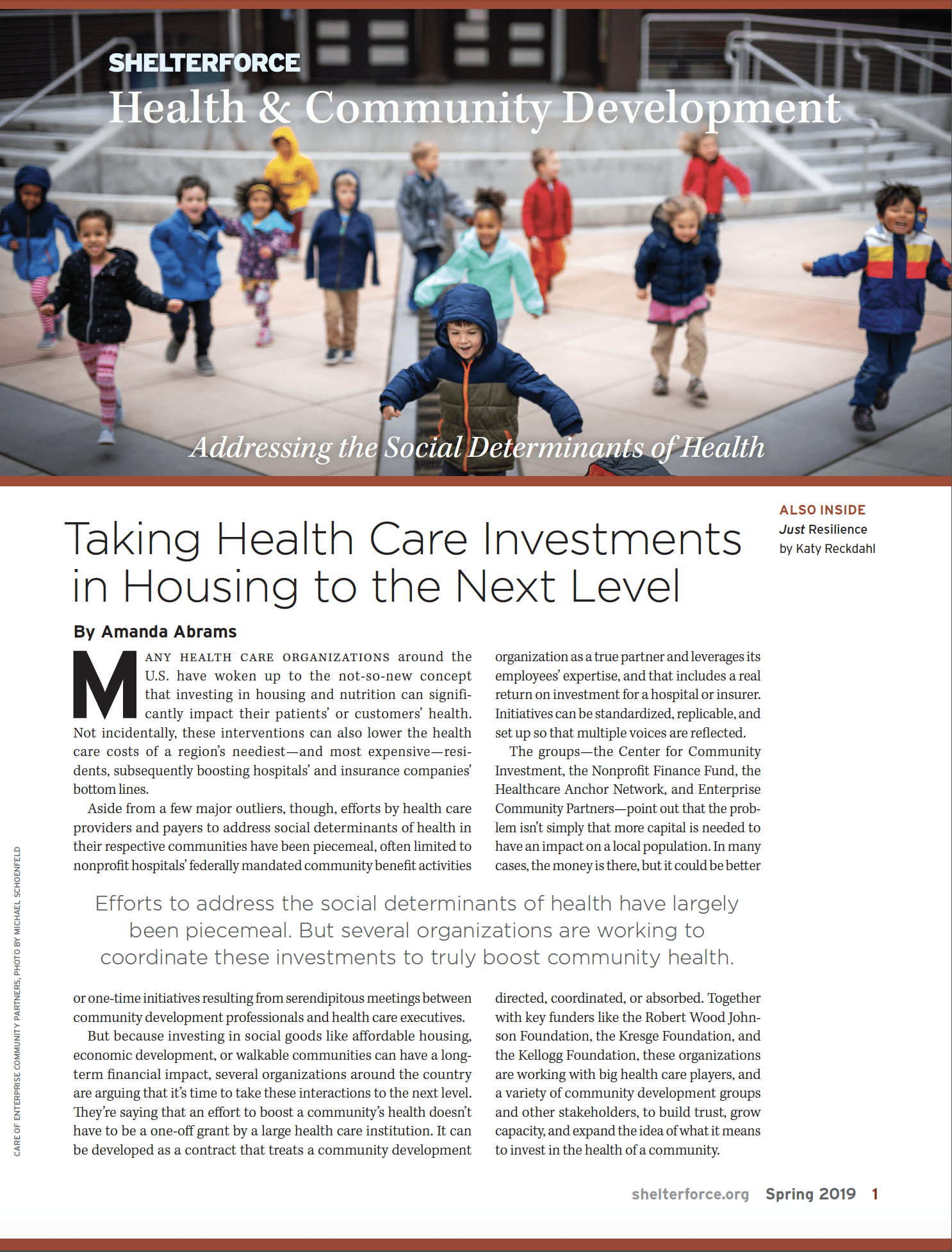

The Florida Keys Community Land Trust on Big Pine Key was created in response to Hurricane Irma bashing the area. Big Pine Keys was where most of the catastrophic damage occurred in the island chain. More than 700 buildings, mostly homes, were destroyed or severely damaged. Photo by Jenni Konrad via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

When the earliest community land trusts (CLT) were created in the early 1970s, it was based on the communitarian notion that while people might have a right to own their homes, land should not be for sale because it belongs to the community.

