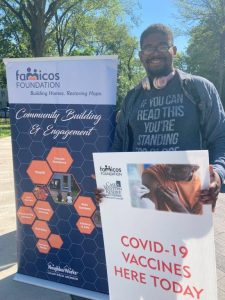

Famicos Foundation in Cleveland shifted to COVID-19 vaccination delivery in addition to its normal housing and social services. Photo courtesy of Famicos

In San Juan, Puerto Rico, the 14 staff members at Solo Por Hoy are well-versed in disaster response. Rocked by Hurricane Maria in September 2017, they saw the numbers of people experiencing homelessness shoot far above the population they were already seeking to connect to transitional and permanent housing. Then, earthquakes in early 2020 caused even more people to lack safe shelter.

And on the heels of that came COVID-19.

“The pandemic is not our first experience with disaster,” says Belinda Hill, Solo Por Hoy’s executive director. “We had a lot of practice.”

When the pandemic emerged in spring 2020, Solo Por Hoy pivoted quickly from offering housing and substance abuse prevention programs to also distributing masks and other COVID protections and teaming up with local providers to provide virus testing at pop-up mobile testing centers. Hill and her staff have facilitated more than 1,200 tests, on some days reaching 70 people at large central sites, on other days reaching maybe 10 or 15 people from a roaming vehicle, a provider partner administering tests from the front seat and Solo Por Hoy staff making housing referrals on the spot.

Over on the mainland, in Cleveland, the Famicos Foundation shifted to COVID-19 vaccination delivery in addition to its normal housing and social services. Tara Mowery, director of marketing, says vaccination efforts by the NeighborWorks-affiliated CDC take two forms: transporting elderly residents to outside vaccination sites, and bringing the vaccine to residents by arranging with health partners to administer shots onsite in its subsidized and permanently supportive housing buildings.

‘I had never seen the homeless population afraid. They are very resilient. But with COVID, they’re afraid of getting sick, afraid of dying—and they’re equally afraid to get the vaccine.’

In the short term, Famicos’ goal is a 75 percent vaccination rate, whether for a building or a neighborhood. “Right now we’re at about 30 percent—so we’re going to keep pushing,” says Mowery. “What does housing matter if there’s no one left to live in it?”

HUD, HHS Join Forces to Support COVID Efforts

Richard Cho, senior adviser for housing and services at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), says he’s not surprised agencies are facilitating vaccine support. As of Sept. 1, HUD field offices have facilitated the setup of more than 700 vaccine clinics in public housing sites or places where people experience homelessness.

“Particularly since the Biden administration began, we’ve wanted to make COVID response a whole-government effort, and we thought HUD had an important role to play,” Cho says. “People in HUD-assisted housing are more vulnerable for numerous reasons—they are older, the majority have some sort of underlying conditions, the housing conditions are more dense. Also, we serve people experiencing homelessness, who are highly vulnerable because of lack of access to housing or hygiene, or being in crowded shelters. So because of that, even though we are a housing agency, it was our responsibility to make sure people were protected from COVID-19.”

The federal pandemic response resulted in a deeper partnership between HUD and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a good sign for housing organizations scrambling to address COVID-19 in their communities. In a joint letter released April 30, HUD Secretary Marcia L. Fudge and HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra pledged collaboration in COVID-19 prevention and treatment and encouraged housing agencies and community health centers to expand and strengthen local partnerships.

In June, the two agencies issued a toolkit to support HUD-assisted housing organizations and health centers in crafting testing and vaccine delivery partnerships.

As with many pandemic-spurred solutions, Cho sees the dual-agency collaboration as something that should last beyond the crisis.

“We’re changing culture, making it clear that ensuring the health of people is certainly part of HUD’s mission,” he says. “While we’re doing this as a response to a pandemic, I hope we can continue and sustain and build upon this effort, so health care can be provided in and around people’s homes.”

Challenges, Goals, and Strategies

Solo Por Hoy in San Juan, Puerto Rico, has added COVID-19 testing and mask distributions to its usual services. Shown here is the Food-Box for Families, a collaborative effort, when Solo Por Hoy distributed 40,000 pounds of food to homeless families. Photo courtesy of Solo Por Hoy

For Solo Por Hoy, progress is often slowed by bottlenecks in funding as money passes through the island government, as well as by discrimination and indifference toward the homeless population in Puerto Rico, Hill says. Buffeted by fluctuations in funding, test supply, and provider availability, the testing effort paused in December 2020, ramped up again in March 2021, and continues today with 50 to 60 tests per week, as the homeless population still has not been widely vaccinated.

