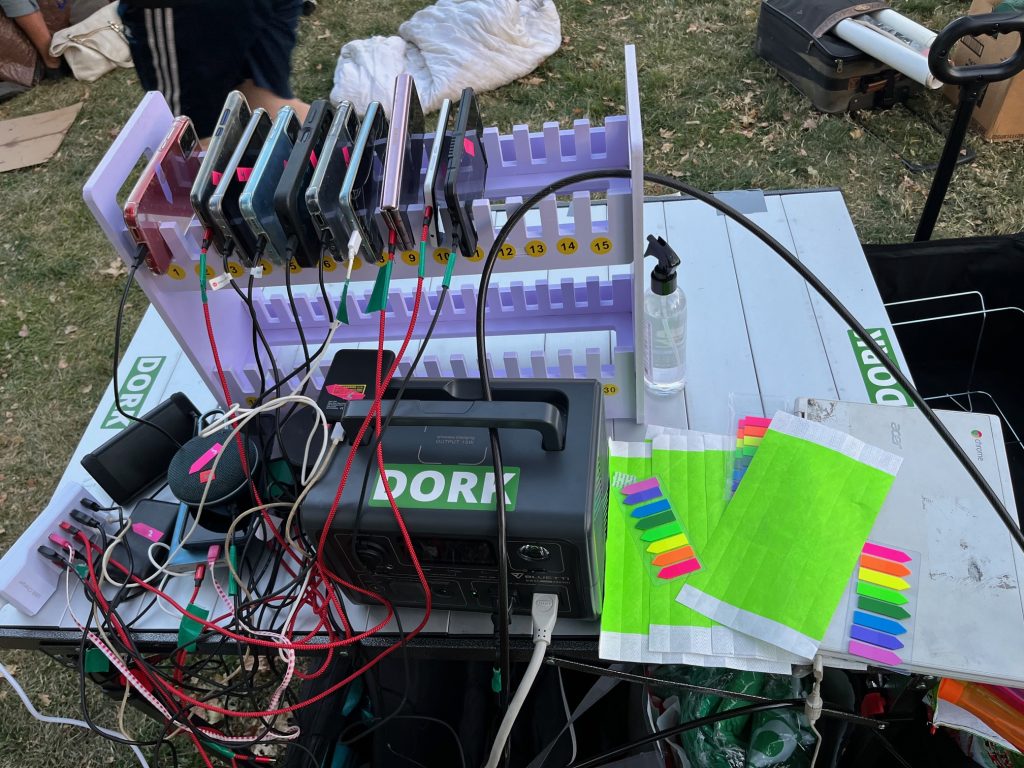

The cellphone charging station at Mutual Aid Monday, a weekly event for unhoused people in Denver. Photo by Susan Law

As the sun started to set one early October day in Denver, nearly 100 people gathered by the side of Denver’s City Hall for Mutual Aid Monday, a weekly event for unhoused people to get hot food, camping gear, haircuts, and clothes. People sprawled on the grass to eat and chat as ’90s R&B music played from speakers on a table labeled the “Dork Energy Station,” which included a portable cellphone charging station—the latest addition to the weekly outreach event.

“We are out here to raise awareness for a permanent fix,” says Susan Law, a 37-year-old lawyer and volunteer at the event. “People need their phones.”

The idea for the charging station had been sparked a few weeks prior by Law’s friend, Kevin Campbell, at a mental health awareness meet-up in a park, called Dork Dancing. “He said, you know, the music is great, but it would be even better if folks could charge up at the same time,” Law recalled. Now, volunteers have around 30 chargers for people to use during Mutual Aid Monday as part of their pilot program, and they hope to one day install permanent charging stations around the city.

Cellphones can be a lifeline for unhoused people to be able to access critical services, stay connected to support systems, remain up to date on current events, and find upward mobility. But locating outlets to charge them, especially throughout the pandemic, has been a challenge. Many also struggle to pay their monthly phone bill, and phones can easily be lost, broken, or stolen while living on the streets—which can set people back by making it more challenging for them to follow up with service providers or potential employers.

