to help you become a CDFI, but you do not have to already be a CDFI in order to access the funding. For our membership, you don’t have to already be a certified CDFI. We have members who are in the process of pursuing their certification, or are not interested in doing that, that will be eligible for funding. So it’s not an exclusionary piece.

There is technical assistance funding available under GGRF, but is related to those projects and specifically climate lending capacity, not to going through the process to get your certification. Yes, you’re eligible. No, it would not help you become a CDFI necessarily.

KING: Yeah, per EPA requirements or guidelines, CDFIsare eligible, but also nonprofit loan funds are eligible. Now, depending on the awardee’s criteria that they’ve put forth in terms of who each hub is interested in funding, that will vary. But there is a path for nonprofit loan funds to be able to receive some GGRF funding.

Our organization has programming that exist for a category of members. We have associate members that are not yet fully certified CDFIs, but are on a path towards becoming that. And we offer programming to help those organizations become CDFIs. Again, our membership, you know, Black-led CDFIs, CEOs of CDFIs. And so that’s self-identified. So if that fits you, we’re happy to have conversations with you about becoming an associate member. That will allow you access to some of the programming that we have to help you become the CDFI if you want to.

BALYS: OFN also has affiliate member or ally memberships and a lot of our training programs are not exclusive to our members. So some of that is like a CDFI 101 program. We have a climate lending 101 program. And then others around underwriting, capital staff building, etc. So those programs that might be useful are not exclusive to our members.

This question is mostly for Krista, but relevant for all. Are you thinking about requiring or incentivizing tenant protections for projects under your fund?

EGGER: That’s a great question, and we certainly are interested in ensuring long-term affordability with all the projects that receive investment. We’ll be taking the approach of when we enter into a community with our market-building activities, we’ll be engaging with community members to really guide what type of benefits to associate with our market-building and our financial assistance in those areas. Certainly, with the projects that we may be investing in that receive other subsidies for affordable housing, we’re expecting there to be longer term covenants protecting affordability. But as our funding may also be used in unsubsidized affordable housing, we’ll be looking to determine what tenant protections or community benefits are appropriate for that specific location. We’ll have more information about that when we launch in January.

BALYS: I can’t speak to specific project requirements since CCIA is not direct project funding, but I know it’s part of EPA’s application process. Every applicant and now awardee had to consider consumer protection, housing affordability protection, and come up with a plan for those. So it should be a focus of every awardee moving forward.

Is there an opportunity for mobile home communities to access the funding to upgrade substandard electrical infrastructure so that parks can accommodate net zero manufactured home models?

EGGER: I think mobile homes are just as eligible as any other home type as long as they’re meeting the fine print and the requirements of the funding. As I was mentioning earlier, while there’s a focus within NCIF, at least, on meeting certain emissions reduction thresholds, enabling measures to achieve those may also be eligible to be covered with the funding. So upgrading electric service and electric infrastructure if it is reasonable and necessary to achieve emissions reduction in the particular home renovation, could be an eligible use.

The bottom line is there’s nothing excluding mobile homes from accessing the funding, and I encourage you to look at how the different NCIF programs could be a good fit for what you’re doing.

Do you know of any threats to CDFIs under the new administration?

KING: You know, the CDFI as an industry has many benefits that serve lots of different geographic areas, right? Not just red, but blue as well. And so I think it’s important for us as an industry to uplift the benefits of CDFIs and the impact that we have in various communities all across the country. I would like to believe that with the new administration, they would also see those benefits and how it helps to provide access to capital for marginalized communities.

BALYS: CDFIs have had strong bipartisan support for nearly our entire existence. For example, one tangible example is in the Senate, they created a Senate Community Development Finance Caucus [two] years ago. And it’s chaired by Sen. Warner, who’s a Democrat from Virginia, and Sen. Crapo, who’s a Republican from Idaho, so very different perspectives. The work of CDFIs bridges all of those gaps. That caucus is equally distributed, equally Republican and Democrat. And even after the election, one Republican is not returning and one Democrat’s not returning, so it’s still equally balanced. I believe we’ll have 24 members now. So that’s a quarter of the Senate have proactively signed up to be a member of this caucus supporting CDFIs.

We generally receive bipartisan support in the House as well. I do think CDFIs, along with pretty much every government program, are going to be moving into a much more restrained spending environment this year and next year and it’s been a trend since the end of the pandemic. Overall, there may be proposed cuts to the CDFI fund or to other programs CDFIs use in the same way that there are proposed cuts to a variety of parts of the federal government.