And then there’s the challenge of timing the COVID tests to match local shelter requirements.

“It took us a while to get the hang of it,” Hill says. “Homeless projects started not admitting people unless they were tested. We knew that on Fridays there are no admissions of new people to homeless housing. So to reduce barriers to housing, we had to do the tests on Tuesdays and Wednesdays and make referrals right away.”

Famicos, as a larger organization with some 50 staff and sufficient money on hand to spring into action even before grant funding arrived, had a relatively easy time pivoting, especially because it had strong health provider partnerships already in place.

“Even though we’re not a health organization, we’re literally down the block from the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western University and University Hospitals,” says Mowery. “We already had partnerships with them and with a couple of neighborhood clinics. So we were very quickly able to pivot and activate those partnerships.”

Beyond catalyzing shot delivery, Famicos is conducting an information campaign to combat vaccine hesitancy. It’s become clear that in the neighborhoods the agency serves, getting people to trust the vaccine—and those who administer it—requires on-the-ground direct communication. “It has to be one-on-one conversations, with someone you know,” Mowery says.

‘What does housing matter if there’s no one left to live in it?’

Clearly, this pandemic year-and-a-half has been exhausting for people on the front lines. For Hill, the worst part about COVID has been seeing homeless people truly in fear, something she commented on to local media back in spring 2020 and reiterated recently.

“I had never seen the homeless population afraid. They are very resilient. But with COVID, they’re afraid of getting sick, afraid of dying—and they’re equally afraid to get the vaccine,” she says. “The resistance may be hard to comprehend, but our job is not to judge.”

‘A No-Brainer’ for Housing Organizations

Despite learning curves and logistical and emotional strain, neither Hill nor Mowery expresses a shred of hesitancy about adding unfamiliar health services to their already-full slate.

“I look at everything as an opportunity and a lesson. What are we going to learn here? How are we going to get this done?” Hill says. “The crisis doesn’t change a homeless person’s situation. Our job is to continue providing services despite disasters. The good news is I have a wonderful team, very committed, and they take on the challenges with me.”

For Famicos, it was a “no-brainer” to shift to vaccine delivery, Mowery says. “We still have to go into Mrs. Johnson’s apartment and fix a leaky faucet. The last thing we want to do is go in to fix a faucet and leave someone with COVID.”

CDCs ‘Thinking Outside the Box’ and Looking Ahead

On the positive side, Mowery says, the COVID crisis has pushed organizations to be more open and creative in responding to problems.

“Thinking outside the box—we need to continue with that,” she says.

One of the things Famicos is investigating—and that Mowery expects will be a trend in the community development world—is bringing community health workers into the mix. These workers could be on staff with a housing organization or employed by a health institution but assigned to the community as an “umbrella” person overseeing health issues communitywide.

“The community health worker would be a point person who has medical knowledge and is literally in the community talking to people, answering medical questions, and arranging things like health screenings onsite in housing or at farmers’ markets or back-to-school events,” says Mowery.

And now that housing organizations have dipped into testing and vaccination, why not go further and consider facilitating more medical services?

“This vaccine effort is the first time we’ve jumped into such a medical focus,” Mowery says. “There are other things, like mammograms, that a CDC wouldn’t normally deal with. But we have the power, because we have partnerships, to ask our partners to come and do that onsite. There’s no reason we can’t combine medical screenings or a vaccine clinic with a food distribution event we’re already doing.”

She adds, “So how do we make these things more organically connected, and not in separate quadrants? A community health worker could help with that.”

Longstanding health inequities will persist long after COVID, but Mowery hopes that building trust can save lives now while building a stronger foundation for long-term health.

“If we can break down vaccine hesitancy now, that could pave the road for later vaccinations, flu shots, making sure babies are getting their shots,” says Mowery. “COVID is a catalyst forcing us to think outside the box, to pivot, to explore our partnerships in different ways. But it’s not the end, because there are going to be different health issues down the road.”

Comments