Over the years, CLTs have helped low-income families become homeowners by allowing them to lease the land under their homes rather than buy it. Today, with the intensification of weather patterns resulting from climate change, CLTs have taken on new roles. When hurricanes and/or other natural disasters strike, the CLT—a nonprofit corporation—performs vital functions that help people recover.

Here are the stories of three such CLTs.

San Juan, Puerto Rico

The Caño Martín Peña CLT in San Juan, Puerto Rico, which was created in 2004 by the Puerto Rican legislature after two years of community organizing, was established for the benefit of depressed communities surrounding the Martín Peña Channel, a highly polluted waterway running through central San Juan. These communities are home to approximately 25,000 people, although the exact number is hard to pin down because after Hurricane Maria in October 2017, many residents left for the U.S. mainland permanently, while others go back and forth. “People have lived on this land for 80 years,” says Maria Hernandez, board president of the Caño Martín Peña CLT. Of the eight communities along the channel, seven are part of the land trust.

Every time there is heavy rain, the community is flooded with contaminated water because of the toxic condition of Martín Peña channel, an old canal that runs through the neighborhoods. The federal government has plans to dredge and clean the channel, but before the work can begin, many residents will have to relocate, at least temporarily. Thus far, roughly half of the 1,500 families who live in the area have left, while many more will need to do so. A committee made up of mostly residents is helping neighbors find adequate accommodations, says Hernandez.

“The fabric of the community doesn’t have to be broken,” says Hernandez, referring to the temporary displacement of residents. Some families can even stay with their neighbors, she adds.

If the CLT residents did not have the land trust to depend on, leaving their homes, even temporarily, could subject them to a land grab by developers who are eager to turn their waterfront neighborhoods into luxury resorts once the dredging is complete. But today, CLT residents though they may not own their land, do have surface rights, which give them the legal right to live in and return to their homes.

The regulations and infrastructure were in place for the CLT by 2008. However, there were political challenges with a change of leadership in 2009, when the ruling party took back land deeded to the CLT just a month before, so the CLT was not able to begin its work in earnest until 2014.

While it is clear that the CLT is of great importance during normal times, the real test of the value of the CLT in San Juan came after Hurricane Maria. “The biggest problem after Maria was distribution,” says John E. Davis, longtime community land trust advocate and partner at Vermont-based Burlington Associates in Community Development.

“Even when FEMA airlifted pallets of water to San Juan, they sat on the runway. But at Caño Martín Peña, volunteers went out and distributed the water. The work crews cleared the streets, picked up tarps, and advocates [lawyers and notaries] helped residents apply for aid,” says Davis.

Some of these same volunteers also “helped people get loans from FEMA, prevent foreclosure of their homes and put permanent roofs on houses after the storm,” he says.

The volunteers at Caño Martín Peña also cleaned houses that were flooded and overrun with toxic debris, and brought in medical personnel, generators, and solar lamps, Hernandez says.

The establishment of a land trust is important for a community that lives in extreme poverty. But the trust does not operate on its own. When the Puerto Rican legislature created the community land trust it also created the ENLACE Project Corporation, the latter having the advantage of being able to receive money from the Puerto Rican government to benefit the inhabitants of the Caño Martín Peña neighborhoods.

If there was any silver lining in the cloud that rained down on Caño Martín Peña in 2017, it was that Puerto Rico has been promised $20 billion for storm recovery, which may be small comfort given the enormous damage done on the island. But Hernandez hopes that at least some of the money can be used to pay for the $200 million dredging and clean-up project on the channel.

One thing is for sure, says Hernandez. “Because of [the CLT and ENLACE] which have organized the people living in the Caño Martín Peña neighborhoods, they have a newfound respect. In the past, these residents were ignored by government agencies.”

