‘Styven Magnes : Speech balloons’ by Mark Wathieu, via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

Public housing, tax increment financing, inclusionary zoning—these are all terms that may be known to people working every day in community development, but to the general public they are little more than obscure echoes of bureaucracy. At times, we may forget the complexity of our work and then wonder why the “Not in My Backyard” knee-jerk response dominates so much of neighborhood discourse around community development.

Efforts to change this atmosphere are needed, and they may be assisted by the work of artists.

Face It was a temporary public art installation produced by archi-treasures, an arts-based community development nonprofit in Chicago. It was also its first partnership with Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation, a community development organization that is focused on Chicago’s north west side. Bickerdike was open to supporting a project that was intentionally temporary and youth-driven, allowing the concept to develop from the ground up. It trusted the archi-treasures artists and youth to come up with something from, and for, the neighborhood.

A team of artists began working with Bickerdike’s Youth Council—a previously established group—to develop an art project inspired by the upcoming development of 12 new affordable, single-family homes, and three 2-flats as part of the city’s New Homes for Chicago program. Members of the youth council had been chosen for their experiences as affordable housing residents in the community.

[RELATED: Exploring Foreclosure Through Art]

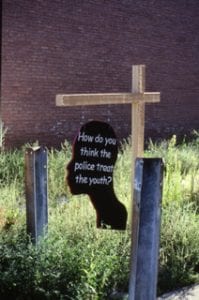

The project began with workshops focused on opening a community discussion about housing by encouraging young people to speak about their own experiences as residents. The artists then worked with them to develop a survey that the teens took door-to-door to neighbors, whose responses were audio recorded. The group distilled those responses, along with messages from workshop conversations about housing, gentrification, and life in the neighborhood, and put them on temporary hanging signs in the shape of participants’ silhouettes. The signs were installed on each of the 13 planned development lots.

Photo courtesy of Joyce Fernandes

The young people working on the project varied in age, but a core group of teenagers considered themselves graffiti artists. Artist Michael Piazza focused their interests by designing the signs so one side displayed text, and the flip side was a graffiti interpretation of the same text designed by the young artists.

The signs that appeared on the lots around Humboldt Park were subtle yet provocative. One sign displayed a child’s drawing of a house with the handwritten words, “I would want a house like this” below. Another, “We may not be rich but . . . ” expressed the stigma that can burden many children who live in subsidized housing. Tensions with police in the neighborhood were also expressed in a sign that asked, “How do you think the police treat youth?”

Photo courtesy of Joyce Fernandes

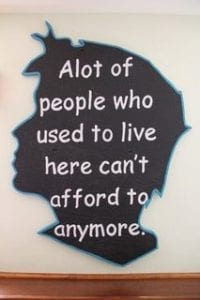

Issues surrounding gentrification and neighborhood change are often raised when new construction takes place in a neighborhood. One Face It sign stated simply, “A lot of people who used to live here can’t afford to anymore.”

As the signs were installed, they prompted one-on-one conversations with neighbors that revealed a widespread lack of understanding about the development. Also, many folks conflated the concept of affordable housing with deeply embedded and sometimes traumatic ideas about Chicago’s high-rise housing projects.

As construction progressed, Face It signs were removed to make way for construction of new homes that people from the neighborhood could afford to own. Taken together, the messages produced in this temporary public art installation provided an investigation into a divisive issue—the need for affordable housing in historically poor and disenfranchised neighborhoods undergoing change. Rather than the aggressive and often racist objections that are typical of community meetings in which subsidized housing projects are proposed, Face It provided moments for critical reflection for residents of the neighborhood itself.

Photo courtesy of Joyce Fernandes

Face It was an unusual partnership between arts practitioners and a housing organization that helped to shift the narrative about artists, community development, and affordable housing in Humboldt Park. Art, especially public art, provides a space for perception and thought, unhindered by the burden of instantaneous response and conflict. This is a space marked by exchange and learning on the part of both the artists who worked on the project and those who were witness to it.

At a time when the conversation around artists and gentrification is fraught with blame and retaliation, the right collaborations can design creative responses that instead contribute to discussions—and attempt to find answers.

Comments