In the first Trump administration, in his budgets, he did propose several times to essentially zero out the CDFI fund or leave just a small amount in the fund for some administrative pieces. However, we were able to build a relationship with the administration. And I think in the pandemic in particular, members of his administration really saw the value of CDFIs in getting dollars out through the Paycheck Protection Program in particular. It was a way to reach those small businesses, rural businesses, minority owned businesses, all of those pots that the larger banks weren’t getting. I think some of it was just education and I do think that we made significant progress there so hopefully we’ll be able to build on that moving forward.

We still don’t have every race called on the House yet. We don’t know what that margin is going to look like, who might end up going into a position in the administration. So OFN is focusing on reaching out to our existing allies. There’s the largest Senate turnover in nearly a decade, I believe, so we’re doing a lot of education of new members. There’s about 60 or 70 new members of the House, too, I think. So it really is just sharing the message, the work that we’re doing and connecting members of Congress and other policymakers to those organizations that are already working in the community.

We’ve had the experience often of going and meeting with an elected official or policymaker, and they’re like, I don’t know what a CDFI is. And then we’ll mention an organization, one of our members, and they’ll say “Oh, I know them. I know the work that they do.” So it’s really just making that connection and demonstrating value.

Are there any ways that areas that are seeking to provide affordable, sustainable multifamily housing within communities that have significant income disparities—[such] that they kind of even out when shown geographically on eligibility maps—is there a way that opportunities can be extended to prove that that community is disadvantaged and impacted, even if it’s not shown in that map?

EGGER: That’s a great question. There are four or five different mechanisms that you can use to determine whether a property meets the EPA’s definition of LIDAC.Some are geography based. And some are actually project based. So, for instance, if there is an affordable housing project, regardless of its location, that qualifies. And that may meet exactly what you’re raising here in terms of saying a yes for that would be eligible.

Is there anything else to add about funding opportunities available for community-based organizations, working on increasing energy efficiency in historically disadvantaged communities?

BALYS: Erica talked about EPA’s requirements for who our sub-grantees can be and what those definitions are. But if you’re an organization doing work and you don’t meet that definition, I think there are a couple different ways. First of all, partner with an organization that does meet that definition.

I think the technical assistance funding that’s available, some of that both from OFN’s perspective and then potentially from our individual members, they may use some of that funding to contract out with another group to provide community outreach or to provide some piece that they need in order to implement their lending program.

A lot of these are going to have to go through a request for a proposal and a procurement process, so it will be a very public process if these come up. Those are the ones that come to my mind immediately.

EGGER: Yeah, I think that’s great, Mary Scott. And, you know, within NCIF, while the funding will not be directly provided to organizations, more provided to projects, we do anticipate that most of the projects that we’ll be financing are owned and managed by community-based organizations. Community-based organizations certainly can and should be, and we hope to be recipients of the market-building activities technical assistance. The actual financial assistance for NCIF at least will be going more directly to projects rather than providing general operating support for an organization.

KING: I was going to say exactly what Krista just said, the opportunity there, if those community organizations have projects. Krista, maybe share with those that have those projects what should they be doing right now to prepare for getting their projects considered, maybe through your application or other NCIF applications.

EGGER: Absolutely. One thing that could help is doing some kind of energy benchmarking for properties that you own or manage so that you can start to understand where across your portfolio—whether you have a portfolio of two buildings or 200 buildings—might have the most ripe opportunities for reducing emissions. As well as how your properties match up against those definitions of LIDAC through GGRF could be a great place to start.

Knowing where you are, how far you have to go to reach zero emissions, and what type of investment you could do along that pathway will help when all of the funding intake forms are open for everybody, for you to really understand what costs do you have? What gap in your capital stack? And what’s eligible for the funding that could be a good fit.

Because the government expects three coalitions to leverage these grants with private capital, and since that will come with return expectations and will pass through regional lenders before it will reach projects on the ground, how do the CDFIs and green banks plan to keep this capital affordable when it finally hits the ground at the project level, particularly in historically disinvested communities?

EGGER: It’s a great question. I mean, all of us have mentioned how historic this program is and yet we know that the need for capital to upgrade all buildings in the country is much higher even than GGRF is providing. And so that’s why it’s so important that these funds leverage private capital and other sources so that we can have an even greater impact.

Speaking for Power Forward Communities, given that we’re focusing on affordable housing and we know that oftentimes there are already many layers to the capital stack in affordable housing projects, the concept of leveraging private capital is certainly not a new one in this sector, and we’ll be leaning into that experience. We don’t expect from Power Forward’s perspective on the multifamily financial assistance side that our rates would be higher than 4 percent. So we are really trying to structure our capital, although it will be provided as a loan, to act as much like subsidy as we can, given that we know the constraints of community-based organizations to take on higher debt loads. I’m trying to structure the capital so that it’s easy to absorb and can fulfill the purpose of the program.

EGGER: We can’t wait to get started in January. We’re so looking forward to working with some of you.

Thanks so much, everybody.

Comments