The Florida Keys

The existence of the Caño Martín Peña Community Land Trust was crucial to many residents when Hurricane Maria hit. The Florida Keys Community Land Trust on Big Pine Key on the other hand was formed in December 2017, in response to Hurricane Irma bashing the area. Big Pine Key was where most of the catastrophic damage occurred in the island chain, says Mike Laurent, the land trust’s executive director since March 2018. According to the Monroe County Building Department, 772 buildings, mostly homes, were destroyed or severely damaged by the storm on Big Pine Key.

Though the land trust focused on Big Pine Key because of the extensive damage it sustained, “We are not limiting ourselves to this island, and, in fact, we are also having discussions with property owners in Key West, which is 26 to 30 miles away,” says Laurent.

A Florida Panhandle native, Laurent came to the Keys from Atlanta, where he was living at the time of the storm, because of his friendship with Maggie Whitcomb and her husband, Richard. The couple donated more than $2 million to buy land for the CLT. Maggie Whitcomb is the founder of the trust, while her husband is a supporter who does not have a management role at the nonprofit. It is unusual for a CLT to be founded by an individual.

According to Laurent, affordable housing dominated Big Pine Key, and much of it was directly affected by Irma. “Older homes that were destroyed couldn’t be built back because it would be too expensive . . . You’d have to mitigate the hazards and build to current code.”

Most people in the Keys did not have insurance, says Laurent; those who were insured had, at best, insufficient coverage. It is hard to insure a home in the Keys because the extreme risk from flooding and wind damage makes insurance extremely expensive.

Every lot bought by the trust was a site where Irma had destroyed a home, says Laurent. As a result, “Very early on, there was a lot of speculation about whether the land trust was legitimate, or a simple land grab . . . After all, there is always a lot of speculative buying in situations like these, which drives up land prices.” But those suspicions faded away over time, he says, especially after people saw that a 99-year deed restriction on the land requires that it be used only for affordable housing.

People were also suspicious, initially, of outsiders coming in to help with the recovery, says Laurent. “Monroe County has a strong feeling of pride about being a ‘Conch,’” the colloquial name for natives of the Keys.

The Whitcombs, who, like Laurent, are from Atlanta, were only part-time residents in the Keys, but over the last year or so, they began to earn the trust of full-time Keys residents.

George Neugent, former Monroe County Commissioner, says not only did Whitcomb and her husband have the discretionary funds, “but the heart to step up and rebuild houses destroyed by Hurricane Irma.” Plus, it helped that many people sold their properties and left the Keys after the storm, he says. Although there were a many lots available for purchase, the value of the land did not decrease because there was still a desire to live and/or vacation in the Keys.

A number of nonprofit groups also contributed to the land trust and the rebuilding process. In the year and a half after Irma, the Ocean Reef Community Foundation contributed almost $89,000 to the CLT and the Florida Keys Hurricane Recovery Foundation contributed $46,500. But the entity that contributed the biggest dollar amount was Monroe County, which purchased four lots initially bought by the trust. As of February 2019, the trust owns nine lots. There are 11 additional lots—currently owned by a holding company—available to the trust when it’s ready to develop them.

Besides the funding sources listed above, disaster funding is coming from Rebuild Florida, which is a partnership between the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In the first phase of Rebuild Florida, $50 million has been earmarked for the repair and rebuilding of low-to-moderate income housing in Monroe County. The deadline for homeowners to register for Rebuild Florida is March 29, 2019.

Irma exacerbated what was already a housing shortage in the Keys. Today, some workers, including construction workers, are commuting from as far away as Homestead, a three-hour drive each way, says Laurent. Other not-so-appealing alternatives for living space include sharing a house. One man, who works as a server at a Marriott in the Keys, pays over $550 a month to live in a home with 11 other people, says Laurent.