“People tend to be able to access cellphones,” says Benjamin Henwood, a professor at the University of Southern California who directs the Center for Homelessness, Housing and Health Equity Research. “The problem is keeping the phones active.”

It’s estimated that over half of unsheltered people own cell phones, according to research by Henwood and others. But turnover—meaning the phones were lost or stolen within three months—was high.

“Cellphones are ubiquitous and we all use them every day for anything and everything, including staying connected to people and also [finding] resources,” says Henwood, who is a trained clinical social worker. “That’s no different for our unsheltered population, and in some ways, even more pressing when you’re relying on transitory resources that don’t necessarily have a stable location.”

Windy Paskemin, 30, was at the Mutual Aid Monday event in hopes of getting a new phone charger. His last charger was stolen along with the rest of his belongings after he was taken to the hospital a week earlier. (Law says they hope to have extras to give out once they get more donations.)

Paskemin says he mainly uses his phone for entertainment, to listen to music, communicate with friends, and look up services. When he does have a charger, he charges his phone on the side of government buildings, at the library, or behind people’s homes. “You find what you can until you get kicked out, it’s just the way it goes,” Paskemin says.

Law says she often hears people say they charge their phones on the sides of private businesses or on people’s porches if they can’t afford a purchase at cafes and restaurants that restrict charging to paying customers. At the Dork Energy Station, she’ll charge anything—tablets, vapes, headlamps, even wheelchairs.

Kevin Campbell and Susan Law. Photo by Jess Wiederholt

Law says having a charged phone can help keep people safe. She’s spoken with women who were in crisis and couldn’t call for help because their phones weren’t charged. “Even just a little bit of a charge helps to ease people’s minds,” she says as she plugs in a man’s phone at the charging station.

“People have medical needs they need to attend to, and without a phone they can’t call their case worker,” she adds. “Keeping them charged is just really important.”

Keeping Cellphones Active and Navigating Inaccessible Systems

Albert Townsend, the director of Lived Experience and Innovation for the National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH), says once a person who is experiencing chronic homelessness gets a phone, it’s often hard for them to keep it long term because they’re focused on more urgent issues—like where their next meal will come from or where to find a safe place to sleep. Even for a person living in a homeless shelter, it’s difficult to access their own phone, he added.

“At one time, if multiple people lived at a shelter, the technology couldn’t be mailed to the shelter because the address would be the same for everybody,” he says, referring to a requirement from the federal Lifeline Assistance Program that only allows one user per household.

The program reduces the price of a phone and offers discounts for monthly plans for those who qualify. While eligibility requirements vary by state, generally a person must be enrolled in another government-funded program such as Medicaid or food assistance, or have a housing voucher in order to qualify for the program. A household is also eligible if the total household income is at or below 135 percent of the federal poverty guidelines for that state. (Here is a list of the providers in each state.)

Before working at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, Townsend was a homeless outreach case manager and relied on cellphones to stay in touch with clients. “As a case manager, you’re trying to figure out, are you going to be able to contact your client today?” he says. “And is their phone actually going to be on? If it’s not on, where could that client be?”

Even if they get a phone, many will struggle to pay their monthly phone bill, according to Cathy Alderman, the chief communications and public policy officer for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “It’s just another hoop they have to jump through,” she says.

Henwood says the pandemic highlighted how hard it can be for people to keep their phones charged, given that many coffee shops and businesses were locked down. He says the lack of access has created a black market for electricity access.

“There’s this whole underground network, where, I know in Skid Row, you can go into these places and for $2 charge your phone,” he says, referring to the neighborhood in LA that is home to one of largest homeless encampments in the country. “But a housed person might only pay 3 or 4 cents to charge their phone.

