An open house protest outsid Pigeon Palace on May 5, 2015. Photo courtesy of Chris Carlsson

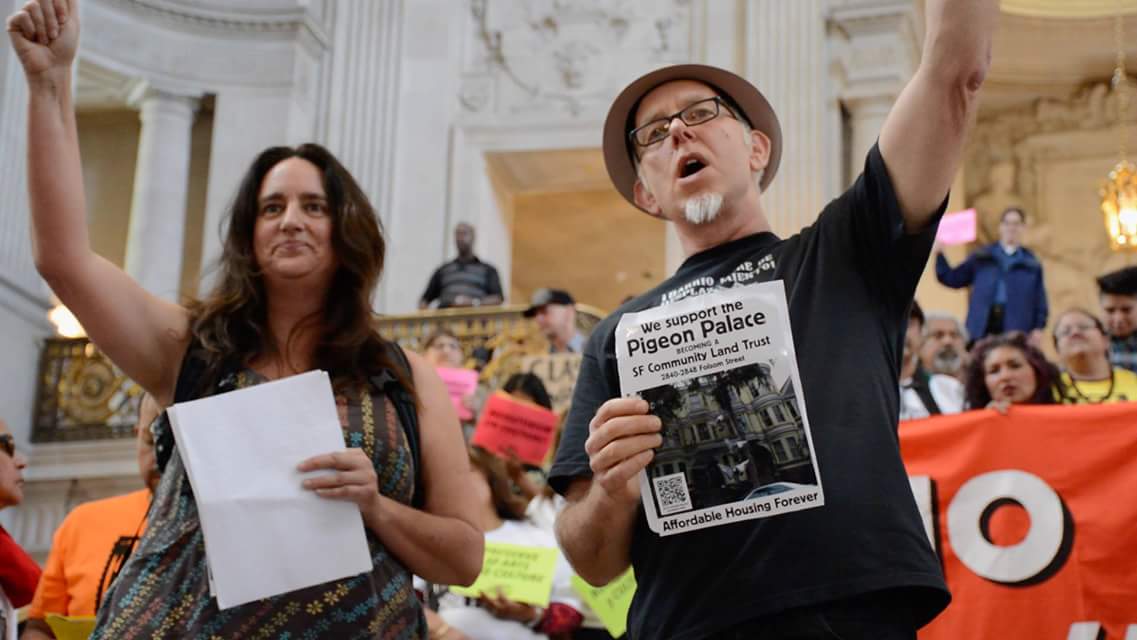

Carin McKay and Chris Carlsson at City Hall during a Mission No Eviction protest in 2015. Photo by Steve Rhodes

As a resident of the Pigeon Palace in San Francisco, I am enjoying the peace of mind that comes from knowing that I will never be evicted from my home. I’ve been happily surprised to feel a subtle shift in my experience of daily life. I hadn’t realized how much I was preparing to leave until I was certain that I wouldn’t be forced out. I’m here for the long haul, and with that comes both possibilities and responsibilities.

In 2015, speculative real estate vultures were hungrily circling our century-old, six-unit Victorian on Folsom Street in the heart of the Mission. To save our homes, we established a low-income, nonprofit housing co-op called Pigeon Palace Inc. The San Francisco Community Land Trust (SFCLT), our political and economic partner (and benefactor), won a probate auction, outlasting and outbidding one of the worst serial evictors in town to purchase the property for us. The deal was completed with loans from a private bank, the Mayor’s Office of Housing “Small Sites Program,” and private investors (including the tenants and our friends). With this purchase, we have taken the building off the market forever. Thousands of San Franciscans supported us and many are inspired by our story and excited to know at least one less building of friends was lost to the steamroller of gentrification.

But stabilizing our home came at a steep price. Competing in the market to make the purchase has saddled us with nearly $4 million in debt, a reality that casts a pall over our project and makes this a difficult model for widespread adoption or replication. Our story, while inspiring on the face of it, sadly represents many of the worst contradictions that dominate the politics of housing, not just in San Francisco but in every desirable city in the world.