“Our mission at the land trust is to build not just affordable workforce housing, but housing that will be resilient,” says Laurent. The windows and the roofs of the first four homes are hurricane resistant for winds of up to 200 miles per hour, which is a commercial grade, he says. However, the land trust may not be able to continue with that standard because of the cost and the difficulty of getting the windows in a timely manner. The current county code requires wind resistance up to 180 miles per hour.

The building code became stricter in the years after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which hit Homestead, Florida, particularly hard. In the Keys, owing to the serious threat of storm surge and the narrow escape route leading out of the islands—only one road exists to carry all of its residents to safety when a storm is threatened—in many places, buildings must be elevated anywhere from 3 to 12 feet off the ground, depending on what FEMA maps dictate.

Besides the cost of land and the strict building codes, the cost of building materials and labor is “going through the roof,” says Laurent. “My guess is that the cost to build a hurricane-proof building has gone up about 20 percent just in the last two years.” Tariffs on Canadian lumber contribute to increased costs. But in spite of the difficulties and the expense, as of early December 2018 the community land trust had completed its first two homes, with the other two expected to be finished by the end of January 2019.

“We plan, for our first two phases, to build a total of nine homes. Our goal is to build between 20 and 30 houses in the first two and a half years,” Laurent says.

Members of the Monroe County workforce will be first in line when tenants are chosen. Tourist industry workers, firefighters, police officers, teachers, and construction industry workers are in this category. If workers were displaced temporarily by Irma, and they can prove that they had been earning 70 percent of their income in the county, they will also be considered, Laurent says.

But as carefully as the land trust might screen prospective tenants, anyone with property in the Keys—from Key West to Key Largo—knows that there are opportunities to rent these new homes as vacation rentals, rather than to a police officer or a teacher, says Laurent.

While the CLT will carefully choose who signs leases, it will be hard to prevent tenants from subleasing these homes—even though it will be illegal to do so—to vacationers, who will offer them a lot of money, says Laurent. If this happens, the practice will suppress the rental supply for workers, he says.

Rents in the Keys’ CLT are going to be based on Monroe County’s average median income. For the first four homes, the maximum rent will be $1,588 and renters will be qualified by income. These units will have 760 square feet of living space, including two bedrooms. “Initially we are only building to rent, because the rental stock in Monroe County is very low right now, but at some point, we will want to sell the homes,” says Laurent.

Liberty City, Miami

If the ocean is both a bane and a blessing for residents of the Florida Keys, increased (vertical) distance from the ocean is what attracts investors to the land chosen by SMASH (Struggle for Miami’s Affordable and Sustainable Housing), a fledgling Miami-based community land trust. The impetus for creating this CLT was climate gentrification, which is not much different from ordinary gentrification, except that it is characterized by developers turning to distressed neighborhoods not just because “greenfields” are disappearing and they want to find new profit centers. In Miami, as in other cities facing risk from sea level rise, developers are in search of higher ground. It’s found inland rather than along the ocean or the Intracoastal Waterway, the traditional places to build luxury development.

SMASH’s work began with the impoverished northwest Miami neighborhood of Liberty City, where the organization has chosen a quarter-acre lot as the site of its first development. The lot, filled with overgrown weeds, does not look very appealing today, but it has attracted the interest of for-profit developers and investors because of its elevation. It’s 15 feet above sea level, the Miami equivalent of Mount Kilimanjaro. The average elevation in Miami is 4.4 feet and some parts of the city and its suburbs are at sea level.

SMASH hosts an educational workshop about community land trusts and tenant rights. Photo courtesy of SMASH

Usually affordable housing is built on public land, says Adrian Madriz, executive director for SMASH. “But you have to have a track record to become an affordable housing developer. If you don’t, you need money to get experience,” he says. To get around this problem, SMASH found a landowner, in this case one who is also a general contractor, who was looking for a developer and open to an unusual offer.

SMASH convinced the owner to sign a six-month contract on Aug. 2, 2018, which gave the organization control over the site before payment was to be made. But on Dec. 19, SMASH signed an extension agreement with a new deadline of July 29, 2019, by which time it expects to break ground.