“So there is a huge markup premium for that, [and] that becomes a barrier or additional tax for people who don’t have a way to charge their phone.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: Crossing the Digital Divide During COVID]

Henwood says other homelessness researchers are exploring the possibility of using portable solar chargers or establishing charging stations similar to what Campbell and Law proposed. “I think there are people trying to figure this out, but it remains an issue,” Henwood says.

In addition to charging stations and cellphone access, Henwood would like to see access to homeless services be expanded using technology. “It’s not like you go in and there’s a kiosk where you can enter your information and request services, right? All of the information entered always goes through a homeless service provider,” he says.

If those systems were designed more with the “end user” in mind, they would allow people to have more autonomy and agency over what services they can access, he adds.

“These services can’t always be mediated through a service provider when there are shortages. Outreach doesn’t cover everybody who’s unsheltered. There’s a lot of issues there,” Henwood says.

One technology barrier some have run into is two-factor authentication, which requires a website user to provide multiple credentials for added security. Often, a code will be sent to the user’s phone to verify their information before they can access an email account or webpage. But if a person doesn’t have a phone, or can’t remember their email password, they can’t get their access code.

Though Henwood hasn’t run into this issue directly through his research, he could see it becoming more of a problem as the method becomes more widely used––and mandated.

Townsend says two-factor authentication is an example of homeless people being left out of the conversation when it comes to designing technology systems that are accessible.

“How do we make sure that our lived experience community can obtain technology in a way where it’s very useful and meaningful and purposeful?” he says. “Technology plays a very strong piece in really making sure that our voices are loud and clear.”

Using Technology to Connect Unhoused Residents with Resources

When Kevin Mendes came across a woman in a south LA park in late August, he did what he usually does—he introduced himself as an outreach worker and asked how he could help. Mendes works for Our Community LA, an organization that works to connect youth, families, and adults experiencing homelessness with free or low-cost services around Los Angeles County.

Her eyes lit up and she quickly told him in Spanish that she needed legal help for her daughter. He helped her hover her phone camera over the QR code on one of his flyers, which brought her to the WIN mobile app—a searchable database of nearby resources such as homeless shelters, crisis centers, food banks, and transportation programs. Together, they quickly found the nearest legal clinic on the app’s resource map and she hurried off.

“She was very thankful, and she asked for some flyers to give to others,” says Mendes, who has worked for the organization since July 2022. “You need a phone for pretty much everything now, especially the internet. I wish Wi-Fi was free everywhere.”

Henwood says cell phones can not only connect people with critical resources, they can also better connect researchers with people in order to come up with better solutions.

His research team conducts a monthly cellphone survey of LA’s unsheltered population to see how individuals’ health and living conditions change over time. An estimated 75,518 people experience homelessness on any given night in LA, according to the 2023 homeless count, and that number is considered an undercount.

The cellphone survey topics vary but have included questions about where they have been sleeping, any health issues they have, what services they use, and their experiences with discrimination, policing, violence, and victimization. The researchers send the link to the survey in a text message, with backup information sent to a person’s email. Participants receive a $10 electronic gift card.

The survey has helped dispel harmful stereotypes related to unhoused people, particularly the idea that unhoused people don’t want housing and would rather sleep outdoors. Early findings from the study showed that over 90 percent of people wanted permanent or temporary housing, versus 2 percent who said they would be interested in staying at a homeless shelter. Respondents cited lack of privacy, safety concerns, and negative interactions with staff as their top reasons for not staying at a homeless shelter.

Henwood says the survey collects information that is not captured in a typical homeless management information system.

“It’s helped us fill in some of the gaps,” he says.

He hopes that one day the Center for Homelessness, Housing and Health Equity Research can provide helpful information to participants through their phones, instead of just collecting information from them.

“The data suggests only maybe 15 percent of the population gets disability benefits, but at least half of our sample is indicating that they have serious functional impairment that may indicate that they are eligible or entitled,” Henwood says.

“We want to see if there is a way to connect people or let them know these things so that they can get what they’re entitled to.”

Comments