The open probate auction should have never happened. Local authorities allowed a building that last changed hands in 1946 for $12,000 (yes twelve thousand dollars!) to be put into an open auction that drove the price from the original listing of $1.5 million to nearly $3.3 million. To save our homes, Pigeon Palace was purchased at the height of the market for an absurdly high price. The widely accepted logic of our culture is that this so-called “market price” was fair and to have sold the building for less would have been a disservice to our former landlady, the ostensible “beneficiary” of this largesse.

Our story is unfinished and a real fight still looms. We no longer face the threat of possible eviction by speculators. We now confront the well-disguised iron hand of the market wrapped in the velvet gloves of “affordability” and “fairness,” pitting us against efforts by our public financiers to force us into higher rents over time. After a number of delays, the Mayor’s Office of Housing only authorized their loan to us subject to burdensome conditions that, given the limited sources of financing available for housing preservation, we were forced to agree to.

It is a “soft second” mortgage of $2.6 million, which means we don’t even have to start paying it for a generation. That makes it a generous deal in real, immediate terms. But our stated goal is to convert the building from a SFCLT-owned rental property into a co-op with a 99-year lease for the shareholders, which is equivalent to ownership under California law. We are committed to a self-managed co-op model (which we are largely living already), based on the future conversion of the building, which was originally scheduled to take place five to seven years after the initial purchase. We learned the hard way, however, that the mayor’s office is hostile to the model of self-managed co-ops run by the residents. In our case, we were treated as though our ostensible poverty rendered us incapable of responsibly managing our own homes.

Inserted into our loan papers is an agreement that when and if we ever convert to co-op, we would recalculate our monthly rents to be a MINIMUM of one-third of our gross income! First of all, where does the one-third of gross income come from? It can be traced back to Depression-era New Deal politics when calculations about how impoverished Americans used their limited incomes concluded that no one could possibly afford to pay more than 25 percent of their monthly income for housing. Over the years, this ceiling on housing costs for poor people floated up toward 30 percent, which has been used by HUD bureaucrats to calculate how much a housing choice voucher should be subsidized. For Pigeon Palace, the unelected staffers at the Mayor’s Office of Housing arbitrarily raised that number to 33 percent and instead of using it as a ceiling, they established it as a floor in our loan papers!

This bureaucratic sleight of hand was justified to me in various meetings and informal discussions as being “only fair.” Fair to whom we might ask? Does the fact that so many San Franciscans have been forced into paying 50 percent or more of their income for housing mean that everyone must be gouged? I lived for many years paying closer to 10 to 15 percent of my income for housing. Why should I pay 33 percent now? That’s only fair if you assume that it is reasonable and fair that banks and corporations who dominate property ownership (with the small property owners as their vociferous public face) have a right to an ever-increasing proportion of social wealth.

The city, in providing the $2.6 million “second” loan, actually bought control of the building and set the terms of its finances. The most immediate result was to unnecessarily increase the rent on the two empty units to more than double the other rents. While the city’s logic is to create “mixed-income housing” to support the long-term finances of the building, for residents, these increases disrupt the economic promise of the building and create an unfair class hierarchy among a small number of residents. If the building can support lower rents, why would we increase them just to meet this “mixed income” standard? These city employees are defending the demands of banks, real estate agents, lawyers, and developers at the expense of the city’s lower-income workers, including service workers, teachers, activists, artists, and nonprofit service providers.

Our building has had cheap rents and it is precisely these cheap rents that gave the tenants the safe and stable foundation that allowed us all to contribute so much to San Francisco’s cultural and political life for the past several decades. A low cost of housing is an essential foundation for a full life. Moreover, low-cost housing is an indispensable ingredient that makes possible a dynamic, artistic, multiethnic, class-diverse culture to thrive.

The owning class has turned to property and rents as its primary mechanism to concentrate wealth and power. As we resist higher housing prices, we fight for individual freedom from the dictatorship of neoliberal, profit-driven economic reasoning. Just as importantly, we also defend the ability of cultures to develop and thrive in times and spaces not subjected to generating ever more money to pay landlords and banks for the homes that should be our human right.

Comments