During the contract period, SMASH has to find $10,000 (the below-market purchase price) and present the seller with a design plan; the latter has already been done. Plus, SMASH has pledged to pay $300,000 in liens on the property assessed by Miami-Dade County—$275,000 in fines for not cutting the grass for 15 years, and $25,000 in taxes. However, the county will waive the liens as long as the buyer does affordable housing, says Madriz. The taxes can’t be waived because the tax certificates have already been sold, he says.

As for the development itself, the “SMASH Housing Project” will be a mixed-income property that will have only three apartments because the site is small and the project—estimated to cost $325,000—will be considered a pilot that, hopefully, will be replicated later on, says Madriz.

The plan for the SMASH development includes one apartment that will be set aside for people who earn 30 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI). That apartment will rent for $300 per month and will include two bedrooms and one bath. The development will also include one transitional housing unit for LGBTQ homeless youth that will have two bedrooms and one bathroom and rent for $1,200 per month. The occupants will be four adolescents and/or young adults and the rent will be paid by Education Tomorrow, a nonprofit organization that mentors at-risk youth.

A third unit will be market-rate, have three bedrooms and two baths, and will rent for $1,600. This development is designed to show that mixed-income/community land trust housing will work in Miami-Dade County, says Madriz.

The quality of construction will be high and it will be resilient, says Madriz. “We are looking at solar panels, windmill technology, and composting. There are private services that pick up compost to turn [it] into soil,” he says.

SMASH is also looking for ways to cut costs, including finding sources of donated materials. There are lots of foundations, such as the Lowe’s Community Partners grants program, says Madriz, that donate wood, tools, and other building supplies.

Plus, SMASH is looking into new technologies that will help keep costs down. For example, says Madriz, there have been lots of advances in pre-fab technology, which is more cost-effective than conventional construction.

In most community land trust housing, residents aspire to become homeowners, but this will not be the case for this development because of some of the residents’ low incomes, according to Madriz. The best way to develop housing for people with very low incomes is through the community land trust model rather than through for-profit affordable housing developers, who try to avoid building for occupants with only 30 percent of AMI, says Madriz.

SMASH plans to rely on three sources of funding to develop the land in Liberty City. As of early January, it had applied for a Miami-Dade County Economic Development Grant. It will apply for a loan from a nonprofit lender such as the Florida Community Loan Fund and it will use the proceeds from a recent crowdfunding campaign that raised $325,140 in cash and pledges.

“The reason we decided to do a crowd-funding campaign,” says Madriz, “is that we want (the development) to be owned by the community, instead of just rich people making the decisions.”

Madriz says he is confident that SMASH will have success with its first development, because of the wealth of experience of the organization’s board members, who include Aaron McKinney, an assistant project manager for Related Urban, an affordable housing developer with ties to The Related Group; Lennox Griffith, the former project manager for the Miami-Dade County Housing Authority; and Kevin Wilkins, founder and managing director of trepwise LLC, a management consultant firm based in New Orleans that has guided many for-profit and nonprofit enterprises.

SMASH will also partner with other nonprofits, such as a resource center for LGBTQ youth called Prideline; Educate Tomorrow; and Care Resource, a combination medical clinic and psychological counseling center. “These organizations already offer programs for the community, but our development will serve as an access point,” says Madriz.

Although each of the CLTs described in this story is unique, they all have similar goals. In addition to providing low-income housing, they also strive to promote social cohesion and alleviate poverty while aspiring to protect residents from the hazards of climate change.

This is a very inspirational story about how CLTs can address the extreme weather episodes cause by climate change. We have done a study in the Bay Area about about how housing cooperatives, especially those linked with CLTs, can be a positive planning tool for mitigating the effects of climate change. Many CLTs focus on single family homes, but we use the co-op model as a way to use denser development and share resources to allow the benefits of resident controlled housing. We produced a report (https://bayareaclt.org/programs/green_living.php) that highlight the kinds of projects that co-ops in our area have undertaken, including community gardens, solar panels, shared vehicles, rain water catchment, and many other elements that be done more easily when you live in a co-op community.